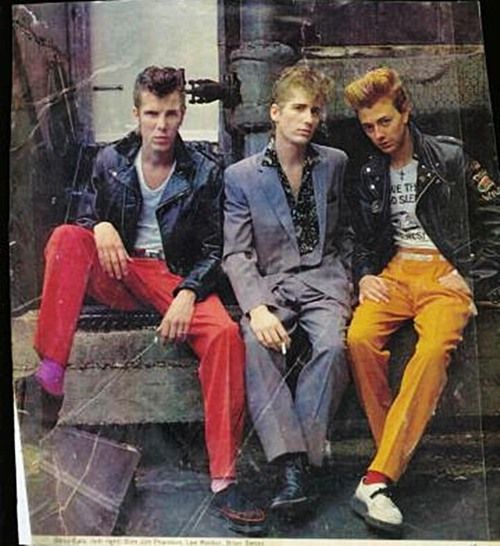

A Stray Cat Struts: My Life as a Rockabilly Rebel by Slim Jim Phantom, Thomas Dunne, 2016

A Stray Cat Struts: My Life as a Rockabilly Rebel by Slim Jim Phantom, Thomas Dunne, 2016

In his memoir A Stray Cat Struts: My Life as a Rockabilly Rebel, Slim Jim Phantom, the drummer in the Stray Cats, makes the following observation: “There were quite a few rock guys in our school and neighboring town who could play faster and harder than I could. None of them had any fashion sense…”

Black slacks. Blue suede shoes. Put your cat clothes on. Flat top cats and dungaree dolls. Clothes are a big deal in the music Slim Jim plays.

Rockabilly is perhaps the most enduring of all rock and roll subcultures. Its origins are murky and earlier than generally thought. The name, a portmanteau of rock and hillbilly, suggests something that might sound like Workingman’s Dead or The Gilded Palace of Sin. Of course rockabilly sounds nothing like either of those records.

I’m happy to argue (you buy the drinks – I’ll talk) but I think rockabilly began in 1927 with Jimmie Rodgers. His first Blue Yodel, better known as T for Texas, has crept into the repertoire of many a rockabilly band for good reason. It has all the basic elements. It’s an up-tempo blues sung like a country song. A number of Rodgers’ subsequent hits have the same quality. But the key moment for rockabilly and American music in general might be the day in 1930 when he sat down with Louis Armstrong and recorded Blue Yodel Number 9. Number 9. Number 9…

Cool Cat Jimmie Rodgers

Louis Armstrong’s records with the Hot Five and Hot Seven are as eclectic as they are brilliant. Yes, he is laying the foundations of jazz but that foundation also supports swing, jump blues, and rock and roll. The fact that he and Jimmie Rodgers could hear the symbiosis in their work is significant because the next important chapter in the rockabilly story belongs to Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys.

Western Swing as played in the 1930s by Bob Wills, Spade Cooley, The Light Crust Doughboys, and Milton Brown represents a rich period in American music. It’s swing played on strings. The cowboy hats and corny lyrics are deceptive because this is jazz. And it is why rockabilly doesn’t sound like New Riders of the Purple Sage. There is a jazz sensibility in early rock and roll that stretches back to Lindy Hoppers of 1930s and Cab Calloway at his most frantic. When Sam Philips made his questionable assertion that he could make a million dollars if only he could find a white man who sang like a black man, he might have had someone like Nat King Cole in mind. Elvis – and perhaps more importantly, Scotty Moore and Bill Black were channeling something else that day at Sun Studios. They were playing blues but they were playing it the way jazz artists play it. They were swinging it around, slowing it down, speeding it up. Listen carefully to the ‘Sun Sessions’ and you can hear the whole history of American music. In rock journalese, Louis Jordan meets Hank Williams, Lionel Hampton jams with Gene Autry with T-Bone Walker on guitar. Or something like that.

Rockabilly never went away either. Very few people heard it outside of the south in the first place but, as someone once said of the Velvet Underground, everyone who did formed a band. A slight exaggeration perhaps – but certainly all of The Beatles held this genre in high regard. They covered a lot of rockabilly songs. Watch the Let It Be film. When the going got tough, the tough jammed on Carl Perkins’ numbers.

