Shock and Awe by Simon Reynolds, Dey Street Books, 2016

I don’t really understand the concept of comfort food. Nothing that requires a trip to the supermarket and/or actual cooking could provide me with any real comfort. However, I do have some sense of what it might mean in terms of a musical diet. I’m not talking about ‘guilty pleasures’ here. I never feel guilty about the music I like. This is macaroni and cheese music, reliable old stuff that doesn’t challenge but does satisfy. It might not change your life but it reminds you of just how good it can be.

I don’t really understand the concept of comfort food. Nothing that requires a trip to the supermarket and/or actual cooking could provide me with any real comfort. However, I do have some sense of what it might mean in terms of a musical diet. I’m not talking about ‘guilty pleasures’ here. I never feel guilty about the music I like. This is macaroni and cheese music, reliable old stuff that doesn’t challenge but does satisfy. It might not change your life but it reminds you of just how good it can be.

For me, Glam is comfort music. There is no more reliable record in my collection than The Slider by T Rex. It’s not my favourite album by any stretch and I wouldn’t even call myself a huge fan of the band. But when I’ve had a bad day, there’s nothing like that opening riff to Metal Guru. I’m slightly too young to recall glam as such but I was around for it. Maybe it was on in the background, maybe it was Suzi Quatro on Happy Days. I’m not sure but I feel as though it represents something fundamental to me as far as rock and roll goes. I was, thus, very keen to read Simon Reynolds’ new book on the matter, Shock and Awe.

This is, arguably, the first major study of the genre. There are other books on the subject. Philip Auslander’s Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Pop Music is a thoughtful take on it and Dandies in the Underworld by Alwyn Turner is an informative, if brief, account too. However, the Simon Reynolds treatment is of another order altogether. He has previously written on hip hop, nostalgia, post punk, and rave. He is not simply a fan with flare. All of his work mixes critical theory with extensive research. This isn’t rock and roll, this is serious!

This is, arguably, the first major study of the genre. There are other books on the subject. Philip Auslander’s Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Pop Music is a thoughtful take on it and Dandies in the Underworld by Alwyn Turner is an informative, if brief, account too. However, the Simon Reynolds treatment is of another order altogether. He has previously written on hip hop, nostalgia, post punk, and rave. He is not simply a fan with flare. All of his work mixes critical theory with extensive research. This isn’t rock and roll, this is serious!

He begins with Marc Bolan, the dreamy ex Mod whose reinvention as an acoustic Syd Barrett in Tyrannosaurus Rex is one starting point for the glam genre. Another is Beau Brummel, the Regency clothes horse who shined his shoes with champagne. There is also Oscar Wilde whose paradoxical (were they?) pronouncements on superficiality read like a mission statement for the period.

Reynolds also looks into the etymology of the term ‘glam’ which is, of course, short for glamour. The word was originally associated with magic and the occult. David Bowie fans will know that Aleister Crowley is mentioned by name in the song, Quicksand. Glam famously revives the 50s and to a lesser extent, the 20s. I would add the Blavatsky scented 1890s too.

Young Mod Dreaming

But back to Tyrannosaurus Rex. The funny thing about this duo – Bolan and Steve Peregrine Took (replaced by Mickey Finn on the fourth album) – is that, although they sound like a freak folk band, folk music isn’t at the heart of the sound. It’s something else. Yes, it’s rockabilly. I know it’s a stretch but look at two of the song titles on the first album. Hot Rod Mama, Mustang Ford. It’s a bit hard to imagine The Incredible String Band doing songs about classic American cars, isn’t it?

I suppose this is an important point for me because it defines what I love about Glam music. It’s beautiful, simple, rock and roll. Glam is not prog or psychedelia though it has some aspects of both. It is closer in spirit, if not always in sound, to 1950s style rock and roll. It redefines it, speeds it up, slows it down and adds crazy chords to it. But the greasy stuff is still the point of reference. The anxiety is in the influence of Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent rather than the glam practitioners’ immediate predecessors, Hendrix et al.

Fifties rock and roll is there if you look for it. The Cat Crept In by the lesser known band Mud comes to mind immediately. Suzi Quatro, who Reynolds contextualizes very well here, is another example. David Essex’s Rock On, T Rex’s I like to Boogie, and Drivin’ Sister by Mott the Hoople are other possibilities. In fact, Mott The Hoople’s metamusical commentaries like All The Way From Memphis and The Golden Age of Rock and Roll all reference the early period of the music. It’s worth remembering too that Bowie claimed Ziggy Stardust was inspired by a conversation with Vince Taylor, the English rocker best known for the original Brand New Cadillac.

