All in the Downs by Shirley Collins, Strange Attractor Press, 2018

All in the Downs by Shirley Collins, Strange Attractor Press, 2018

Jazz ruined her first marriage. Her husband loved it; she didn’t. He played it so much that one night she lost her temper and threw a tea cup against the wall. His love for jazz extended to inviting young jazz musicians to stay with them at their house. Some of these people had drug habits and one day a couple of East End heavies came to the door. Someone owed them money. Shirley Collins wrote them a cheque. Then she wrote a note to her husband. No more jazz; no more jazz musicians. Goodbye.

This was in 1970, by which time Shirley Collins was a famous folk musician in England. She was still mistaken for Judy Collins occasionally by confused interviewers but she had been recording since the 50s and, along with her sister Dolly, made a number of fascinating and well received records. Ten years later, her career was winding down and she had begun a series of jobs as an administrative assistant in various government offices. From the early eighties until she retired in 1995 she worked in offices, typing and filing. In the early 90s, a young co-worker crankily observed that he was stuck working with a bunch of old ladies who had never done anything but work for the government. Shirley said this wasn’t the case. She had been on television, played the Royal Albert Hall and the Sydney Opera House. He apologized. And so he should have!

Why was one of the great figures of the English folk revival typing up council meeting minutes in the 1980s? I imagine Kate Bush coming on the transistor radio in the lunchroom and Shirley looking around to see if anyone noticed how indebted the younger singer was to her. But, sadly, by this stage, Shirley couldn’t sing. She suffered from a condition called dysphonia, otherwise known as ‘marrying someone from Fairport Convention’ syndrome. It started when her second marriage, to former Fairport bassist Ashley Hutchings, disintegrated in the late 70s. The other famous folk sufferer was, yes, Linda Thompson. It’s no joke, of course. The condition, which is still not fully understood, shut down the careers of both these talented performers.

With Ashley Hutchings in the early 70s

She did make an amazing comeback in 2016 at age 81 with the album ‘Lodestar’. Listen to it and then stop moaning about getting old. This is her ‘Blackstar’. All of those fallow years did nothing to dampen her originality and exquisite taste in ancient English songs. Her voice has deepened slightly but, as with her best work of the 60s and 70s, there is a timeless quality to her delivery. There’s no real comparison with any of her near contemporaries. She’s nothing like Sandy Denny or Maddy Pryor or Linda Thompson or anyone else in the folk rock box. On the other hand, she’s not like Peggy Seeger either. I always think of John Clare when I listen to her music. Her England is rural and wild but threatened by enclosure. There are Romany families on the road and a few old Luddites here and there.

The interesting thing about Shirley Collins is that she was always immersed in English folk music without ever succumbing to the almost Stalinist orthodoxy of people like Ewan MacColl. He doesn’t come off very well in the book. An account of a disturbing ‘#Me Too’ moment with him is followed by a hilarious description of him sitting astride a chair at a folk club with eyes closed and a hand to one ear, presumably making sure that the singer on the floor wasn’t performing a song written more than 20 kilometers from where the singer was born. Such were the strict parameters of the English folk politburo of the early 60s. You can imagine what MacColl thought of Donovan!

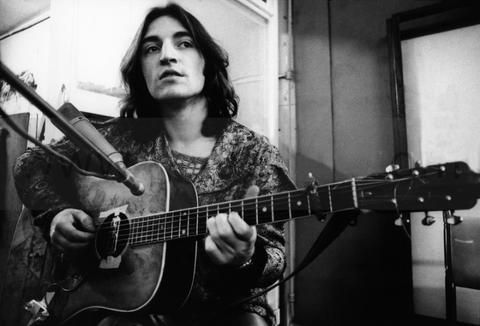

Collins performed traditional material but was always open to innovation. MacColl’s puritanical approach has always struck me as slightly pathological. He wanted to collect, control, and dominate. Shirley Collins simply loved the music. She also realized that it could be preserved without putting it on a shelf in a jar. Her famous 1964 collaboration with Davey Graham, ‘Folk Roots, New Routes’, is a good place to start. Graham, who wrote the instrumental Angi and was a great influence on Jimmy Page, was the definition of far out in the early sixties. He was ostensibly a folk musician but was incorporating outlandish open tunings (he more or less ‘invented’ DADGAD, for instance) and Moroccan rhythms into his sound. Together they recorded English folk songs and, according to many critics, created a key album in the English folk rock story. Some, like Rob Young, the author of Electric Eden, suggest that it is actually the starting point for the genre.