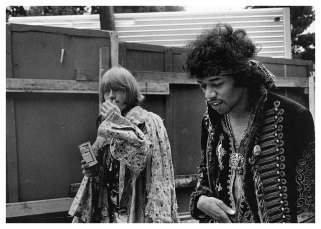

But they weren’t alone. As Slim Jim Phantom notes in his memoir, Blind Faith covered one of Buddy Holly’s most smoking tunes in Well Alright and The Who did Summertime Blues. CCR, the biggest selling band of the late sixties, were a rockabilly band, no more and no less. Their blues excursions aren’t a patch on their rockabilly moments. Jimmy Page is a better at rockabilly than blues and so is Keith Richards. They might talk about Buddy Guy but their best moments say Cliff Gallop, in Page’s case, and Chuck Berry in Richards’. Head Stray Cat Brian Setzer said that when he first met Keith, the guitarist picked up an old Gretsch and played a letter perfect version of Elvis’ Baby Let’s Play House. Setzer later became one of Robert Plant’s many Page stand-ins in The Honeydrippers. Many of the great guitarists of the 60s and 70s started out playing this kind of music. Robbie Robertson, Jimi Hendrix, Richie Blackmore, Alvin Lee, and Jeff Beck all began as twangy sidemen. Even Robert Fripp started out playing in a band called The Ravens. Robert Fripp! I’ve always maintained that Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited is essentially a rockabilly record and he seems to drift back to the genre regularly. Listen to Dirt Road Blues on Time Out of Mind.

Dylan, The Beatles, The Stones, and Led Zeppelin. Rockabilly is the secret hero of Rock and Roll’s many stanza’d Howl.

Which brings me to The Stray Cats, a band featuring vocalist and twangmaster Brian Setzer and ably rhythm sectioned by his Long Island high school chums Lee Rocker and our author, Slim Jim Phantom.

Which brings me to The Stray Cats, a band featuring vocalist and twangmaster Brian Setzer and ably rhythm sectioned by his Long Island high school chums Lee Rocker and our author, Slim Jim Phantom.

Slim Jim (real name James McConnell), Lee Rocker (Drucker) and Brian Setzer came together as teenagers with a mutual interest in rockabilly. They were all playing in other bands. The side project, as so often happens, began to attract attention and the other bands disappeared. It’s Slim Jim’s book but Brian Setzer was part of a late 70s New York new wave band called The Bloodless Pharaohs. You can probably download a box set and footage of every show they ever did now but in the 80s I found one of their songs on a compilation album and did a victory lap around a record store. They’re not mentioned in this book. Slim Jim, it must be said, has a big heart but little interest in that sort of detail.

Slim Jim’s implied and occasionally stated assertion that The Stray Cats single handedly revived rockabilly doesn’t hold up. It wasn’t part of the music mainstream in America in 1980 but it wasn’t a non-entity either. Slim Jim and the boys might have got something happening in Long Island but The Blasters were weathering gigs with Black Flag in California in the late 70s. A ferry ride away in NYC, Robert Gordon had already recorded two absolutely stellar rockabilly revival records by the time Slim Jim bought his first jar of Royal Crown.

Over in England, rockabilly was alive and well. The Shakin’ Pyramids’ sizzling debut, Skin ‘Em Up, appeared a year before The Stray Cats’ first English record. You can laugh about Shakin’ Stevens but there is some great rockabilly on his first couple of albums. Matchbox is not much remembered these days but they released their first album in 1976 and scored a big hit with the classic Rockabilly Rebel in 1979. The Stray Cats are easily the most successful revival band but they are only part of the story. Slim Jim doesn’t mention it but the whole reason they left the cozy club scene of Long Island for London was to join a movement already in play.

But this isn’t to slight Slim Jim or his book. The Stray Cats were the real deal and, to be honest, better musicians than most of the English revival guys. The competition was a bit stiffer in the States. While they never enjoyed anywhere near the success, The Blasters and The Paladins were hard to top.

But back to Slim Jim. He is probably best on the early years. The memoir hops around a bit but the basic story of their move to England and the space they found within the immediate post punk scene is of great interest. Rockabilly always seemed to be just below the surface in early English punk. Malcolm McLaren had run a shop for Teddy Boys called Let It Rock on the King’s Road before changing the name to Sex and, well, you know the rest. The Sex Pistols recorded a couple of Eddie Cochran songs. The Clash looked like a rockabilly band for a while. Billy Idol sang about a club blasting out ‘maximum rockabilly’ in Generation X’s Kiss Me Deadly. Tom Petty noted that “rockabilly music was in the air” in King’s Road on the Hard Promises album. The Stray Cats arrived in a city ready for their look and their sound. They somehow skirted the slightly moldy atmosphere of, say, The Polecats, and became a band most people could agree on.