So what was going on in the early 70s? Musically speaking, a lot of stuff, including prog, singer song writers, country rock, boogie rock, art rock, hard rock, soft rock and so on. As the punk year of 1976 drew closer it became increasingly clear that the centre couldn’t hold. A whole bunch of bands and genres were going to be swept away. So goodbye Foghat. I’d be happy to argue about this over a Guinness but I think glam was punk in the womb. The term punk rock was being batted around in the early seventies to describe everyone from Bruce Springsteen – a huge influence on Bowie’s post Ziggy period incidentally – to Alice Cooper, a band that gets a fair bit of space in Reynolds’ book. If punk was a rejection of the sixties’ values, it seems to me that they had already been comprehensively rejected by Bowie, Bolan, Ian Hunter, not to mention Lou Reed, Iggy Pop, and The New York Dolls.

That’s what my book about glam might look like. Simon Reynolds has a slightly different take. He doesn’t deny the clear line from glam to punk but he is far more interested in the journey from glam to post punk. I really enjoyed reading this book but I wasn’t always with him when he was talking about the music itself. What I like about Bowie’s Ziggy period is Mick Ronson’s guitar playing. I hear great rock and roll, Reynolds hears string arrangements. They are both there so it is a matter of taste, I guess. As with his earlier book Rip It Up and Start Again, he seems to be primarily interested in the non rock and roll influences and elements in popular music. In that book, he seemed to be suggesting that a lot of high concept early eighties bands were somehow more exciting than the punk bands that preceded them. To each his own, but for those of us who were teenagers when pretentious ‘post punk’ was evolving into banal ‘new wave,’ 1977-style punk sounded pretty good.

Similarly in Shock and Awe, Reynolds sees glam as part of a long tradition that stretches back to old Hollywood and reaches up to Lady Gaga. I don’t dispute this but, for me, it’s the killer riffs and the sheer three chord fun of it that makes it my comfort music. Slade, who Reynolds rightly suggests have been unfairly forgotten, are wonderful purveyors of power pop. They don’t have to be anything more. The Sweet are The Monkees of glam but at their best are a joyful reminder of good times and warm summer evenings.

Similarly in Shock and Awe, Reynolds sees glam as part of a long tradition that stretches back to old Hollywood and reaches up to Lady Gaga. I don’t dispute this but, for me, it’s the killer riffs and the sheer three chord fun of it that makes it my comfort music. Slade, who Reynolds rightly suggests have been unfairly forgotten, are wonderful purveyors of power pop. They don’t have to be anything more. The Sweet are The Monkees of glam but at their best are a joyful reminder of good times and warm summer evenings.

Reynolds’ book must be read. It is well researched, beautifully written, and comes from the heart. Despite my misgivings about his approach to Bowie’s music, I believe he has written the definitive account of the man’s early career. Glam, like many musical genres, is difficult to define and impossible to date. This book will challenge your ideas about the period and the artists mentioned. It will get you listening to some albums you may not have heard. I’m now stuck on Cockney Rebel’s first two records. You might start listening to Alice Cooper again for the first time since junior high. You might check out early Sparks. You might see Queen in a different light. No, really!

This book is up for the Penderyn Prize. I think it will win.

Teasers: If you thought you couldn’t dislike Don Henley any more, wait until you hear his views on The New York Dolls. Kiss, and in particular their drummer, are dismissed in one brutal paragraph so don’t worry, you won’t be compelled to revisit Hotter Than Hell.

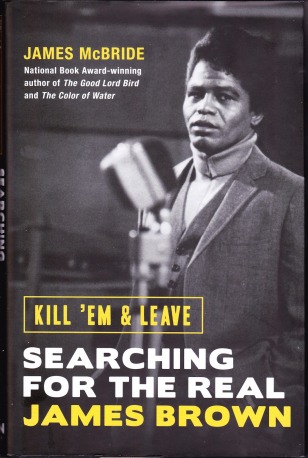

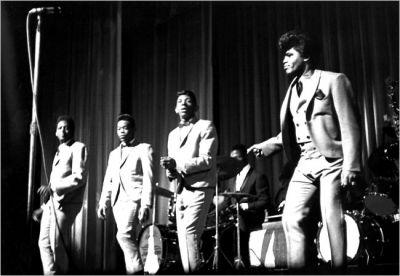

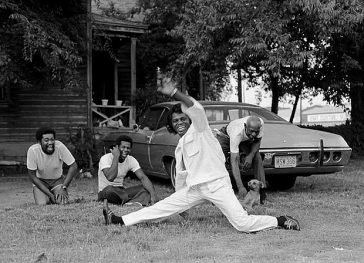

Kill ’Em And Leave: Searching for James Brown and the American Soul by James McBride, Spiegel & Grau 2016