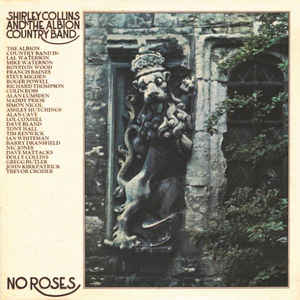

But let’s talk about ‘No Roses’, the greatest album Fairport Convention never made. Except that they sort of did. Most of the ‘Liege and Lief’ era members (only Sandy and Swarbs don’t appear) turn up somewhere on this 1971 album. I’m not going to suggest that it is the equal of that record but if you love ‘Liege and Lief’ and are frustrated by all of the Fairport albums that followed, I might be your new best pal for suggesting this one, if you’ve never heard it. Richard Thompson, Simon Nicol, Ashley Hutchings (it was his group, the Albion Country Band backing her), and Dave Mattacks all appear on the record, along with members of the Young Tradition, Maddy Pryor, sister Dolly, Lal and Mike Waterson, and the awesome Nic Jones. I found out about this record reading Electric Eden and it has become a great favourite.

But let’s talk about ‘No Roses’, the greatest album Fairport Convention never made. Except that they sort of did. Most of the ‘Liege and Lief’ era members (only Sandy and Swarbs don’t appear) turn up somewhere on this 1971 album. I’m not going to suggest that it is the equal of that record but if you love ‘Liege and Lief’ and are frustrated by all of the Fairport albums that followed, I might be your new best pal for suggesting this one, if you’ve never heard it. Richard Thompson, Simon Nicol, Ashley Hutchings (it was his group, the Albion Country Band backing her), and Dave Mattacks all appear on the record, along with members of the Young Tradition, Maddy Pryor, sister Dolly, Lal and Mike Waterson, and the awesome Nic Jones. I found out about this record reading Electric Eden and it has become a great favourite.

Shirley and Dolly 1940

Collins devotes space to both of these records, of course, and to her life among the stars of English folk rock. But the book is far more than a litany of meetings with remarkable guitar players – she did have tea with Jimi Hendrix – or a bitter rant about the music business – something that would be entirely justified in her case. She was born in 1935 and regards her childhood memories of Sussex as the beginning point of her love for English folk culture. I found myself sinking happily into a pre digital world that wasn’t all that different from John Clare’s, in some ways. She weaves a number of folk songs into the narrative. All of them are of interest and there is nothing pedantic in her descriptions. Her knowledge of the tradition is wide. There was a time when men and women roamed England collecting songs from anyone they could find. This was the raw material for the folk revival. Collins describes this process and gives credit to those involved. I was particularly impressed by her admiration for the Romany singers whose contribution is sometimes forgotten and whose descendants remain subject to terrible discrimination.

Where singers like Sandy Denny, Vashti Bunyan and, to a lesser extent, Anne Briggs have become cult figures, Shirley Collins is, to my mind, still wildly under appreciated. She was awarded an MBE and declared a national treasure by Billy Bragg but I feel like she isn’t accorded her rightful street cred. Listen to ‘Anthems in Eden’, a 1969 album with Dolly. You think you’ve heard Freak Folk? This really is folk music and it is freaky stuff, by any measure. You can read all about how it was made in her book. All in the Downs is an endearing and thoughtful memoir for fans and novices alike.