Remarkably, ‘most people’ included not one but all of The Rolling Stones. In 1980, Keith and Mick could hardly bear to be on stage together but they turned up with the rest of the band one night to see The Stray Cats open a show in a crummy London pub. The idea was that they would sign with Rolling Stone Records and that Mick and Keith would produce their first album together. Like that was ever going to happen! It didn’t but they did do a series of dates opening for the old boys in America. Bill Wyman was still in the band then and he was, and is, a rockabilly fanatic. Remember the Willie and Poorboys album? A little overproduced but full of heart. Slim Jim played on the b side of a single apparently.

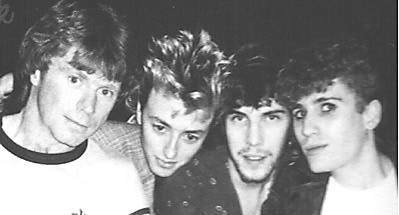

with Dave Edmunds

The Stray Cats ended up on Arista Records in the capable hands of Dave Edmunds who produced all of their best work. Edmunds is a rockabilly legend who scored a hit in the late 60s as part of Love Sculpture with an instrumental called Sabre Dance. He then went solo in 1972 with a stunning rockabilly album called Rockpile, not to be confused with the band he later formed with Nick Lowe. There was no one better qualified to produce The Stray Cats and the album was a great success in England. Songs like Runaway Boys and Rumble In Brighton became big hits there but the band were still virtually unknown in America.

Luckily, MTV had just appeared and, come the moment, come the band. The Stray Cats looked cool. All of them, all the time. The clothes were vaguely 50s style with some Ted additions and a punk overlay that made them look somehow contemporary. MTV was perfect for them. TV in general worked pretty well for the Stray Cats and an early appearance on a now forgotten show called Fridays made them stars in the States.

There was a lot going on in the early 80s. The music industry was enjoying the last few years of prosperity before everything went shit-shaped in the late 90s. There was a lot of money and, it would seem from Slim Jim’s account, a lot of cocaine. The period has a more or less deserved reputation for excess and overproduction but the sheer size of the industry had some benefits. There was room for a band like The Stray Cats in among Madonna, U2, Bruce Springsteen, and the other superstars of the period.

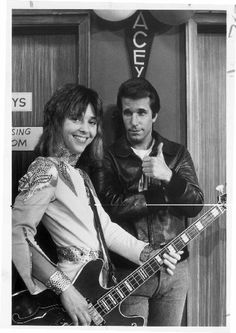

With Britt on an unusually bad hair day for our hero.

Their moment, however, was brief and no sooner is Slim Jim married to Britt Eckland and walking his dogs in Hollywood than the band is making its last album. Interesting stuff but the timeline in this book is very difficult to follow. Slim Jim will note that he has been sober for five years on one page and then be found having a bump of coke with Lemmy on the next. Either Slim Jim simply told the stories as they come to him or the book was ghost written by Peter Hoeg. Probably the former.

His post Stray Cats life has been slightly less exalted but no less busy. He appeared in Clint Eastwood’s Bird, remembering his co star Forest Whittaker as ‘the guy in Fast Times’. Yeah, I’d forgotten he was in that too. He also tells a hilarious story of an incident that took place while he was filming one of his two scenes. I won’t spoil it but it involves a very angry Clint Eastwood.

He opened a bar and music venue called The Cat in Hollywood, toured and recorded with a dizzying number of other bands, got back together with The Stray Cats, broke up with them again. He was here in Melbourne last Thursday. Slim Jim still gets around.

What does one say about a memoir like this one? It’s a bit of mess in terms of chronology and anyone looking for a detailed account of The Stray Cats’ career will want to look elsewhere. In fact, there’s not much about The Stray Cats at all. I would have been very curious to hear about the recording of those early albums and what it was like to work with Dave Edmunds. Perhaps Brian Setzer will cover that if he ever writes a book. There is a bit about their sound but never enough to really satisfy. Just when you think he is about to double down on the band that made him famous, he’s back in a club with Michael J Fox or someone.