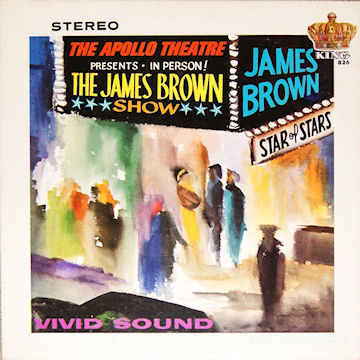

Kill ’Em And Leave: Searching for James Brown and the American Soul by James McBride, Spiegel & Grau 2016 I have only ever been a casual fan of James Brown. Like everyone else, I have owned Live at the Apollo in at least four formats, along with a greatest hits collection purchased during a brief teenage Mod phase. I saw him once too. In the mid 80s he played the Ontario Place Forum in Toronto with its revolving stage. It was a strange show. He did about five songs. Two of them were It’s A Man’s World. Then he came out with the cape, etc, for an encore. You guessed it, It’s A Man’s World one more time. I walked out of there like Robert Bly with a six-pack.

I have only ever been a casual fan of James Brown. Like everyone else, I have owned Live at the Apollo in at least four formats, along with a greatest hits collection purchased during a brief teenage Mod phase. I saw him once too. In the mid 80s he played the Ontario Place Forum in Toronto with its revolving stage. It was a strange show. He did about five songs. Two of them were It’s A Man’s World. Then he came out with the cape, etc, for an encore. You guessed it, It’s A Man’s World one more time. I walked out of there like Robert Bly with a six-pack. James McBride’s provocative account of Brown’s career makes one thing clear. The self styled Godfather of Soul does not fit easily into the received story of rock and roll. Motown makes sense. The Beatles drew from Motown. Chess makes sense. The Rolling Stones found something there. But James Brown’s legacy, in rock and roll at least, is less obvious. The story of his upstaging of the Stones is famous. Keith Richards has said that trying to follow him was the dumbest thing the band ever did. Brown, by some accounts, begat funk which begat disco. Okay, but we’re still talking about tributaries that exist outside of the rock and roll critical river. James McBride’s point here is never stated explicitly but his meaning is clear. James Brown is central to the African American experience of popular music. The standard Elvis – Beatles – Bowie – Punk – and so on story is arguably a very white one that, while not excluding black music, does sideline it. Elijah Wald explored this theme in his book How The Beatles Destroyed Rock and Roll a few years ago. James Brown’s story is certainly illustrative of it. If you’re shaking your head, think about this: The Beatles have appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone more than 30 times. James Brown, one of the key innovators in popular music, has appeared twice. The first time, in 1989, was well after his heyday and the second time, 2006, was after his death.

James McBride’s provocative account of Brown’s career makes one thing clear. The self styled Godfather of Soul does not fit easily into the received story of rock and roll. Motown makes sense. The Beatles drew from Motown. Chess makes sense. The Rolling Stones found something there. But James Brown’s legacy, in rock and roll at least, is less obvious. The story of his upstaging of the Stones is famous. Keith Richards has said that trying to follow him was the dumbest thing the band ever did. Brown, by some accounts, begat funk which begat disco. Okay, but we’re still talking about tributaries that exist outside of the rock and roll critical river. James McBride’s point here is never stated explicitly but his meaning is clear. James Brown is central to the African American experience of popular music. The standard Elvis – Beatles – Bowie – Punk – and so on story is arguably a very white one that, while not excluding black music, does sideline it. Elijah Wald explored this theme in his book How The Beatles Destroyed Rock and Roll a few years ago. James Brown’s story is certainly illustrative of it. If you’re shaking your head, think about this: The Beatles have appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone more than 30 times. James Brown, one of the key innovators in popular music, has appeared twice. The first time, in 1989, was well after his heyday and the second time, 2006, was after his death. McBride himself tasted literary stardom a few years ago with his memoir, The Color of Water. He is a formidable prose writer who has also worked as a professional musician. It’s not surprising that this book made so many ‘best of’ lists for 2016. As one era in the White House ends and we await the full implications of the one that will follow, McBride’s story of a man who scored his first hit in 1956 couldn’t be more relevant. The search for the soul of America is ongoing.