Teasers: Sometimes your heroes are jerks in real life. Shirley isn’t vindictive but there are some devastating portraits in this book. If you’re a fan of Ashley Hutchings…

From Lodestar:

There’s not a lot of old footage of Shirley available but this is from a 1970s BBC documentary:

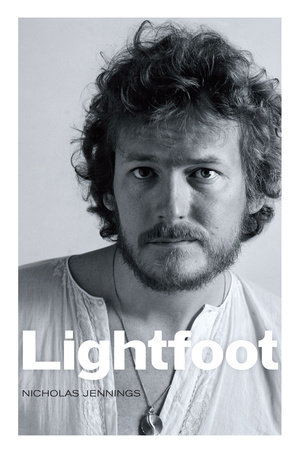

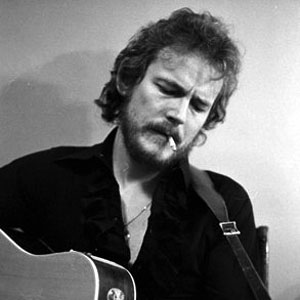

When I was 17, my dad introduced me to his new girlfriend, a woman called Anne. She was in her 40s and was in the habit of punctuating everything she said with one of those smoker’s laughs that sound like a cough. When my dad went into another room to take a phone call, she asked if it was true that I liked music. I said it was. She told me that ‘Gordy’ Lightfoot had written a song about her. Really, I said, which one? Sundown, she told me. Isn’t that about a prostitute? I asked. When my dad returned, Anne said, ‘I think your son just called me a hooker.’ It was awkward.

When I was 17, my dad introduced me to his new girlfriend, a woman called Anne. She was in her 40s and was in the habit of punctuating everything she said with one of those smoker’s laughs that sound like a cough. When my dad went into another room to take a phone call, she asked if it was true that I liked music. I said it was. She told me that ‘Gordy’ Lightfoot had written a song about her. Really, I said, which one? Sundown, she told me. Isn’t that about a prostitute? I asked. When my dad returned, Anne said, ‘I think your son just called me a hooker.’ It was awkward. Where I come from, Gordon Lightfoot is bigger than…well, just about anyone. Put it this way, a lot of Canadians who wouldn’t know a Neil Young song if one backed over them could probably easily name 10 Lightfoot songs. I remember my grandfather throwing Gord’s Gold into the 8 track player and letting it play over and over all day. I can also remember the Canadian bands I loved in the 1980s name checking him in interviews and playing his songs in encores. He played Massey Hall every year to audiences that included Bay Street lawyers, Scarborough tow truck drivers, hippies, punks, Social Studies teachers, and glad handing politicians. He could have run for Parliament, he could have been crowned king.

Where I come from, Gordon Lightfoot is bigger than…well, just about anyone. Put it this way, a lot of Canadians who wouldn’t know a Neil Young song if one backed over them could probably easily name 10 Lightfoot songs. I remember my grandfather throwing Gord’s Gold into the 8 track player and letting it play over and over all day. I can also remember the Canadian bands I loved in the 1980s name checking him in interviews and playing his songs in encores. He played Massey Hall every year to audiences that included Bay Street lawyers, Scarborough tow truck drivers, hippies, punks, Social Studies teachers, and glad handing politicians. He could have run for Parliament, he could have been crowned king.

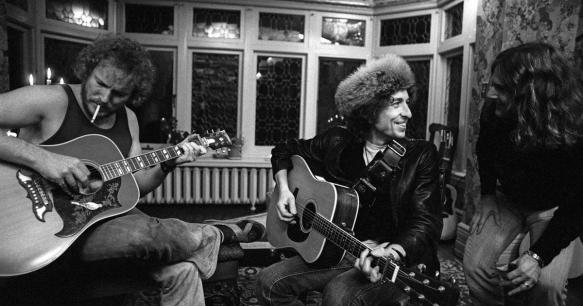

Jennings explores Lightfoot’s relationship with Bob Dylan in some detail. Dylan is a fan, no question. There is a small group of songwriters that Dylan admires. He is generous but fickle on this topic in interviews. Sometimes he mentions John Prine, sometimes it’s Jimmy Buffett (no, really, he said that once) but the name that consistently comes up is Gordon Lightfoot.

