Memphis ’68: The Tragedy of Southern Soul by Stuart Cosgrove, Polygon, 2017

Memphis ’68: The Tragedy of Southern Soul by Stuart Cosgrove, Polygon, 2017

The original Memphis is 15 miles south of Cairo in Egypt. It was the capital about three thousand years ago and is now a popular stop on the tourist trail. Like many ancient cities, it was filled with temples dedicated to an array of deities, some well known to this day, some obscure, and and and some whose sole memorial is a name engraved in a barely translatable language.

Its namesake in Tennessee is a site that predates European settlement by at least a millennium. The Chickasaws had been there for hundreds of years when Hernando De Soto came by in the 1500s. They were still there when Andrew Jackson founded the city and named it after the Egyptian place 300 years later. It was clearly an appealing place to settle, that famous bluff walked by Johnny Cash’s lost love, raising a few eyeballs before she continued down the Mississippi River. Like the original Memphis, its economic life was based on a large river and its fortunes have always been tied to it. In the ancient city, the number of different temples for different gods is probably explained by the proximity to the river. The population was always in flux and visitors came and went, leaving behind items of their cultural baggage.

The Egyptian Memphis lost influence through the usual series of economic and political changes that constitute history. Memphis, Tennessee can also seem like a city of the past. The name evokes a much earlier period in American history. Riverboats, jug bands, WC Handy, Furry Lewis, Sun Records, and Otis Redding come to mind. Only New Orleans tops it as a staging ground for the old romantic America. But here’s an argument starter: In terms of diversity and influence, Memphis is by far the most important musical hub in America. Blues, RnB, Rockabilly, Soul, and Rock and Roll all thrived in this city. Try to imagine Elvis coming from any other city in the US. It’s not easy, is it?

Old Gods at Sun Records on Union Avenue.

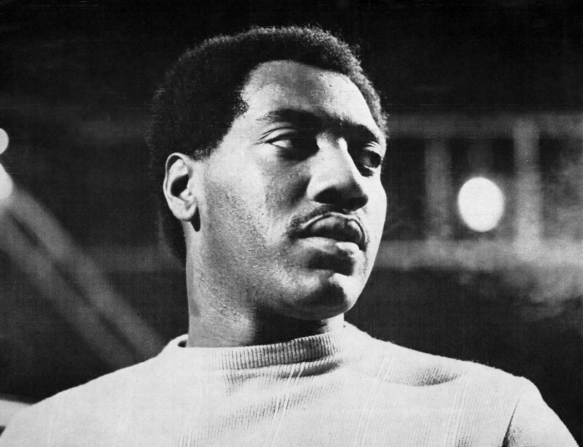

Stuart Cosgrove’s latest book, Memphis ’68: The Tragedy of Southern Soul documents the year from which many believe the city never fully recovered. Otis Redding’s death in December 1967 has long been acknowledged as the beginning of the end for Stax Records. The assassination of Martin Luther King on the balcony of a Memphis motel four months later devastated the whole country and seemed to suck the life out of a town already reeling from the first stirrings of the globalized neo liberal economics that continue to depress the American South. Martin Luther King was in town to support a strike by the city’s sanitation workers. Memphis had a long history of corrupt local politics, and a longer history of racism. The term segregation only begins to describe a city so divided that each community barely realized the other was there. The sanitation workers were invisible despite providing an essential service. Martin Luther King made his famous ‘I have been to the mountaintop’ speech at a rally for them the day before he died.

Booker T, Duck Dunn, Steve Cropper, Carla Thoma

Strangely enough, the situation in wider Memphis was not reflected within the walls of 926 East McLemore Ave. Stax Records was, briefly anyway, a complete anomaly in the city. It is one of the great ironies that the white guitarist, Steve Cropper, wrote In the Midnight Hour with Wilson Pickett in a room at the Lorraine Motel where Martin Luther King was murdered three years later. I don’t know how many different accounts I have read of this period at Stax Records but I’m always moved by the story. There is something fairytale-like about this small space in Memphis where music was important and race wasn’t. It didn’t last, of course, but for a moment there, right under the noses of the racist power elite in Tennessee, a wonderful model for desegregation was developing.