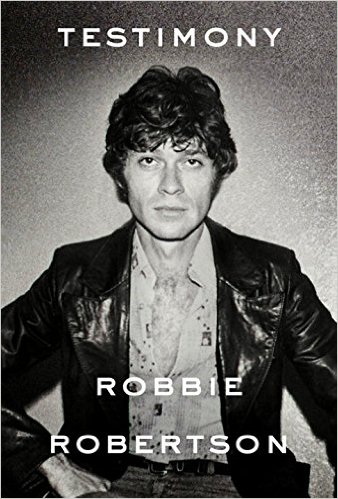

McBride himself tasted literary stardom a few years ago with his memoir, The Color of Water. He is a formidable prose writer who has also worked as a professional musician. It’s not surprising that this book made so many ‘best of’ lists for 2016. As one era in the White House ends and we await the full implications of the one that will follow, McBride’s story of a man who scored his first hit in 1956 couldn’t be more relevant. The search for the soul of America is ongoing. Testimony by Robbie Robertson, Deckle Edge 2016

Testimony by Robbie Robertson, Deckle Edge 2016

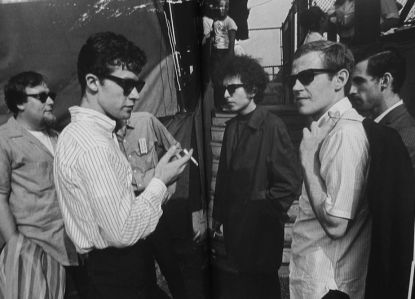

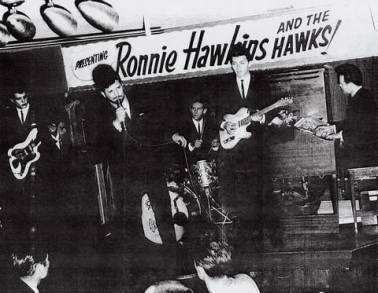

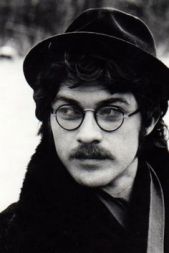

Robertson is particularly good on his early days with Ronnie Hawkins and the evolution of The Hawks. His growing friendship with Levon is at the heart of these sections but he also brings Hawkins, the sort of Dumbledore figure in The Band’s story, to life in all his manic glory. Slowly, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, and the arch eccentric, Garth Hudson of London Ontario, make their way into the Hawks. The band conquers Yonge St and all its young women. They play dives at Wasaga Beach, they play dives on the Mississippi. Robertson was 16 when he joined up. When The Band’s first album appeared in 1968, they had been on the road since the late 50s. The Beatles’ Hamburg period is, at least according to Malcolm Gladwell, an important factor in everything that followed. There is a special ingredient in The Band’s music that is sometimes hard to identify. Robbie’s wonderful evocation of the band’s early years provides an important clue, I believe. The threads of rockabilly, rhythm and blues, pop, blues, and a country ballad or two are all part of the fabric of The Band’s sound.

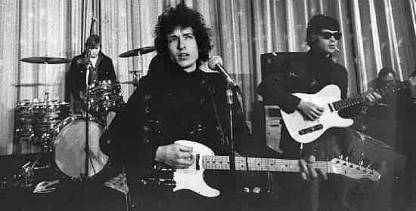

Robertson is particularly good on his early days with Ronnie Hawkins and the evolution of The Hawks. His growing friendship with Levon is at the heart of these sections but he also brings Hawkins, the sort of Dumbledore figure in The Band’s story, to life in all his manic glory. Slowly, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, and the arch eccentric, Garth Hudson of London Ontario, make their way into the Hawks. The band conquers Yonge St and all its young women. They play dives at Wasaga Beach, they play dives on the Mississippi. Robertson was 16 when he joined up. When The Band’s first album appeared in 1968, they had been on the road since the late 50s. The Beatles’ Hamburg period is, at least according to Malcolm Gladwell, an important factor in everything that followed. There is a special ingredient in The Band’s music that is sometimes hard to identify. Robbie’s wonderful evocation of the band’s early years provides an important clue, I believe. The threads of rockabilly, rhythm and blues, pop, blues, and a country ballad or two are all part of the fabric of The Band’s sound. Speaking of the Nobel Laureate, Robbie is very good on the 1966 tour. There has been so much written about it that I wondered if he would bother spending too much time there. He does and manages to provide a unique perspective. Dylan is one of a long series of ‘father figures’ in Robertson’s life. He never actually says this but Ronnie Hawkins gives way to Levon who gives way to Dylan who gives way to Albert Grossman who gives way to David Geffen who gives way to Martin Scorcese. Dylan’s intelligence and absolute cool headedness in every situation impresses the young guitarist as he ducks flying objects night after night on the ‘Judas’ tour.

