Woman* Walk The Line: How the Women in Country Music Changed Our Lives by Holly Gleason (editor), University of Texas Press 2017

Woman* Walk The Line: How the Women in Country Music Changed Our Lives by Holly Gleason (editor), University of Texas Press 2017

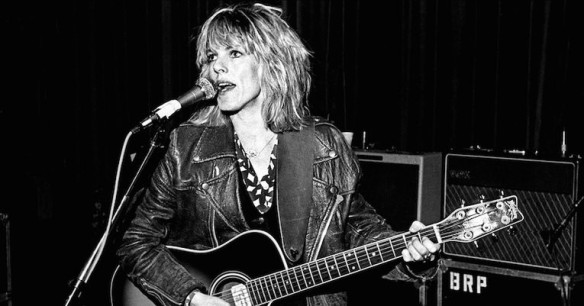

It is 1987. Lucinda Williams sits at the bar of the Palomino Club in North Hollywood. Jim Lauderdale and Buddy Miller are there too, swapping tour stories nearby, while Candeye Kane sets up on stage. What a picture. I feel like I’ve waited years to catch a glimpse like this of Lucinda Williams. No one has ever written a serious biography or a book about her music. The feature articles I’ve read over the years have, predictably, focused on her personal life and her reputation as ‘difficult’ in the studio. If that’s true, I hope she stays difficult because her last few albums have been these remarkably spare but utterly evocative dreamscapes. I can maybe think of three other records in my collection that match Ghosts of Highway 20 for atmosphere. Time Out of Mind, maybe? On The Beach? Kind of Blue?

‘Difficult’ sounds like what happens when a musician who happens to be a woman demands that her record sounds like what she hears in her head. Imagine how ‘difficult’ the three artists behind the albums above were during the recording sessions. The normally arch-mellow Daniel Lanois smashed a dobro in frustration after a day of dealing with Bob Dylan during the Time Out of Mind sessions in New Orleans. Bob really is difficult in the studio and this is well known. But it’s not the important part of the story, is it? Lucinda Williams is, for my money, creating better music than just about anyone on the planet at the moment. She is a gifted writer, a brilliant performer, and her albums get better and better. Why isn’t she on the cover of those rock magazines so beloved of men my age? Look at the credits for Where The Spirit Meets The Bone. Tony Joe White, Bill Frisell, Ian McLagan for heaven’s sake. It’s a MOJO reader’s wet dream!

The answer is pretty clear. A cover story featuring Bob or The Beatles will sell, cover stories about women do not, apparently. It’s depressing but true. Despite the pioneering efforts of writers like Lillian Roxon and Ellen Willis, writing on popular music is still dominated by, if not actual men, a male aesthetic around what is valuable in rock and roll, blues, country, and so on.

Lucinda Williams

The image of Lucinda in the Palomino comes from a new book called Woman Walk The Line: How the Women in Country Music Changed Our Lives. It’s a collection of personal essays curated and edited by Holly Gleason, a journalist and songwriter in her own right. I will confess that I only picked it up because I noticed that there was a piece about Lucinda written by Holly herself. But when I scanned the table of contents, I was intrigued. Lil Hardin? Wanda Jackson? Rita Coolidge? Sure, Dolly, Loretta, and Barbara Mandrell are in there but you’ll be surprised by the list. KD Lang but no Patsy Cline? Okay, but wait a minute: What’s Lil Hardin doing in there?

Louis and Lil

Lil was the second Mrs Louis Armstrong but more significantly, she was an important early jazz piano player and a songwriter who wrote ‘Just For A Thrill’ – a hit for Ray Charles, Louis’s ‘Struttin’ with Some BBQ’, and ‘Bad Boy – recorded by Ringo, Mink Deville and others. She was also a key member of the game-changing Hot Five band led by Louis. Her connection to Country music might seem tenuous though she did play piano on Jimmie Rogers’ Blue Yodel No. 9. The author of the essay, Alice Randall, is a novelist and songwriter who grew up in Detroit in the 60s. She explains why Lil Hardin appealed to her more than the obvious stars of her hometown – Diana Ross et al. Randall was the first African American woman to write a number one country song – Trisha Yearwood’s ‘XXXs and OOOs’. She calls Lil a trailblazer and makes a very convincing case for a musician who should be far better known.