What does one say about a memoir like this one? It’s a bit of mess in terms of chronology and anyone looking for a detailed account of The Stray Cats’ career will want to look elsewhere. In fact, there’s not much about The Stray Cats at all. I would have been very curious to hear about the recording of those early albums and what it was like to work with Dave Edmunds. Perhaps Brian Setzer will cover that if he ever writes a book. There is a bit about their sound but never enough to really satisfy. Just when you think he is about to double down on the band that made him famous, he’s back in a club with Michael J Fox or someone.

But this is not a book without merit. For one thing, Peter Hoeg notwithstanding, I am convinced that he wrote it. That might sound silly – his name is on the cover – but, as I have said before, I doubt that a lot of these rock and roll memoirs are written (or even read) by their subjects. I could name three very recent and notable examples but I’ll be kind. For now! This is most definitely Slim Jim Phantom and if you fancy an evening with a guy who has had a remarkable life that has brought him into contact with the cream of rock and roll, blues, and beyond, this book is worth reading. It is also frequently funny as hell. Michael Jackson appears out of nowhere with Elizabeth Taylor in tow and whispers to Slim Jim, ‘I really like that song about the cat.’ Our hero ends up in the dark with Jerry Lee Lewis and a groupie. Keith Richards throws everyone out of his dressing room while Slim Jim is in the toilet. The drummer has to come out and face the enraged Stone who sits him down and feeds him narcotics. Clothes are a big number in this book if male rock and roll style is your thing. Slim Jim always tells us what people were wearing and details the evolution of his own look. Much is made, for example, of a polka dot scarf that he receives from Keith Richards in a trade. Without giving too much away, Britt is annoyed because Slim Jim ends up with a tatty cotton affair while Keith gets a silk one from her collection.

So Slim Jim Phantom leaves us with a memoir that won’t trouble the Pulitzer folks but might improve your spirits on a long flight or a rainy day at home. You might even find yourself hauling Rant n’ Rave out of an old crate for another spin. Meanwhile another rockabilly revival is either imminent or underway. In the immortal words of Joe Clay, ‘don’t mess with my ducktail.’

Teasers: Slim Jim’s Rules of Rock and Roll are a highlight. Number Four is: “Always wear something around your waist that has nothing to do with holding your pants up.” Noted!

Teasers: Slim Jim’s Rules of Rock and Roll are a highlight. Number Four is: “Always wear something around your waist that has nothing to do with holding your pants up.” Noted!

This TV appearance launched them in America. Still gives me chills:

Dave Edmunds and The Stray Cats:

Jimmie and Satchmo:

I don’t really understand the concept of comfort food. Nothing that requires a trip to the supermarket and/or actual cooking could provide me with any real comfort. However, I do have some sense of what it might mean in terms of a musical diet. I’m not talking about ‘guilty pleasures’ here. I never feel guilty about the music I like. This is macaroni and cheese music, reliable old stuff that doesn’t challenge but does satisfy. It might not change your life but it reminds you of just how good it can be.

I don’t really understand the concept of comfort food. Nothing that requires a trip to the supermarket and/or actual cooking could provide me with any real comfort. However, I do have some sense of what it might mean in terms of a musical diet. I’m not talking about ‘guilty pleasures’ here. I never feel guilty about the music I like. This is macaroni and cheese music, reliable old stuff that doesn’t challenge but does satisfy. It might not change your life but it reminds you of just how good it can be. This is, arguably, the first major study of the genre. There are other books on the subject. Philip Auslander’s Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Pop Music is a thoughtful take on it and Dandies in the Underworld by Alwyn Turner is an informative, if brief, account too. However, the Simon Reynolds treatment is of another order altogether. He has previously written on hip hop, nostalgia, post punk, and rave. He is not simply a fan with flare. All of his work mixes critical theory with extensive research. This isn’t rock and roll, this is serious!

This is, arguably, the first major study of the genre. There are other books on the subject. Philip Auslander’s Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Pop Music is a thoughtful take on it and Dandies in the Underworld by Alwyn Turner is an informative, if brief, account too. However, the Simon Reynolds treatment is of another order altogether. He has previously written on hip hop, nostalgia, post punk, and rave. He is not simply a fan with flare. All of his work mixes critical theory with extensive research. This isn’t rock and roll, this is serious!