Jennings explores Lightfoot’s relationship with Bob Dylan in some detail. Dylan is a fan, no question. There is a small group of songwriters that Dylan admires. He is generous but fickle on this topic in interviews. Sometimes he mentions John Prine, sometimes it’s Jimmy Buffett (no, really, he said that once) but the name that consistently comes up is Gordon Lightfoot.

Pickers and Poets: The Ruthlessly Poetic Singer-Songwriters of Texas by

Pickers and Poets: The Ruthlessly Poetic Singer-Songwriters of Texas by  I was sold when Willis Alan Ramsay turned up in one of the first essays. In the chapters that follow, it becomes clear that many songwriters continue to hold him in very high esteem. He recorded exactly one album in 1972. It sold poorly and disappeared almost immediately. But what a record! You’ll recognise one song on it. Yes, Willis Alan Ramsay wrote Muskrat Love and, what’s more, it’s a great song. His version, that is. He also wrote Angel Eyes, a song that you will either play or wish you had played at your wedding.

I was sold when Willis Alan Ramsay turned up in one of the first essays. In the chapters that follow, it becomes clear that many songwriters continue to hold him in very high esteem. He recorded exactly one album in 1972. It sold poorly and disappeared almost immediately. But what a record! You’ll recognise one song on it. Yes, Willis Alan Ramsay wrote Muskrat Love and, what’s more, it’s a great song. His version, that is. He also wrote Angel Eyes, a song that you will either play or wish you had played at your wedding.

The introduction includes a cringe-worthy explanation of why so few women are included but the chapter devoted exclusively to them is perhaps the best in the book. There are also chapters on newish singer songwriters like Kacey Musgraves and Terri Hendrix in the last section of the book. The whole thing, at times, seems edited by committee so perhaps they forgot. The chapter on Don Henley (yes, from Texas, shame about his anaemic music) was mercifully brief but still too long for this reader. The sections on figures like Steve Earle and Lucinda Williams contained far too much general information that is already widely available. The chapter on Rodney Crowell, on the other hand, was fascinating. Guy Clark seemed underplayed throughout the book though the essay by Tamara Saviano bodes well for her recent biography of the man. But these are just quibbles about an engaging and informative book. Any book on music that I have to put down so that I can listen to an artist or album that I don’t know gets high marks from me. It took me weeks to get through this one! Discovering David Rodriguez alone was worth the cover price.

The introduction includes a cringe-worthy explanation of why so few women are included but the chapter devoted exclusively to them is perhaps the best in the book. There are also chapters on newish singer songwriters like Kacey Musgraves and Terri Hendrix in the last section of the book. The whole thing, at times, seems edited by committee so perhaps they forgot. The chapter on Don Henley (yes, from Texas, shame about his anaemic music) was mercifully brief but still too long for this reader. The sections on figures like Steve Earle and Lucinda Williams contained far too much general information that is already widely available. The chapter on Rodney Crowell, on the other hand, was fascinating. Guy Clark seemed underplayed throughout the book though the essay by Tamara Saviano bodes well for her recent biography of the man. But these are just quibbles about an engaging and informative book. Any book on music that I have to put down so that I can listen to an artist or album that I don’t know gets high marks from me. It took me weeks to get through this one! Discovering David Rodriguez alone was worth the cover price.

Homeward Bound: The Life of Paul Simon by Peter Ames Carlin, Henry Holt, 2016

Homeward Bound: The Life of Paul Simon by Peter Ames Carlin, Henry Holt, 2016

It didn’t last long. Around 1970, Art’s involvement in the Catch 22 film proved too much for Simon’s fragile ego. He went solo, sank into depression when his first album only sold 2 million copies, and finally phoned up Artie to appear with him on the second ever episode of Saturday Night Live. “So, you came crawling back?” he said. The reunion lasted for one glorious song, My Little Town.