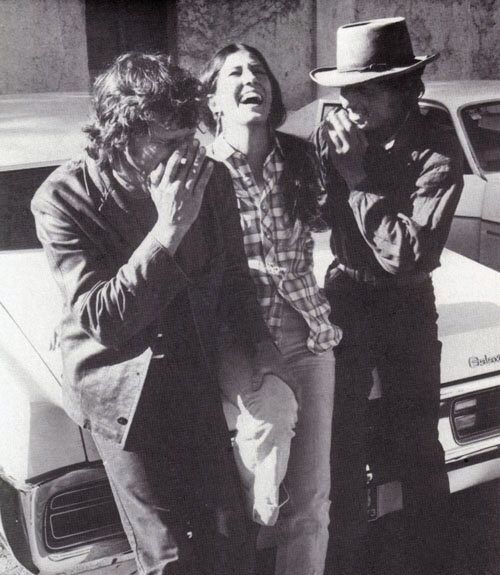

A similar though very different essay later in the book comes from Kandia Crazy Horse, a songwriter and musician, who relates deeply to Rita Coolidge on the basis of their shared Cherokee background. Coolidge is another woman who doesn’t appear in MOJO often enough despite her association with Joe Cocker, Leon Russell, Hendrix, and many others, besides her one time husband, Kris Kristofferson. Kandia Crazy Horse’s vision of rock and roll history led her to name her first album Stampede (Buffalo Springfield fans will get this reference) and reconfigure the late 60s story so that Native American musicians are given their due and recognized for their heritage. Jimi Hendrix is well known to have Native ancestry but what about Ronnie Spector? I didn’t know that!

‘Clowns to the left of me, jokers to the right’. Rita Coolidge stuck in the middle.

The second half of the book deals with more recent artists and will probably appeal more to country fans who are better acquainted with artists like Terri Clark and Kasey Musgraves. That said, none of these pieces is without some interest for the general reader. A collection of essays that simply made the point that the music business is difficult for women would be redundant. It’s pretty clear now that Hollywood is hell on earth for female actors and corporate life probably isn’t any easier. The music business has always been a nasty place generally but always much worse for women. Country music seems like a genre where women have always had more or less equal billing – compared to say, Prog Rock – but it’s complicated. Tyler Mahan Coe’s podcast, Cocaine and Rhinestones, is an excellent corrective here. Listen to the episodes on Loretta Lynn and Jeannie C. Riley. Find out what happened to Garth Brooks when he presented TNT with a music video depicting an abused wife fighting back. Banned! Truly.

Kandia Crazy Horse

This collection doesn’t shy away from pointing out the hypocrisy and the often blatant sexism at work in the music industry but there is more here than a series of polemics. The real theme of the collection is inspiration. Reading through, I was struck over and over by the impact music can have in people’s lives. Ronni Lundy’s essay on Hazel Dickens outlines Lundy’s own startling journey and the way in which Dickens’ music turned up at key moments. She didn’t find the music, the music found her. It is something that many of these writers come back to in this book. I don’t have much interest in The Judds but I was struck by Courtney E. Smith’s story of how she bought their Greatest Hits cassette on a school visit to New York and fell asleep listening it every night of the trip. I have similar stories and so do you. It’s that sort of book and one well worth reading even if country music isn’t your thing.

Meanwhile, I happened to read yesterday that Lucinda is at work on a memoir. Stay tuned!

*To Grammar Enthusiasts: It is indeed Woman and not Women in the title. At first I thought it was a sly reference to Mary Wollstonecraft’s ‘Rights of Woman’ but it is, in fact, the title of an Emmylou Harris song.

Teasers: Taylor Swift’s high school essay about Brenda Lee – more interesting than you might expect! Tanya Tucker as disruptive punk rock force – a convincing case! And some good reasons why Linda Ronstadt is cool.