MLK in Memphis

Memphis ’68 is the second in a proposed trilogy that includes last year’s Detroit ’67 (reviewed here in April 2016) and next year’s Harlem ’69. Cosgrove is a great storyteller and this book is a deserving winner of the 2018 Penderyn Prize for books about music. Though it is, broadly speaking, a social history, music is at its centre. Cosgrove has a deep and longstanding love of soul music that he combines with an encyclopedic knowledge of the genre’s artists, songs, and labels. Because of the dramatic nature of MLK’s assassination and the resulting riots, he faced a real challenge here telling this well-known story in a fresh way. His account of The Invaders, a Memphis version of the Black Panthers that included at least one Stax musician in their ranks, adds another layer. The month-by-month assessment of 1968 in Memphis is done through the stories of both musicians and ordinary citizens of the city. As with his Detroit book, the effect is immersive and engaging.

Memphis Rent Party: The Blues, Rock & Soul in Music’s Hometown by Robert Gordon

Memphis Rent Party: The Blues, Rock & Soul in Music’s Hometown by Robert Gordon

Robert Gordon is a Memphis native who was seven in 1968 and remembers seeing tanks on the streets after the assassination. His love for his hometown is well documented in books like the sensational It Came From Memphis and Respect Yourself: Stax Records and the Soul Explosion. He has also made a number of films about Memphis musicians. Blues fans will be familiar with his biography of Muddy Waters, Can’t Be Satisfied. All of his books are on the syllabus. You must read them.

His latest is a collection of articles, reviews, liner notes and unpublished pieces called Memphis Rent Party: The Blues, Rock & Soul in Music’s Hometown. I read it immediately after finishing Cosgrove’s book and it makes a fine companion. If the heady tale of Memphis’ most dramatic year is dinner, this is a rich dessert followed by lovely whiskey.

Gordon is, by his own admission, a member of the Peter Guralnick school of music writing. His knowledge of music is deep but the musicians fascinate him too. These pieces put you at the table with the subjects. The article on Jeff Buckley’s final days is a case in point. The singer’s tragically short career has been dissected and rehashed many times but this piece is revelatory. Buckley was searching for something in Memphis and Gordon was fortunate enough to spend some time with him while he made his last recordings and absorbed some of the musical atmosphere of the city. It’s a poignant article. Honestly, while I was reading it, I felt the same way I did when I heard he had died that day in 1997. I also went running to my CD shelves to find my copy of Sketches of My Sweetheart the Drunk. You will too!

But most of the pieces here deal with Memphis musicians. James Carr, a soul great that has never had anywhere near the recognition he deserves, is profiled. His story is another sad one. He recorded the original, and by far the best, version of Dan Penn’s Dark End of the Street on Goldwax Records in 1967. It should have set him up for a lifetime’s career in music. Instead, he battled terrible mental health problems and substance abuse issues until his death in 2001. Gordon’s interview presents him with the almost Lear-like pathos of a delicate soul unraveling. This is something of a pattern in these essays. The brilliant Jazz pianist Phineas Newborn Jr suffered numerous nervous breakdowns after his initial success in the late 50s and even had his fingers broken in a bar one night. Gordon interviews his mother here and profiles his brother Calvin. Jerry McGill, a Sun Records recording artist and the subject of one of Gordon’s films, is another hard luck story albeit one with a mildly happy ending.

But most of the pieces here deal with Memphis musicians. James Carr, a soul great that has never had anywhere near the recognition he deserves, is profiled. His story is another sad one. He recorded the original, and by far the best, version of Dan Penn’s Dark End of the Street on Goldwax Records in 1967. It should have set him up for a lifetime’s career in music. Instead, he battled terrible mental health problems and substance abuse issues until his death in 2001. Gordon’s interview presents him with the almost Lear-like pathos of a delicate soul unraveling. This is something of a pattern in these essays. The brilliant Jazz pianist Phineas Newborn Jr suffered numerous nervous breakdowns after his initial success in the late 50s and even had his fingers broken in a bar one night. Gordon interviews his mother here and profiles his brother Calvin. Jerry McGill, a Sun Records recording artist and the subject of one of Gordon’s films, is another hard luck story albeit one with a mildly happy ending.