Speaking of the Nobel Laureate, Robbie is very good on the 1966 tour. There has been so much written about it that I wondered if he would bother spending too much time there. He does and manages to provide a unique perspective. Dylan is one of a long series of ‘father figures’ in Robertson’s life. He never actually says this but Ronnie Hawkins gives way to Levon who gives way to Dylan who gives way to Albert Grossman who gives way to David Geffen who gives way to Martin Scorcese. Dylan’s intelligence and absolute cool headedness in every situation impresses the young guitarist as he ducks flying objects night after night on the ‘Judas’ tour. Following the section on the first album, the tone of Testimony shifts in a subtle way. Rick Danko manages to break his neck in a car accident before their first tour and Richard Manuel’s drinking starts to make an impact. Then Levon Helm discovers heroin. Robbie Robertson is a gentleman. He doesn’t scold or preach but the sense of a lost opportunity is discernible in the folds of his prose. I doubt that anyone will ever top this band’s first two albums but I think Robbie feels as though the records that followed could have been a lot better. He doesn’t think much of Cahoots, for instance. While it isn’t perhaps on par with its three predecessors, an album with Life is a Carnival, When I Paint My Masterpiece, and The River Hymn still must rank as one of the ten best albums of the 1970s.

Following the section on the first album, the tone of Testimony shifts in a subtle way. Rick Danko manages to break his neck in a car accident before their first tour and Richard Manuel’s drinking starts to make an impact. Then Levon Helm discovers heroin. Robbie Robertson is a gentleman. He doesn’t scold or preach but the sense of a lost opportunity is discernible in the folds of his prose. I doubt that anyone will ever top this band’s first two albums but I think Robbie feels as though the records that followed could have been a lot better. He doesn’t think much of Cahoots, for instance. While it isn’t perhaps on par with its three predecessors, an album with Life is a Carnival, When I Paint My Masterpiece, and The River Hymn still must rank as one of the ten best albums of the 1970s. This is something different, an unusual rock and roll memoir where the paucity of information functions as a kind of subtext. Robbie hasn’t come to terms with The Band and has perhaps been stung by his ‘Yoko-isation’ by fans and critics. I enjoyed Testimony enormously but this is perhaps a more melancholy book than the author intended.

This is something different, an unusual rock and roll memoir where the paucity of information functions as a kind of subtext. Robbie hasn’t come to terms with The Band and has perhaps been stung by his ‘Yoko-isation’ by fans and critics. I enjoyed Testimony enormously but this is perhaps a more melancholy book than the author intended.

So let’s throw another log on the equation. Those two albums appeared within six months of each other in the mid 1960s. Hoodoo Man Blues by Junior Wells was released at about the same time. Surely this knocks it out of Wrigley Field. Bloomfield and Clapton are great blues players but compared to Buddy Guy? Butterfield is one of the great harp players but, senator, he’s no Junior Wells. Case closed then. Well, maybe. Hoodoo Man Blues departs, quite dramatically at points, from the electric ‘country’ style associated with Muddy Waters, Wolf, and others. Listen to the first track, Snatch It Back and Hold It. It sounds a lot more like Papa’s got a Brand New Bag than Two Trains Running. Look over the track list. There’s a Kenny Burrell song on there! It’s a sophisticated and beautiful record but is it the blues? The ‘real’ blues?

So let’s throw another log on the equation. Those two albums appeared within six months of each other in the mid 1960s. Hoodoo Man Blues by Junior Wells was released at about the same time. Surely this knocks it out of Wrigley Field. Bloomfield and Clapton are great blues players but compared to Buddy Guy? Butterfield is one of the great harp players but, senator, he’s no Junior Wells. Case closed then. Well, maybe. Hoodoo Man Blues departs, quite dramatically at points, from the electric ‘country’ style associated with Muddy Waters, Wolf, and others. Listen to the first track, Snatch It Back and Hold It. It sounds a lot more like Papa’s got a Brand New Bag than Two Trains Running. Look over the track list. There’s a Kenny Burrell song on there! It’s a sophisticated and beautiful record but is it the blues? The ‘real’ blues?

There is a suggestion, raised a couple of times in the book, that the southern, Jim Crow Mississippi sources of the early Chicago sound are simply a different listening experience for black audiences. Possibly this is why the black audiences that have stuck with blues apparently favour the smoother, more urban sounds that white devotees of the genre, like me for instance, find dull and overproduced. So where does that leave us? What’s authentic now? The rough hewn sound of Muddy’s earlier sides or the slick lines of ZZ Hill, an artist credited with bringing blues back to its original audiences in the early 80s? Harper admits that he had never heard of ZZ Hill in 1982.

There is a suggestion, raised a couple of times in the book, that the southern, Jim Crow Mississippi sources of the early Chicago sound are simply a different listening experience for black audiences. Possibly this is why the black audiences that have stuck with blues apparently favour the smoother, more urban sounds that white devotees of the genre, like me for instance, find dull and overproduced. So where does that leave us? What’s authentic now? The rough hewn sound of Muddy’s earlier sides or the slick lines of ZZ Hill, an artist credited with bringing blues back to its original audiences in the early 80s? Harper admits that he had never heard of ZZ Hill in 1982.

