When I was 17, my dad introduced me to his new girlfriend, a woman called Anne. She was in her 40s and was in the habit of punctuating everything she said with one of those smoker’s laughs that sound like a cough. When my dad went into another room to take a phone call, she asked if it was true that I liked music. I said it was. She told me that ‘Gordy’ Lightfoot had written a song about her. Really, I said, which one? Sundown, she told me. Isn’t that about a prostitute? I asked. When my dad returned, Anne said, ‘I think your son just called me a hooker.’ It was awkward.

When I was 17, my dad introduced me to his new girlfriend, a woman called Anne. She was in her 40s and was in the habit of punctuating everything she said with one of those smoker’s laughs that sound like a cough. When my dad went into another room to take a phone call, she asked if it was true that I liked music. I said it was. She told me that ‘Gordy’ Lightfoot had written a song about her. Really, I said, which one? Sundown, she told me. Isn’t that about a prostitute? I asked. When my dad returned, Anne said, ‘I think your son just called me a hooker.’ It was awkward.

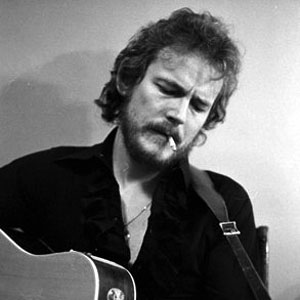

Sundown is a heavy song. It was always on the radio when I was growing up in Canada in the 1970s but I never took much notice of it. When I began to listen to Lightfoot more seriously as an adult, I was struck by its darkness. The singer pictures this woman in various outfits and is filled by jealously and self loathing. In the end, alcohol is his only refuge. There is something oddly vulnerable about it. The singer seems powerless and doomed. Even his veiled threats – you better take care – sound hollow.

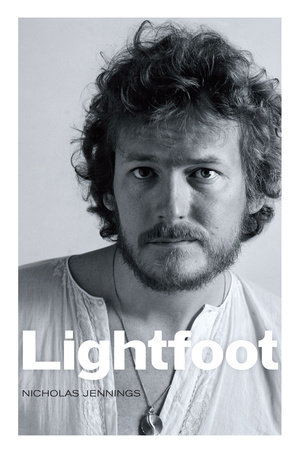

And it turns out that the song was not an ode to my dad’s girlfriend. In Nicholas Jenning’s new biography, Lightfoot, we learn that the song is almost certainly about Cathy Evelyn Smith. Sound familiar? Yes, the same woman who went to jail for her involvement in John Belushi’s death at the Chateau Marmont. If you have read Robbie Robertson’s memoir, you may remember her in connection to Levon Helm but that really is another story.

Where I come from, Gordon Lightfoot is bigger than…well, just about anyone. Put it this way, a lot of Canadians who wouldn’t know a Neil Young song if one backed over them could probably easily name 10 Lightfoot songs. I remember my grandfather throwing Gord’s Gold into the 8 track player and letting it play over and over all day. I can also remember the Canadian bands I loved in the 1980s name checking him in interviews and playing his songs in encores. He played Massey Hall every year to audiences that included Bay Street lawyers, Scarborough tow truck drivers, hippies, punks, Social Studies teachers, and glad handing politicians. He could have run for Parliament, he could have been crowned king.

Where I come from, Gordon Lightfoot is bigger than…well, just about anyone. Put it this way, a lot of Canadians who wouldn’t know a Neil Young song if one backed over them could probably easily name 10 Lightfoot songs. I remember my grandfather throwing Gord’s Gold into the 8 track player and letting it play over and over all day. I can also remember the Canadian bands I loved in the 1980s name checking him in interviews and playing his songs in encores. He played Massey Hall every year to audiences that included Bay Street lawyers, Scarborough tow truck drivers, hippies, punks, Social Studies teachers, and glad handing politicians. He could have run for Parliament, he could have been crowned king.

However, the living legend status is something of a consolation prize for a singer whose viability as a recording artist came to crashing halt in about 1980. He kept making records but people stopped buying them. I own everything he released up to and including Endless Wire, which appeared in 1978. I had never even heard of the follow up, Dream Street Rose or any of the subsequent records before reading this book. I suppose there are superfans that would snort at my amateurishness here but the sales figures tell the same story. Thanks for all the great songs, Gord. Here’s your gold watch. The man was 42!