It didn’t last long. Around 1970, Art’s involvement in the Catch 22 film proved too much for Simon’s fragile ego. He went solo, sank into depression when his first album only sold 2 million copies, and finally phoned up Artie to appear with him on the second ever episode of Saturday Night Live. “So, you came crawling back?” he said. The reunion lasted for one glorious song, My Little Town.

And that brings us to Graceland. This is where the book really takes flight. What a story! Graceland was an album that I loathed with an almost exquisite fervour when it appeared in 1986. It sounded like BMW coke music, the kind of thing Gordon Gecko would have in his car. Man, the 80s were awful. Don’t let anyone tell you differently, kids. Simon predictably ran into trouble when he went to South Africa and recorded with a group of mbaqanga musicians that he first heard on a cassette that he forgot to give back to Heidi Berg. Before he even got around to his usual shenanigans with writing credits, he was in trouble with the ANC and found himself on a UN blacklist of musicians who had broken the embargo against working in South Africa.

And that brings us to Graceland. This is where the book really takes flight. What a story! Graceland was an album that I loathed with an almost exquisite fervour when it appeared in 1986. It sounded like BMW coke music, the kind of thing Gordon Gecko would have in his car. Man, the 80s were awful. Don’t let anyone tell you differently, kids. Simon predictably ran into trouble when he went to South Africa and recorded with a group of mbaqanga musicians that he first heard on a cassette that he forgot to give back to Heidi Berg. Before he even got around to his usual shenanigans with writing credits, he was in trouble with the ANC and found himself on a UN blacklist of musicians who had broken the embargo against working in South Africa.

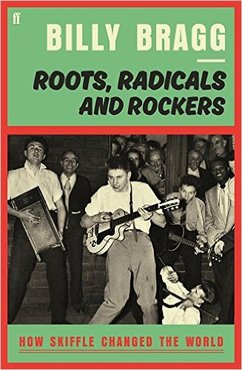

Roots, Radicals and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World by Billy Bragg, Faber & Faber, 2017

Roots, Radicals and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World by Billy Bragg, Faber & Faber, 2017

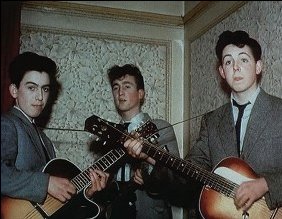

If you’ve never listened to skiffle, Billy presents the genre in great detail, picking out the notable from the forgettable. Ever wondered about the song ‘Maggie Mae’ on The Beatles Let It Be album? The original was the biggest hit of a Liverpool outfit called The Vipers. One of the issues for skiffle bands in the studio was the tendency for older producers to top up their sound with strings and other embellishments. The Vipers, fortunately, found a young producer who correctly noted that their rawness was part of their appeal. He simply recorded them, live on the floor. That young producer would use a similar strategy with another band from Liverpool a couple of years later. His name was George Martin.

If you’ve never listened to skiffle, Billy presents the genre in great detail, picking out the notable from the forgettable. Ever wondered about the song ‘Maggie Mae’ on The Beatles Let It Be album? The original was the biggest hit of a Liverpool outfit called The Vipers. One of the issues for skiffle bands in the studio was the tendency for older producers to top up their sound with strings and other embellishments. The Vipers, fortunately, found a young producer who correctly noted that their rawness was part of their appeal. He simply recorded them, live on the floor. That young producer would use a similar strategy with another band from Liverpool a couple of years later. His name was George Martin.