How To Listen To Jazz by Ted Gioia, Basic Books, 2016

How To Listen To Jazz by Ted Gioia, Basic Books, 2016

In the second chapter, however, he focuses on the individual musician. He uses the word ‘intentionality’ to describe the way jazz musicians approach phrasing. They mean it, man! When John Coltrane blows a note, there is nothing the least bit accidental about the manner in which it is played. It might start off quietly before rising in volume or it might be a quick blast. Same note, totally different effect. Later, in a section on pitch, Gioia tells the story of Sidney Bechet giving a saxophone lesson to a journalist in the 1940s. “I’m going to give you one note today. See how many ways you can play that note – growl it, smear it, flat it, sharp it, do anything you want to it. That’s how you express your feelings in this music. It’s like talking.” There’s Buber again.

In the second chapter, however, he focuses on the individual musician. He uses the word ‘intentionality’ to describe the way jazz musicians approach phrasing. They mean it, man! When John Coltrane blows a note, there is nothing the least bit accidental about the manner in which it is played. It might start off quietly before rising in volume or it might be a quick blast. Same note, totally different effect. Later, in a section on pitch, Gioia tells the story of Sidney Bechet giving a saxophone lesson to a journalist in the 1940s. “I’m going to give you one note today. See how many ways you can play that note – growl it, smear it, flat it, sharp it, do anything you want to it. That’s how you express your feelings in this music. It’s like talking.” There’s Buber again.

Murray Talks Music: Albert Murray on Jazz and Blues by Albert Murray and Paul Devlin (Editor), University of Minnesota Press, 2016

Murray Talks Music: Albert Murray on Jazz and Blues by Albert Murray and Paul Devlin (Editor), University of Minnesota Press, 2016 His love of jazz goes far beyond his vast knowledge of the music and its players. For Murray, jazz is the purest form of American art. Like the country itself, it is about innovation and improvisation. Jazz music, he says, is the sound of a restless nation pushing against boundaries and frontiers. It is also, for Murray, an African American art form. Some of his critics, notably Terry Teachout, have suggested that he underrated white jazz artists but Murray’s views here are far more complex. His position was that the race problem in America is one of definition and artificial lines. America for Murray was an idea, rather than a geopolitical or economic entity. He believed that African Americans were the ‘real’ Americans because they arrived from Africa with no language and no culture. They absorbed the culture of America and practiced it in its purest form, untainted by a sense of Europe as a center. They were thus able to create jazz, the greatest and perhaps only truly American art form. His first book, The Omni Americans (1970), a response to Patrick Moynihan’s damning 1965 report on the state of African Americans, suggests that the way forward could be in a redefining of American culture, to recognize the contribution of everyone involved, rather than any one group. Sadly, this probably still seems overly idealistic almost 50 years later. However, while pondering this, it occurred to me that the blues heritage of Mississippi and Chicago are now institutionalized in a manner that would have seemed unlikely even 25 years ago. When I visited Maxwell Street, Chicago, in the early 90s, the market was closed and there was no sign that this was one of the crucibles of American music. It is now heritage listed, the market has reopened, and tourism has revived what was a very depressed neighbourhood. Richard Daley’s son, of all people, made this happen! It would be lovely to think that we might one day say that music provided the groundwork for a real change in race relations in America.

His love of jazz goes far beyond his vast knowledge of the music and its players. For Murray, jazz is the purest form of American art. Like the country itself, it is about innovation and improvisation. Jazz music, he says, is the sound of a restless nation pushing against boundaries and frontiers. It is also, for Murray, an African American art form. Some of his critics, notably Terry Teachout, have suggested that he underrated white jazz artists but Murray’s views here are far more complex. His position was that the race problem in America is one of definition and artificial lines. America for Murray was an idea, rather than a geopolitical or economic entity. He believed that African Americans were the ‘real’ Americans because they arrived from Africa with no language and no culture. They absorbed the culture of America and practiced it in its purest form, untainted by a sense of Europe as a center. They were thus able to create jazz, the greatest and perhaps only truly American art form. His first book, The Omni Americans (1970), a response to Patrick Moynihan’s damning 1965 report on the state of African Americans, suggests that the way forward could be in a redefining of American culture, to recognize the contribution of everyone involved, rather than any one group. Sadly, this probably still seems overly idealistic almost 50 years later. However, while pondering this, it occurred to me that the blues heritage of Mississippi and Chicago are now institutionalized in a manner that would have seemed unlikely even 25 years ago. When I visited Maxwell Street, Chicago, in the early 90s, the market was closed and there was no sign that this was one of the crucibles of American music. It is now heritage listed, the market has reopened, and tourism has revived what was a very depressed neighbourhood. Richard Daley’s son, of all people, made this happen! It would be lovely to think that we might one day say that music provided the groundwork for a real change in race relations in America.