The spirit of Alex Chilton hangs over many of these tales and he is the subject of a long meditation towards the end of the book. Like Flies on Sherbert, an album produced by another Memphis deity, Jim Dickinson, is either a drunken mess or a sophisticated deconstruction of Memphis music, depending on your perspective. Gordon is a fan and maintained a long, though not always friendly relationship with the mercurial singer. Chilton’s sometime collaborator Tav Falco is also profiled here. Falco’s story is a reminder of the vibrant arts scene in Memphis in the 70s.

It would be tempting to finish by saying that, like Memphis in Egypt, Memphis Tennessee is now simply an open air museum that trades on past glories. While there are many temples to old gods – Graceland, Stax, Sun Records, and Beale Street, I suspect that Memphis can’t be consigned to ancient history just yet. Somewhere in those streets, the next Alex Chilton or James Carr or Steve Cropper is practicing guitar and dreaming about writing another chapter in the musical history of this remarkable city.

“Children by the million sing for Alex Chilton when he comes ’round”

Teasers: Martin Luther King was talking to a musician just before he died. He was making a request. Find out which song in Cosgrove’s book.

Otis Redding: An Unfinished Life by Jonathan Gould, Crown 2017

Otis Redding: An Unfinished Life by Jonathan Gould, Crown 2017

Gould weaves Redding’s story into the broader narrative of African American life in the mid 20th century. His generation of singers, including his occasional rival James Brown, followed the examples of Ray Charles and Sam Cooke who had both worked hard to maintain control over their careers. The young Otis had to prove himself several times in new neighborhoods when the family moved for work in the 1950s. The man that emerges in this book is no pushover and this is not the story of how a black entertainer was ripped off by unscrupulous white men. From the beginning, Otis chose the people around him carefully and, for the most part, avoided the usual pitfalls musicians encounter when their music begins to make money.

Gould weaves Redding’s story into the broader narrative of African American life in the mid 20th century. His generation of singers, including his occasional rival James Brown, followed the examples of Ray Charles and Sam Cooke who had both worked hard to maintain control over their careers. The young Otis had to prove himself several times in new neighborhoods when the family moved for work in the 1950s. The man that emerges in this book is no pushover and this is not the story of how a black entertainer was ripped off by unscrupulous white men. From the beginning, Otis chose the people around him carefully and, for the most part, avoided the usual pitfalls musicians encounter when their music begins to make money.

If you’ve already read the standard Stax Records books (see my list below), most of which cover Otis at great length, there are still many good reasons to read A Life Unfinished. The research is impeccable and perhaps it is time for a serious biography that goes beyond the music and addresses the wider implications of Otis Redding’s time on earth. Gould works hard to penetrate the somewhat mysterious inner life of the man. This is by no means some kind of iconoclastic Albert Goldman style biography but we are certainly left with a sense that there was a lot more to Otis than the genial image projected by his music.

If you’ve already read the standard Stax Records books (see my list below), most of which cover Otis at great length, there are still many good reasons to read A Life Unfinished. The research is impeccable and perhaps it is time for a serious biography that goes beyond the music and addresses the wider implications of Otis Redding’s time on earth. Gould works hard to penetrate the somewhat mysterious inner life of the man. This is by no means some kind of iconoclastic Albert Goldman style biography but we are certainly left with a sense that there was a lot more to Otis than the genial image projected by his music.

Young Soul Rebels: A Personal History of Northern Soul by Stuart Cosgrove, Polygot 2016

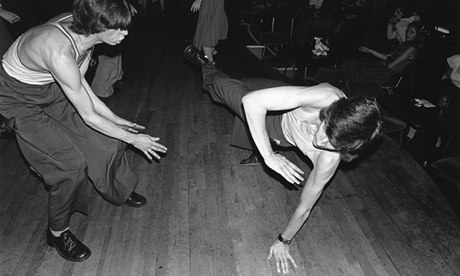

Young Soul Rebels: A Personal History of Northern Soul by Stuart Cosgrove, Polygot 2016 At some point in the late Sixties, the Mods divided into two factions. One group drifted into paisley shirts and faux pastoral lysergic afternoons in Hyde Park. The other group donned singlets and loose pants for heart murmuring nights of amphetamine cocktails and Northern Soul. Unlike the twisty yoga hand jive and starry eyed shuffle of the first group, Northern Soul dancing was acrobatically athletic. The clothes had to be loose enough to accommodate back flips, high kicks, and swallow dives. Many of the most famous male dancers were also involved in martial arts. As for female dancers, well, there was one young woman who turned a few heads with her moves at the Blackpool Mecca in the mid 70s. Her name was Jayne Torvill.