Roots, Radicals and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World by Billy Bragg, Faber & Faber, 2017

Roots, Radicals and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World by Billy Bragg, Faber & Faber, 2017

If you’ve never listened to skiffle, Billy presents the genre in great detail, picking out the notable from the forgettable. Ever wondered about the song ‘Maggie Mae’ on The Beatles Let It Be album? The original was the biggest hit of a Liverpool outfit called The Vipers. One of the issues for skiffle bands in the studio was the tendency for older producers to top up their sound with strings and other embellishments. The Vipers, fortunately, found a young producer who correctly noted that their rawness was part of their appeal. He simply recorded them, live on the floor. That young producer would use a similar strategy with another band from Liverpool a couple of years later. His name was George Martin.

If you’ve never listened to skiffle, Billy presents the genre in great detail, picking out the notable from the forgettable. Ever wondered about the song ‘Maggie Mae’ on The Beatles Let It Be album? The original was the biggest hit of a Liverpool outfit called The Vipers. One of the issues for skiffle bands in the studio was the tendency for older producers to top up their sound with strings and other embellishments. The Vipers, fortunately, found a young producer who correctly noted that their rawness was part of their appeal. He simply recorded them, live on the floor. That young producer would use a similar strategy with another band from Liverpool a couple of years later. His name was George Martin.

How To Listen To Jazz by Ted Gioia, Basic Books, 2016

How To Listen To Jazz by Ted Gioia, Basic Books, 2016

In the second chapter, however, he focuses on the individual musician. He uses the word ‘intentionality’ to describe the way jazz musicians approach phrasing. They mean it, man! When John Coltrane blows a note, there is nothing the least bit accidental about the manner in which it is played. It might start off quietly before rising in volume or it might be a quick blast. Same note, totally different effect. Later, in a section on pitch, Gioia tells the story of Sidney Bechet giving a saxophone lesson to a journalist in the 1940s. “I’m going to give you one note today. See how many ways you can play that note – growl it, smear it, flat it, sharp it, do anything you want to it. That’s how you express your feelings in this music. It’s like talking.” There’s Buber again.

In the second chapter, however, he focuses on the individual musician. He uses the word ‘intentionality’ to describe the way jazz musicians approach phrasing. They mean it, man! When John Coltrane blows a note, there is nothing the least bit accidental about the manner in which it is played. It might start off quietly before rising in volume or it might be a quick blast. Same note, totally different effect. Later, in a section on pitch, Gioia tells the story of Sidney Bechet giving a saxophone lesson to a journalist in the 1940s. “I’m going to give you one note today. See how many ways you can play that note – growl it, smear it, flat it, sharp it, do anything you want to it. That’s how you express your feelings in this music. It’s like talking.” There’s Buber again.

Murray Talks Music: Albert Murray on Jazz and Blues by Albert Murray and Paul Devlin (Editor), University of Minnesota Press, 2016

Murray Talks Music: Albert Murray on Jazz and Blues by Albert Murray and Paul Devlin (Editor), University of Minnesota Press, 2016 His love of jazz goes far beyond his vast knowledge of the music and its players. For Murray, jazz is the purest form of American art. Like the country itself, it is about innovation and improvisation. Jazz music, he says, is the sound of a restless nation pushing against boundaries and frontiers. It is also, for Murray, an African American art form. Some of his critics, notably Terry Teachout, have suggested that he underrated white jazz artists but Murray’s views here are far more complex. His position was that the race problem in America is one of definition and artificial lines. America for Murray was an idea, rather than a geopolitical or economic entity. He believed that African Americans were the ‘real’ Americans because they arrived from Africa with no language and no culture. They absorbed the culture of America and practiced it in its purest form, untainted by a sense of Europe as a center. They were thus able to create jazz, the greatest and perhaps only truly American art form. His first book, The Omni Americans (1970), a response to Patrick Moynihan’s damning 1965 report on the state of African Americans, suggests that the way forward could be in a redefining of American culture, to recognize the contribution of everyone involved, rather than any one group. Sadly, this probably still seems overly idealistic almost 50 years later. However, while pondering this, it occurred to me that the blues heritage of Mississippi and Chicago are now institutionalized in a manner that would have seemed unlikely even 25 years ago. When I visited Maxwell Street, Chicago, in the early 90s, the market was closed and there was no sign that this was one of the crucibles of American music. It is now heritage listed, the market has reopened, and tourism has revived what was a very depressed neighbourhood. Richard Daley’s son, of all people, made this happen! It would be lovely to think that we might one day say that music provided the groundwork for a real change in race relations in America.