Every Song Ever: Twenty Ways to Listen in a Musical Age of Plenty by Ben Ratliff, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016

Every Song Ever: Twenty Ways to Listen in a Musical Age of Plenty by Ben Ratliff, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016 The chapter on ‘Transmission’ is particularly interesting. He quotes the 19th century writer Evard Hanslick who wrote that ‘music mimics the motion of feelings’. This rather romantic idea was dismissed by the formalist critics of the early 20th century who tried to quantify the effects of music with elaborate theory and somewhat pseudo scientific ideas about our relationship to it. Ratliff points to the Sufi tradition and the wildly spiritual music of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan as evidence that the place where music comes from is no simple matter. John Lennon’s performance of Julia, one of his great moments, is mentioned here too.

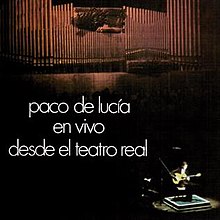

The chapter on ‘Transmission’ is particularly interesting. He quotes the 19th century writer Evard Hanslick who wrote that ‘music mimics the motion of feelings’. This rather romantic idea was dismissed by the formalist critics of the early 20th century who tried to quantify the effects of music with elaborate theory and somewhat pseudo scientific ideas about our relationship to it. Ratliff points to the Sufi tradition and the wildly spiritual music of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan as evidence that the place where music comes from is no simple matter. John Lennon’s performance of Julia, one of his great moments, is mentioned here too. But the other aspect of this book is the examples that he uses to illustrate his various claims. The book is not long, 272 pages, but it will take you weeks to read because you can’t help tracking down the songs and albums he mentions. They are threaded through the text and featured in a list at the end of each chapter. Hence the serendipitous appearance of this book as I vowed to listen to more unfamiliar music. In the ‘Slowness’ chapter, I discovered Dadawah’s Peace and Love album, some magic mid seventies reggae. The ‘Discrepancy’ chapter yielded Willie Colon’s Lo Mato album from 1973. The improvisation chapter alerted me to the music of Derek Bailey, an avant garde guitarist, and Paco De Lucia’s scorching 1975 En Vivo Desde el Teatro Real album. So much good stuff. I ended up keeping a notebook nearby so I could make a list of albums, both known and unknown, to listen to later. It’s that kind of a book.

But the other aspect of this book is the examples that he uses to illustrate his various claims. The book is not long, 272 pages, but it will take you weeks to read because you can’t help tracking down the songs and albums he mentions. They are threaded through the text and featured in a list at the end of each chapter. Hence the serendipitous appearance of this book as I vowed to listen to more unfamiliar music. In the ‘Slowness’ chapter, I discovered Dadawah’s Peace and Love album, some magic mid seventies reggae. The ‘Discrepancy’ chapter yielded Willie Colon’s Lo Mato album from 1973. The improvisation chapter alerted me to the music of Derek Bailey, an avant garde guitarist, and Paco De Lucia’s scorching 1975 En Vivo Desde el Teatro Real album. So much good stuff. I ended up keeping a notebook nearby so I could make a list of albums, both known and unknown, to listen to later. It’s that kind of a book. 1966: The Year the Decade Exploded, Jon Savage, Faber and Faber 2015

1966: The Year the Decade Exploded, Jon Savage, Faber and Faber 2015 At the moment on my coffee table, there are books called 1607 (James Shapiro’s follow up to 1599), 1966, Detroit 67, and a novel by Garth Risk Hallberg called City on Fire which appears to be set entirely in 1977 although it’s 900 pages long and I’m only halfway through it. It might be 1979 when I finish. Or 2017. On my kobo, there is a book by David Browne called Fire and Rain that is all about 1970 and one from a few years ago called 1968 by Mark Kurlansky. They are all of interest but when ‘1996’ appears, don’t expect a review. I didn’t like anything about that whole decade.

At the moment on my coffee table, there are books called 1607 (James Shapiro’s follow up to 1599), 1966, Detroit 67, and a novel by Garth Risk Hallberg called City on Fire which appears to be set entirely in 1977 although it’s 900 pages long and I’m only halfway through it. It might be 1979 when I finish. Or 2017. On my kobo, there is a book by David Browne called Fire and Rain that is all about 1970 and one from a few years ago called 1968 by Mark Kurlansky. They are all of interest but when ‘1996’ appears, don’t expect a review. I didn’t like anything about that whole decade.