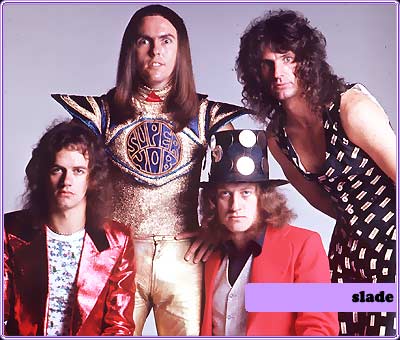

Similarly in Shock and Awe, Reynolds sees glam as part of a long tradition that stretches back to old Hollywood and reaches up to Lady Gaga. I don’t dispute this but, for me, it’s the killer riffs and the sheer three chord fun of it that makes it my comfort music. Slade, who Reynolds rightly suggests have been unfairly forgotten, are wonderful purveyors of power pop. They don’t have to be anything more. The Sweet are The Monkees of glam but at their best are a joyful reminder of good times and warm summer evenings.

Similarly in Shock and Awe, Reynolds sees glam as part of a long tradition that stretches back to old Hollywood and reaches up to Lady Gaga. I don’t dispute this but, for me, it’s the killer riffs and the sheer three chord fun of it that makes it my comfort music. Slade, who Reynolds rightly suggests have been unfairly forgotten, are wonderful purveyors of power pop. They don’t have to be anything more. The Sweet are The Monkees of glam but at their best are a joyful reminder of good times and warm summer evenings. The Sun and The Moon and the Rolling Stones by Rich Cohen, Spiegel and Grau, 2016

The Sun and The Moon and the Rolling Stones by Rich Cohen, Spiegel and Grau, 2016 A book about The Rolling Stones presents something of a quandary to both writer and reader. What does one say about this band that isn’t already part of one of the great Rock and Roll myth cycles. The Stones were badass compared to The Beatles? The Sixties ended at Altamont during Under My Thumb? Exile on Main St was badly reviewed at the time (it really wasn’t – check for yourself) but is the greatest record ever made? There are almost as many books about the Stones as there are on The Beatles. This formidable library now includes Keith’s bestselling autobiography Life. Mick Jagger tells Cohen that Richards didn’t write it and probably hasn’t read it either. I wasn’t crazy about Life, to be honest, and this made me laugh out loud, as the kids say.

A book about The Rolling Stones presents something of a quandary to both writer and reader. What does one say about this band that isn’t already part of one of the great Rock and Roll myth cycles. The Stones were badass compared to The Beatles? The Sixties ended at Altamont during Under My Thumb? Exile on Main St was badly reviewed at the time (it really wasn’t – check for yourself) but is the greatest record ever made? There are almost as many books about the Stones as there are on The Beatles. This formidable library now includes Keith’s bestselling autobiography Life. Mick Jagger tells Cohen that Richards didn’t write it and probably hasn’t read it either. I wasn’t crazy about Life, to be honest, and this made me laugh out loud, as the kids say.

Under the Big Black Sun: A Personal History of LA Punk, John Doe with Tom DeSavia and Friends, De Capo 2016

Under the Big Black Sun: A Personal History of LA Punk, John Doe with Tom DeSavia and Friends, De Capo 2016 So this is an unfamiliar LA, a city of derelict apartment blocks filled with misfits who are making films, writing poetry, and forming bands like The Go Gos. It’s a night place where a bunch of disaffected kids come together and try something different. All of them had grown up in the Watergate 1970s and the slow death of the 60s dream. Like their counterparts in New York, London, Sydney, and Toronto, they weren’t interested in the bloated rock music on the radio so they made it new. Henry Rollins says that history is filled with moments where someone stands up and says ‘Fuck this. No seriously, fuck this.’ This is what happened in LA in 1977.