His love of jazz goes far beyond his vast knowledge of the music and its players. For Murray, jazz is the purest form of American art. Like the country itself, it is about innovation and improvisation. Jazz music, he says, is the sound of a restless nation pushing against boundaries and frontiers. It is also, for Murray, an African American art form. Some of his critics, notably Terry Teachout, have suggested that he underrated white jazz artists but Murray’s views here are far more complex. His position was that the race problem in America is one of definition and artificial lines. America for Murray was an idea, rather than a geopolitical or economic entity. He believed that African Americans were the ‘real’ Americans because they arrived from Africa with no language and no culture. They absorbed the culture of America and practiced it in its purest form, untainted by a sense of Europe as a center. They were thus able to create jazz, the greatest and perhaps only truly American art form. His first book, The Omni Americans (1970), a response to Patrick Moynihan’s damning 1965 report on the state of African Americans, suggests that the way forward could be in a redefining of American culture, to recognize the contribution of everyone involved, rather than any one group. Sadly, this probably still seems overly idealistic almost 50 years later. However, while pondering this, it occurred to me that the blues heritage of Mississippi and Chicago are now institutionalized in a manner that would have seemed unlikely even 25 years ago. When I visited Maxwell Street, Chicago, in the early 90s, the market was closed and there was no sign that this was one of the crucibles of American music. It is now heritage listed, the market has reopened, and tourism has revived what was a very depressed neighbourhood. Richard Daley’s son, of all people, made this happen! It would be lovely to think that we might one day say that music provided the groundwork for a real change in race relations in America.

As if to make this plain, the first section deals with the ‘myth’ and, specifically, the autobiography Holiday produced in 1957. Lady Sings the Blues was much read at the time but is a book that has always been considered fictitious. He points out that she was forced to suppress the sections that dealt with many of her friendships and romantic relationships. Orson Welles, Charles Laughton, Tallulah Bankhead, Elizabeth Bishop, and several other notables threatened legal action if they were mentioned. Billie’s problems with heroin and her troubles with the law were both well known by the 1950s. No one wanted to be publicly associated with her. The book then became a hodgepodge of stories that emphasized her troubled life. Szwed suggests that the book isn’t fictitious, just incomplete. Like all biographical writing, it reflects the values of the period in which it was written. There is a glut of rock and roll memoirs on the shelves in bookstores at the moment. The selling point is, of course, the opportunity to hear the ‘true’ story from the horse’s mouth. Billie’s autobiography is a reminder that the ‘truth’ is no simple matter.

As if to make this plain, the first section deals with the ‘myth’ and, specifically, the autobiography Holiday produced in 1957. Lady Sings the Blues was much read at the time but is a book that has always been considered fictitious. He points out that she was forced to suppress the sections that dealt with many of her friendships and romantic relationships. Orson Welles, Charles Laughton, Tallulah Bankhead, Elizabeth Bishop, and several other notables threatened legal action if they were mentioned. Billie’s problems with heroin and her troubles with the law were both well known by the 1950s. No one wanted to be publicly associated with her. The book then became a hodgepodge of stories that emphasized her troubled life. Szwed suggests that the book isn’t fictitious, just incomplete. Like all biographical writing, it reflects the values of the period in which it was written. There is a glut of rock and roll memoirs on the shelves in bookstores at the moment. The selling point is, of course, the opportunity to hear the ‘true’ story from the horse’s mouth. Billie’s autobiography is a reminder that the ‘truth’ is no simple matter.