Lightfoot is a solid, chronological account of Gord’s life and work. It is a respectful and workmanlike book – rather Canadian, really! There are no startling revelations or particularly original insights. Instead, Jennings strives to build the character of the man through a number of significant episodes. Lightfoot is a very private fellow with a certain reputation for difficult behaviour. He has been married many times and has had troubles with alcohol. Jennings draws a picture of a hard working and shy man who couldn’t have been less temperamentally suited to stardom. He grew up in Orillia Ontario, a town probably not so different to Hibbing Minnesota. Unlike Hibbing’s favourite son however, Gord was never headed for Malibu via New York. I was interested to learn that throughout his long career he has always lived in Toronto. He spent years living on Alexander St, behind Maple Leaf Gardens, before moving to Rosedale. These days, he lives on Bridle Path, a glamorous address by Toronto standards but hardly Malibu.

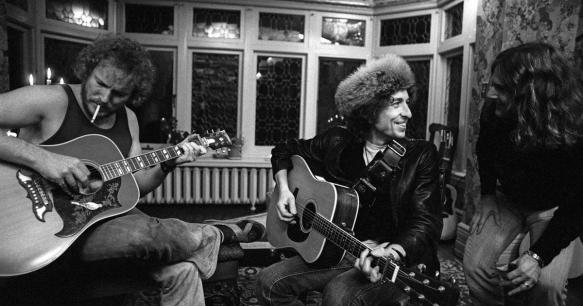

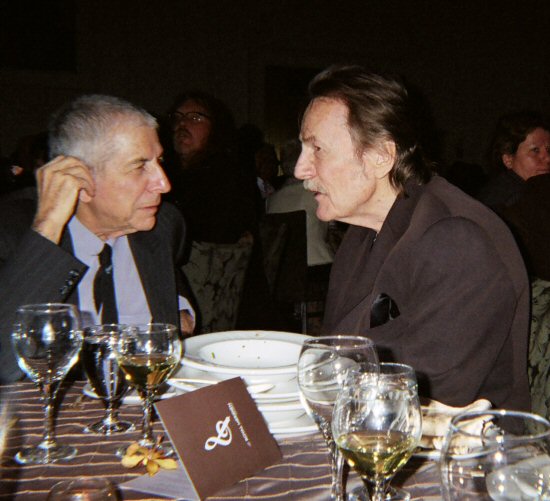

Jennings explores Lightfoot’s relationship with Bob Dylan in some detail. Dylan is a fan, no question. There is a small group of songwriters that Dylan admires. He is generous but fickle on this topic in interviews. Sometimes he mentions John Prine, sometimes it’s Jimmy Buffett (no, really, he said that once) but the name that consistently comes up is Gordon Lightfoot.

Jennings explores Lightfoot’s relationship with Bob Dylan in some detail. Dylan is a fan, no question. There is a small group of songwriters that Dylan admires. He is generous but fickle on this topic in interviews. Sometimes he mentions John Prine, sometimes it’s Jimmy Buffett (no, really, he said that once) but the name that consistently comes up is Gordon Lightfoot.

Lightfoot has taken a different path from Bob in many respects. He was never the voice of a generation or a rock god. He never partied at the Factory or fell to pieces in the back of a Rolls with John Lennon. Gordon Lightfoot’s career has been comparatively low key. In the flashy dramatic world of popular music, there has always been something subtle about him. His albums, particularly the early ones, are quiet affairs. A small band, some strings here and there, and minimal overdubbing. I used to wish that Bob Johnston had produced at least one record for Lightfoot in the sixties. Are we rolling, Gord? But, maybe I’m happy that he didn’t. His 1970 Sit Down Stranger album, quickly renamed If I Could Read Your Mind after its most famous song, is a case in point. To me, this album is what Self Portrait should have been and is perhaps a glimpse of what Dylan had in mind. It was recorded in LA but there is a distinctly Nashville sensibility to it. It’s easy to see why Kris Kristofferson and Johnny Cash were such fans. The songs are beautifully written and unobtrusively performed. From MOR to Outlaw Country to the Laurel Canyon songsmiths, this was a masterclass in showcasing your work.