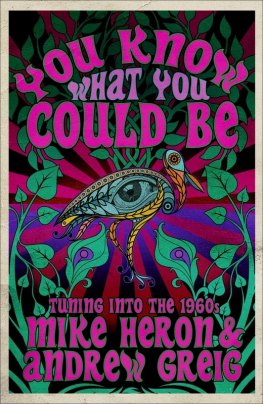

You Know What You Could Be: Tuning Into the 60s by Mike Heron and Andrew Greig, riverrun 2017

You Know What You Could Be: Tuning Into the 60s by Mike Heron and Andrew Greig, riverrun 2017

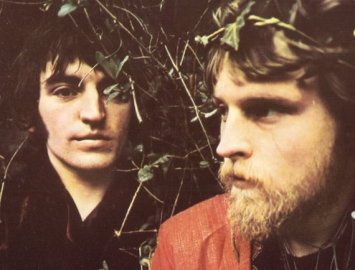

There are a number of books on The Incredible String Band that will provide a chronological account of their musical journey. Rob Young’s take on their career in Electric Eden is particularly good. But You Know What You Could Be is something different. Surely a band’s story must include their audience to some extent. Without going all ‘trees falling in the forest’ here, the effect of the music is often as significant as the music itself. Most rock and roll biographies will trace the influence of their subject on subsequent acts but what about the ordinary fans whose lives are changed, sometimes dramatically, by the music? Clearly, no one wants to read a whole book of Led Zeppelin fans cooing about Knebworth or, worse, a Deadhead memoir (there are many, if you do!) but I like what Greig has done in this book.

There are a number of books on The Incredible String Band that will provide a chronological account of their musical journey. Rob Young’s take on their career in Electric Eden is particularly good. But You Know What You Could Be is something different. Surely a band’s story must include their audience to some extent. Without going all ‘trees falling in the forest’ here, the effect of the music is often as significant as the music itself. Most rock and roll biographies will trace the influence of their subject on subsequent acts but what about the ordinary fans whose lives are changed, sometimes dramatically, by the music? Clearly, no one wants to read a whole book of Led Zeppelin fans cooing about Knebworth or, worse, a Deadhead memoir (there are many, if you do!) but I like what Greig has done in this book.

These Are The Days: Stories and Songs by Mick Thomas, Melbourne Books, 2017

These Are The Days: Stories and Songs by Mick Thomas, Melbourne Books, 2017

I was particularly struck by the chapter on Sisters of Mercy. This song from Weddings Parties Anything’s Roaring Days album was written in response to a nurses’ strike in the 1980s. In 2012 he was invited to play it for a large group of nurses at a strike meeting in the Melbourne Convention Centre. This chapter might have been a straightforward story about the song and how things never change. But it wasn’t. Instead, Thomas talks about a critique he’d copped in another setting for overdoing the emotional dimension of a song about asbestos poisoning. He was accused of emphasising the victimhood of the sufferers instead of celebrating their fighting spirit. The charge seemed terribly unfair and few singers would have the courage to revisit such a hardline dressing down. Mick then finds himself playing Sisters of Mercy for the striking nurses and choking back tears so as to avoid a repeat of the asbestos song episode. He manages it but only just. My own eyes grew a bit misty reading this chapter. The idea of a singer at a strike meeting in these cynical times is itself moving!

I was particularly struck by the chapter on Sisters of Mercy. This song from Weddings Parties Anything’s Roaring Days album was written in response to a nurses’ strike in the 1980s. In 2012 he was invited to play it for a large group of nurses at a strike meeting in the Melbourne Convention Centre. This chapter might have been a straightforward story about the song and how things never change. But it wasn’t. Instead, Thomas talks about a critique he’d copped in another setting for overdoing the emotional dimension of a song about asbestos poisoning. He was accused of emphasising the victimhood of the sufferers instead of celebrating their fighting spirit. The charge seemed terribly unfair and few singers would have the courage to revisit such a hardline dressing down. Mick then finds himself playing Sisters of Mercy for the striking nurses and choking back tears so as to avoid a repeat of the asbestos song episode. He manages it but only just. My own eyes grew a bit misty reading this chapter. The idea of a singer at a strike meeting in these cynical times is itself moving!