So this is an unfamiliar LA, a city of derelict apartment blocks filled with misfits who are making films, writing poetry, and forming bands like The Go Gos. It’s a night place where a bunch of disaffected kids come together and try something different. All of them had grown up in the Watergate 1970s and the slow death of the 60s dream. Like their counterparts in New York, London, Sydney, and Toronto, they weren’t interested in the bloated rock music on the radio so they made it new. Henry Rollins says that history is filled with moments where someone stands up and says ‘Fuck this. No seriously, fuck this.’ This is what happened in LA in 1977. Punk began in LA as the music of the outsider. There is a fine essay by Teresa Covarraubias of the band The Brat, about the scene in East LA and the contribution of Latino bands like The Plugz – who once backed Bob Dylan on Letterman. Yes, Los Lobos makes an appearance here. They once opened for PIL. What happened? Guess. It involves saliva. Her essay ends, however, on a sad note about the night that a local hall, The Vex, was destroyed by the violent suburban punks who began to dominate the scene in the early 80s. They were, for the most part, white and male. The diversity of the early scene didn’t last long. When the bullyboy skins from Orange Country turned up, women too drifted away from what had been a remarkably progressive moment in rock and roll.

Punk began in LA as the music of the outsider. There is a fine essay by Teresa Covarraubias of the band The Brat, about the scene in East LA and the contribution of Latino bands like The Plugz – who once backed Bob Dylan on Letterman. Yes, Los Lobos makes an appearance here. They once opened for PIL. What happened? Guess. It involves saliva. Her essay ends, however, on a sad note about the night that a local hall, The Vex, was destroyed by the violent suburban punks who began to dominate the scene in the early 80s. They were, for the most part, white and male. The diversity of the early scene didn’t last long. When the bullyboy skins from Orange Country turned up, women too drifted away from what had been a remarkably progressive moment in rock and roll. 1966: The Year the Decade Exploded, Jon Savage, Faber and Faber 2015

1966: The Year the Decade Exploded, Jon Savage, Faber and Faber 2015 At the moment on my coffee table, there are books called 1607 (James Shapiro’s follow up to 1599), 1966, Detroit 67, and a novel by Garth Risk Hallberg called City on Fire which appears to be set entirely in 1977 although it’s 900 pages long and I’m only halfway through it. It might be 1979 when I finish. Or 2017. On my kobo, there is a book by David Browne called Fire and Rain that is all about 1970 and one from a few years ago called 1968 by Mark Kurlansky. They are all of interest but when ‘1996’ appears, don’t expect a review. I didn’t like anything about that whole decade.

At the moment on my coffee table, there are books called 1607 (James Shapiro’s follow up to 1599), 1966, Detroit 67, and a novel by Garth Risk Hallberg called City on Fire which appears to be set entirely in 1977 although it’s 900 pages long and I’m only halfway through it. It might be 1979 when I finish. Or 2017. On my kobo, there is a book by David Browne called Fire and Rain that is all about 1970 and one from a few years ago called 1968 by Mark Kurlansky. They are all of interest but when ‘1996’ appears, don’t expect a review. I didn’t like anything about that whole decade.

Some of these chapters are more convincing than others. His evocation of homosexuality in 1966 is particularly well done. The Tornados ‘Do you come here often?’, is widely thought of as the first ‘gay’ pop song – for those who missed the subtext of Tutti Frutti and countless other 1950s singles. Joe Meek, the legendary producer of this song, had begun his long slide into the madness that would end in his death in 1967. Like Brian Epstein, he led a secret life and had been subjected to arrest and blackmail attempts over the years. The laws were changing but it was still a difficult time to be gay in England. The chapter also picks up the story of San Francisco in that year. The Gay rights movement, in most people’s minds, begins with Stonewall in 1969 but Savage shows that it was already crystalising in 1966.

Some of these chapters are more convincing than others. His evocation of homosexuality in 1966 is particularly well done. The Tornados ‘Do you come here often?’, is widely thought of as the first ‘gay’ pop song – for those who missed the subtext of Tutti Frutti and countless other 1950s singles. Joe Meek, the legendary producer of this song, had begun his long slide into the madness that would end in his death in 1967. Like Brian Epstein, he led a secret life and had been subjected to arrest and blackmail attempts over the years. The laws were changing but it was still a difficult time to be gay in England. The chapter also picks up the story of San Francisco in that year. The Gay rights movement, in most people’s minds, begins with Stonewall in 1969 but Savage shows that it was already crystalising in 1966. ‘global village’ by 1966 and most of the events in the UK and US were mirrored in other places. Others may be able to point to music related events in Africa or even the Middle East. Please point!