But back to Dylan. Bob doesn’t always work well with others and his relationship with Gord had always been cordial, if guarded. When the Rolling Thunder Tour pulled into Toronto in early December of 1975, Gord was asked to play the second last set in the program. He played The Watchman’s Gone and Sundown. Try to imagine following that on a Toronto stage. Bob Dylan might have been the only person on earth in those days with a chance but I’m willing to bet that his set was something of anti climax. Anyone who was there is welcome to correct me!

After the show, everybody, and I mean everybody, went back to Gord’s place in Rosedale. The party was legendary. Mick Ronson was there, trading stories with Ronnie Hawkins. Joni Mitchell and Joan Baez were avoiding each other while all eyes were on Scarlet Rivera. Then that lovable scamp Bobby Neuwirth threw his leather jacket into the fireplace and filled the whole house with black smoke. What a fun guy. See if he’s available for your next soiree.

Meanwhile, Bob and Gord had retreated to the parlor to jam. The wildest rock and roll party in Toronto history was unfolding downstairs but Dylan and Lightfoot were quietly exchanging songs. Oh, to have a decent recording. Alas, there is only a fragment of Lightfoot singing Ballad in Plain D, of all songs. Lightfoot is a remarkable man but the fact that he knew the words to Ballad in Plain D might just make him some kind of superhero. In any case, as Jennings points out, neither man was there to party. This was a summit meeting. Everyone has seen Bob’s exchange with Donovan in Don’t Look Back. This was not like that.

“Hey Roger, he knows Ballad in Plain D!”

I suppose Jennings uses this episode to highlight the depth of Gordon Lightfoot’s commitment to songwriting. Sometimes, while reading, I had the sense of a man who might have preferred playing to a crowd of receptive regulars at his neighborhood pub to touring the world as a superstar. In one telling episode that took place in the 1970s, Gord signed on with a famous agent who managed a number of mainstream stars at the time. He wanted to take the singer to the next level where he would be on television, headlining regularly in Vegas, and selling zillions of records on the back of duets with divas, etc. After a few days, Lightfoot got cold feet and asked him to tear up the contract. He didn’t want to be Kenny Rogers or Tom Jones. Instead, he started taking the Toronto subway to the gym because he felt bad about the environment.

Nicholas Jennings had some access to the occasionally prickly singer while he was writing the book. It’s hard to imagine that such a modest and private man will ever write a memoir so this might be as close as we get. If you are a fan, don’t forget to read Dave Bidini’s utterly brilliant Writing Gordon Lightfoot too. There you go, you can ask for both for Christmas and spend Boxing Day on the couch reading while everyone else watches college football.

Meanwhile, Gordon Lightfoot will no doubt be playing his annual gig at Massey Hall and releasing a new album this year. Last week he was in Peterborough donating his canoe to the Canoe Museum there. A Canadian legend? You bet.

Teasers: The whole story behind If I Could Read Your Mind; his early days as a singing sensation in Orillia, Ontario.

Trouble In Mind: Bob Dylan’s Gospel Period – What Really Happened by Clinton Heylin, 2017

Trouble In Mind: Bob Dylan’s Gospel Period – What Really Happened by Clinton Heylin, 2017

The first, Slow Train Coming, is surely one of Bob Dylan’s finest moments. After a dry spell in the early 70s, Bob began to write from a more personal place. His ability with imagery remained but he left behind the Beat babble for lyrics that seemed to come from a deeper source. The older I get, the more difficult I find it to listen to the raw pain on 1975’s Blood on the Tracks. Street Legal (1978) is, for me, on par with Neil Young’s Time Fades Away. It sounds like a ragged cry of bewilderment. Slow Train thus sounds like an answer, of sorts. The songs are beautifully constructed and feature little of the obfuscation that Dylan was so well known for at the time.

The first, Slow Train Coming, is surely one of Bob Dylan’s finest moments. After a dry spell in the early 70s, Bob began to write from a more personal place. His ability with imagery remained but he left behind the Beat babble for lyrics that seemed to come from a deeper source. The older I get, the more difficult I find it to listen to the raw pain on 1975’s Blood on the Tracks. Street Legal (1978) is, for me, on par with Neil Young’s Time Fades Away. It sounds like a ragged cry of bewilderment. Slow Train thus sounds like an answer, of sorts. The songs are beautifully constructed and feature little of the obfuscation that Dylan was so well known for at the time. It took me years to finally sit down and listen to the second album in the series, Saved. The original cover art was confronting and the stridency of the Christian messages stung critics who felt as though they’d allowed him a free pass on one religious record already. The negative reviews in retrospect seem to be all about discomfort with the lyrics and the context of the album, rather than the music. I wonder how many people, like me, went running home to listen to it after hearing John Doe’s version of Pressing On in Todd Haynes’ film, I’m Not There. I suspect many found a far better album than they expected. I sure did!