At some point in the late Sixties, the Mods divided into two factions. One group drifted into paisley shirts and faux pastoral lysergic afternoons in Hyde Park. The other group donned singlets and loose pants for heart murmuring nights of amphetamine cocktails and Northern Soul. Unlike the twisty yoga hand jive and starry eyed shuffle of the first group, Northern Soul dancing was acrobatically athletic. The clothes had to be loose enough to accommodate back flips, high kicks, and swallow dives. Many of the most famous male dancers were also involved in martial arts. As for female dancers, well, there was one young woman who turned a few heads with her moves at the Blackpool Mecca in the mid 70s. Her name was Jayne Torvill. Stuart Cosgrove covers the early years at Manchester’s Twisted Wheel nightclub, where the scene was born, but focuses on the most famous venue of all, Wigan Casino. He lovingly recreates the sights, sounds and olfactory sense of an evening there. The layout is important. It wasn’t just one big hall. There were smaller rooms where traditionalists could dance to early sixties sides without having to worry about the creeping funkiness of early 70s r’n’b. In other rooms there were pop up rare record markets where big money changed hands and discussions of music often grew heated. The main room, however, was where the seriously aerodynamic dancing took place and legendary DJs melted the floor with sides like Fred Hughes Baby Boy. Listen to it on YouTube and see if you can sit still. I dare you! At the end of the night which was actually the next morning, the DJ would play the ‘3 before 8’(am); Jimmy Radcliffe’s Long After Tonight Is All Over, Tobi Legend’s Time Will Pass You By and Dean Parrish’s I’m On My Way. The dancers would then make their way outside, blinking in the grey Sunday morning light and presumably heading for the nearest curry shop.

Stuart Cosgrove covers the early years at Manchester’s Twisted Wheel nightclub, where the scene was born, but focuses on the most famous venue of all, Wigan Casino. He lovingly recreates the sights, sounds and olfactory sense of an evening there. The layout is important. It wasn’t just one big hall. There were smaller rooms where traditionalists could dance to early sixties sides without having to worry about the creeping funkiness of early 70s r’n’b. In other rooms there were pop up rare record markets where big money changed hands and discussions of music often grew heated. The main room, however, was where the seriously aerodynamic dancing took place and legendary DJs melted the floor with sides like Fred Hughes Baby Boy. Listen to it on YouTube and see if you can sit still. I dare you! At the end of the night which was actually the next morning, the DJ would play the ‘3 before 8’(am); Jimmy Radcliffe’s Long After Tonight Is All Over, Tobi Legend’s Time Will Pass You By and Dean Parrish’s I’m On My Way. The dancers would then make their way outside, blinking in the grey Sunday morning light and presumably heading for the nearest curry shop. Wigan Casino closed in the late 70s, by which time the scene was shifting to the Mecca in Blackpool. The mid seventies were not kind to the old English seaside resorts but the Northern Soul scene offered some relief. The large halls where grandparents had danced in Larkin’s 1914 became venues for large-scale soul events. Never such innocence indeed! And appropriately, it was at one of these places where a veritable Great War erupted in Northern Soul.

Wigan Casino closed in the late 70s, by which time the scene was shifting to the Mecca in Blackpool. The mid seventies were not kind to the old English seaside resorts but the Northern Soul scene offered some relief. The large halls where grandparents had danced in Larkin’s 1914 became venues for large-scale soul events. Never such innocence indeed! And appropriately, it was at one of these places where a veritable Great War erupted in Northern Soul. Its longevity is not really such a great mystery. The music is timeless and brilliant. A legendary Northern Soul standard like Gloria Jones’ Tainted Love (famously covered by Soft Cell, a band made up of two Northern Soul boys from Leeds) never gets old. It’s own obscurity has helped too. I once accidentally went to a comprehensive but vacuous Jean Paul Gaultier exhibition at an art gallery. The ‘punk’ section made me cry. This is where something brilliant died, I thought. But punk’s rise was so meteoric that it was doomed from the beginning. Northern Soul, as Cosgrove points out, was completely ignored by the NME and other mainstream publications. It was too Northern, too sweaty, and altogether too provincial for London cool hunters. For some reason old Jean Paul’s Northern Soul line never appeared. Maybe it was the George Best haircuts and homemade club patches. He just couldn’t see it.