Some of these chapters are more convincing than others. His evocation of homosexuality in 1966 is particularly well done. The Tornados ‘Do you come here often?’, is widely thought of as the first ‘gay’ pop song – for those who missed the subtext of Tutti Frutti and countless other 1950s singles. Joe Meek, the legendary producer of this song, had begun his long slide into the madness that would end in his death in 1967. Like Brian Epstein, he led a secret life and had been subjected to arrest and blackmail attempts over the years. The laws were changing but it was still a difficult time to be gay in England. The chapter also picks up the story of San Francisco in that year. The Gay rights movement, in most people’s minds, begins with Stonewall in 1969 but Savage shows that it was already crystalising in 1966.

Some of these chapters are more convincing than others. His evocation of homosexuality in 1966 is particularly well done. The Tornados ‘Do you come here often?’, is widely thought of as the first ‘gay’ pop song – for those who missed the subtext of Tutti Frutti and countless other 1950s singles. Joe Meek, the legendary producer of this song, had begun his long slide into the madness that would end in his death in 1967. Like Brian Epstein, he led a secret life and had been subjected to arrest and blackmail attempts over the years. The laws were changing but it was still a difficult time to be gay in England. The chapter also picks up the story of San Francisco in that year. The Gay rights movement, in most people’s minds, begins with Stonewall in 1969 but Savage shows that it was already crystalising in 1966. ‘global village’ by 1966 and most of the events in the UK and US were mirrored in other places. Others may be able to point to music related events in Africa or even the Middle East. Please point!

‘global village’ by 1966 and most of the events in the UK and US were mirrored in other places. Others may be able to point to music related events in Africa or even the Middle East. Please point! Lives of the Poets (with Guitars): Thirteen Outsiders Who Changed Modern Music Ray Robertson, Biblioasis 2016

Lives of the Poets (with Guitars): Thirteen Outsiders Who Changed Modern Music Ray Robertson, Biblioasis 2016 Many novelists attempt this trick. Not many get there. Novels about rock and roll bands usually fall in a great big heap when the writer tries to describe the music. I’m happy to be corrected on this one. Please drench me in the names of credible rock and roll novels. I can think of three. The Doubleman is one, Paul Quarrington’s Whale Music is another. The final and greatest of all is Ray Robertson’s 2002 novel, Moody Food.

Many novelists attempt this trick. Not many get there. Novels about rock and roll bands usually fall in a great big heap when the writer tries to describe the music. I’m happy to be corrected on this one. Please drench me in the names of credible rock and roll novels. I can think of three. The Doubleman is one, Paul Quarrington’s Whale Music is another. The final and greatest of all is Ray Robertson’s 2002 novel, Moody Food. The first essay on Gene Clark sets the tone (and the volume, ha ha!). Clark is a notable cult figure. His album No Other can sit comfortably next to a whole bunch of other ambitious and brilliant albums that were completely ignored when they appeared. Clark’s sad tale is a staple of magazines like MOJO and Uncut but Ray tells it in such an affecting manner that it felt as though I was reading it for the first time. This musician’s musical journey was an unusual one that spanned several decades. Ray uses his considerable storytelling abilities to give his music a cohesive frame. This would be insupportable if the music wasn’t described with such clarity and detail. I could hear these albums as I read. That’s impressive.

The first essay on Gene Clark sets the tone (and the volume, ha ha!). Clark is a notable cult figure. His album No Other can sit comfortably next to a whole bunch of other ambitious and brilliant albums that were completely ignored when they appeared. Clark’s sad tale is a staple of magazines like MOJO and Uncut but Ray tells it in such an affecting manner that it felt as though I was reading it for the first time. This musician’s musical journey was an unusual one that spanned several decades. Ray uses his considerable storytelling abilities to give his music a cohesive frame. This would be insupportable if the music wasn’t described with such clarity and detail. I could hear these albums as I read. That’s impressive.

I am not a hardcore Sonic Youth fan. I saw them once, opening for Neil Young, and I have two or three of their albums. The wonderful thing about this book is that it doesn’t matter. She has so many interesting things to say about art, about her friendships with people like Kurt Cobain, her experiences as a woman in the blokey world of alternative rock, motherhood, and her brief time as a fashion designer. I suspect that even readers who had never heard of Sonic Youth would be charmed by her story. That said, fans will relish the detail with which she outlines how certain songs came to be written. She is clearly inspired by the books she reads and she mentions many of them. Keep a pen handy.

I am not a hardcore Sonic Youth fan. I saw them once, opening for Neil Young, and I have two or three of their albums. The wonderful thing about this book is that it doesn’t matter. She has so many interesting things to say about art, about her friendships with people like Kurt Cobain, her experiences as a woman in the blokey world of alternative rock, motherhood, and her brief time as a fashion designer. I suspect that even readers who had never heard of Sonic Youth would be charmed by her story. That said, fans will relish the detail with which she outlines how certain songs came to be written. She is clearly inspired by the books she reads and she mentions many of them. Keep a pen handy.