‘global village’ by 1966 and most of the events in the UK and US were mirrored in other places. Others may be able to point to music related events in Africa or even the Middle East. Please point! Lives of the Poets (with Guitars): Thirteen Outsiders Who Changed Modern Music Ray Robertson, Biblioasis 2016

Lives of the Poets (with Guitars): Thirteen Outsiders Who Changed Modern Music Ray Robertson, Biblioasis 2016 Many novelists attempt this trick. Not many get there. Novels about rock and roll bands usually fall in a great big heap when the writer tries to describe the music. I’m happy to be corrected on this one. Please drench me in the names of credible rock and roll novels. I can think of three. The Doubleman is one, Paul Quarrington’s Whale Music is another. The final and greatest of all is Ray Robertson’s 2002 novel, Moody Food.

Many novelists attempt this trick. Not many get there. Novels about rock and roll bands usually fall in a great big heap when the writer tries to describe the music. I’m happy to be corrected on this one. Please drench me in the names of credible rock and roll novels. I can think of three. The Doubleman is one, Paul Quarrington’s Whale Music is another. The final and greatest of all is Ray Robertson’s 2002 novel, Moody Food. The first essay on Gene Clark sets the tone (and the volume, ha ha!). Clark is a notable cult figure. His album No Other can sit comfortably next to a whole bunch of other ambitious and brilliant albums that were completely ignored when they appeared. Clark’s sad tale is a staple of magazines like MOJO and Uncut but Ray tells it in such an affecting manner that it felt as though I was reading it for the first time. This musician’s musical journey was an unusual one that spanned several decades. Ray uses his considerable storytelling abilities to give his music a cohesive frame. This would be insupportable if the music wasn’t described with such clarity and detail. I could hear these albums as I read. That’s impressive.

The first essay on Gene Clark sets the tone (and the volume, ha ha!). Clark is a notable cult figure. His album No Other can sit comfortably next to a whole bunch of other ambitious and brilliant albums that were completely ignored when they appeared. Clark’s sad tale is a staple of magazines like MOJO and Uncut but Ray tells it in such an affecting manner that it felt as though I was reading it for the first time. This musician’s musical journey was an unusual one that spanned several decades. Ray uses his considerable storytelling abilities to give his music a cohesive frame. This would be insupportable if the music wasn’t described with such clarity and detail. I could hear these albums as I read. That’s impressive.

Detroit 67: The Year That Changed Soul Stuart Cosgrove, 2015

Detroit 67: The Year That Changed Soul Stuart Cosgrove, 2015 Detroit 67 begins with a long section outlining the day to day activities and troubled internal relations of The Supremes. The Motown gossip is here – yes, Berry Gordy was involved with Diana Ross – but the focus is on Florence Ballard who will, in Cosgrove’s account come to embody, not only the move by Motown Records towards a more corporate model, but also the decline of Detroit itself. The story then shifts rather abruptly to John Sinclair and the beginnings of the MC5. The connection, at first, seems tenuous. Sinclair hated Motown, though he had once shopped in Gordy’s unsuccessful record store for obscure jazz sides. The MC5 were about as far removed from The Supremes as would be possible in one city.

Detroit 67 begins with a long section outlining the day to day activities and troubled internal relations of The Supremes. The Motown gossip is here – yes, Berry Gordy was involved with Diana Ross – but the focus is on Florence Ballard who will, in Cosgrove’s account come to embody, not only the move by Motown Records towards a more corporate model, but also the decline of Detroit itself. The story then shifts rather abruptly to John Sinclair and the beginnings of the MC5. The connection, at first, seems tenuous. Sinclair hated Motown, though he had once shopped in Gordy’s unsuccessful record store for obscure jazz sides. The MC5 were about as far removed from The Supremes as would be possible in one city.

“It Takes Two” Diana Ross and Rob Tyner

“It Takes Two” Diana Ross and Rob Tyner

Small Town Talk by Barney Hoskyns, Da Capo Press 2016

Small Town Talk by Barney Hoskyns, Da Capo Press 2016

He thought that she was something truly special. And he was right! Anyone else noticed that Janis seems to be out of fashion at the moment? What’s that about?

He thought that she was something truly special. And he was right! Anyone else noticed that Janis seems to be out of fashion at the moment? What’s that about?