Its longevity is not really such a great mystery. The music is timeless and brilliant. A legendary Northern Soul standard like Gloria Jones’ Tainted Love (famously covered by Soft Cell, a band made up of two Northern Soul boys from Leeds) never gets old. It’s own obscurity has helped too. I once accidentally went to a comprehensive but vacuous Jean Paul Gaultier exhibition at an art gallery. The ‘punk’ section made me cry. This is where something brilliant died, I thought. But punk’s rise was so meteoric that it was doomed from the beginning. Northern Soul, as Cosgrove points out, was completely ignored by the NME and other mainstream publications. It was too Northern, too sweaty, and altogether too provincial for London cool hunters. For some reason old Jean Paul’s Northern Soul line never appeared. Maybe it was the George Best haircuts and homemade club patches. He just couldn’t see it. I liked the people in Young Soul Rebels too. Northern Soul was always about individuals as much as it was about music. Many of the participants he introduces to the reader are working class English folk living in the slowly fading light of the industrial revolution. Northern Soul provided an identity and a community at a time when both were under serious threat from the forces of globalization and Thatcherite economics. There is the sad story of his friend Pete Lawson who struggles with mental illness and drug addiction while finding relief in record collecting. There is the surreal tale of master bootlegger, Simon Soussan, a figure out of Le Carre. Their stories, along with the frequently hilarious antics of various DJs, collectors, and dancers all build a vivid picture of the Northern Soul scene and northern England in the 70s and 80s. Martha Graham once said that ‘dancing is the hidden language of the soul of the body’. Cosgrove reveals a bit of the secret language of Northern soul in this worthy book.

I liked the people in Young Soul Rebels too. Northern Soul was always about individuals as much as it was about music. Many of the participants he introduces to the reader are working class English folk living in the slowly fading light of the industrial revolution. Northern Soul provided an identity and a community at a time when both were under serious threat from the forces of globalization and Thatcherite economics. There is the sad story of his friend Pete Lawson who struggles with mental illness and drug addiction while finding relief in record collecting. There is the surreal tale of master bootlegger, Simon Soussan, a figure out of Le Carre. Their stories, along with the frequently hilarious antics of various DJs, collectors, and dancers all build a vivid picture of the Northern Soul scene and northern England in the 70s and 80s. Martha Graham once said that ‘dancing is the hidden language of the soul of the body’. Cosgrove reveals a bit of the secret language of Northern soul in this worthy book. Detroit 67: The Year That Changed Soul Stuart Cosgrove, 2015

Detroit 67: The Year That Changed Soul Stuart Cosgrove, 2015 Detroit 67 begins with a long section outlining the day to day activities and troubled internal relations of The Supremes. The Motown gossip is here – yes, Berry Gordy was involved with Diana Ross – but the focus is on Florence Ballard who will, in Cosgrove’s account come to embody, not only the move by Motown Records towards a more corporate model, but also the decline of Detroit itself. The story then shifts rather abruptly to John Sinclair and the beginnings of the MC5. The connection, at first, seems tenuous. Sinclair hated Motown, though he had once shopped in Gordy’s unsuccessful record store for obscure jazz sides. The MC5 were about as far removed from The Supremes as would be possible in one city.

Detroit 67 begins with a long section outlining the day to day activities and troubled internal relations of The Supremes. The Motown gossip is here – yes, Berry Gordy was involved with Diana Ross – but the focus is on Florence Ballard who will, in Cosgrove’s account come to embody, not only the move by Motown Records towards a more corporate model, but also the decline of Detroit itself. The story then shifts rather abruptly to John Sinclair and the beginnings of the MC5. The connection, at first, seems tenuous. Sinclair hated Motown, though he had once shopped in Gordy’s unsuccessful record store for obscure jazz sides. The MC5 were about as far removed from The Supremes as would be possible in one city.

“It Takes Two” Diana Ross and Rob Tyner

“It Takes Two” Diana Ross and Rob Tyner