It took me years to finally sit down and listen to the second album in the series, Saved. The original cover art was confronting and the stridency of the Christian messages stung critics who felt as though they’d allowed him a free pass on one religious record already. The negative reviews in retrospect seem to be all about discomfort with the lyrics and the context of the album, rather than the music. I wonder how many people, like me, went running home to listen to it after hearing John Doe’s version of Pressing On in Todd Haynes’ film, I’m Not There. I suspect many found a far better album than they expected. I sure did!

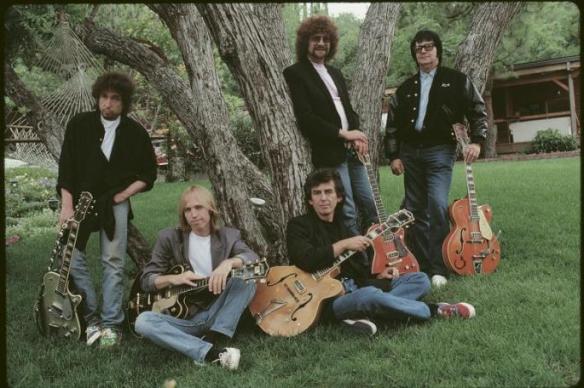

The Traveling Wilburys: The Biography by Nick Thomas, Guardian Express Media (E-Book) 2017

The Traveling Wilburys: The Biography by Nick Thomas, Guardian Express Media (E-Book) 2017 About 8 months later, a 13 year old boy called Tom Petty in Gainesville Florida was watching The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show, completely unaware that he would one day form a band with the shy fellow playing a Gretsch Country Gentleman. Four or five months after that, in the summer of 1964, George and his band mates were supposedly introduced to marijuana (Rock and Roll myth #540: They didn’t come across weed in Hamburg? Yeah right!) by a chatty fellow from Minnesota named Bob Dylan. As they puffed away in the Delmonico Hotel, Bob probably didn’t foresee the day when he would accept an invitation to join George Harrison’s band.

About 8 months later, a 13 year old boy called Tom Petty in Gainesville Florida was watching The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show, completely unaware that he would one day form a band with the shy fellow playing a Gretsch Country Gentleman. Four or five months after that, in the summer of 1964, George and his band mates were supposedly introduced to marijuana (Rock and Roll myth #540: They didn’t come across weed in Hamburg? Yeah right!) by a chatty fellow from Minnesota named Bob Dylan. As they puffed away in the Delmonico Hotel, Bob probably didn’t foresee the day when he would accept an invitation to join George Harrison’s band.

Thomas’s book makes no special claims for the songs on the album. They were written quickly by a group of very experienced songwriters throwing out lines to each other. Lyrically speaking, nothing on either record is a patch on any of the members’ own work, your feelings about ELO notwithstanding. But this record is all about atmosphere and sound. George Harrison’s lovely guitar work; Roy’s otherworldly voice; Dylan’s strangeness; and Petty’s punk rock sneer all combine here for something very special. Jeff Lynne adds his acoustic wall of sound and old school rockabilly sensibility for the icing on an estimable cake.

Thomas’s book makes no special claims for the songs on the album. They were written quickly by a group of very experienced songwriters throwing out lines to each other. Lyrically speaking, nothing on either record is a patch on any of the members’ own work, your feelings about ELO notwithstanding. But this record is all about atmosphere and sound. George Harrison’s lovely guitar work; Roy’s otherworldly voice; Dylan’s strangeness; and Petty’s punk rock sneer all combine here for something very special. Jeff Lynne adds his acoustic wall of sound and old school rockabilly sensibility for the icing on an estimable cake. For Tom Petty, October 20, 1950 – October 2, 2017

For Tom Petty, October 20, 1950 – October 2, 2017

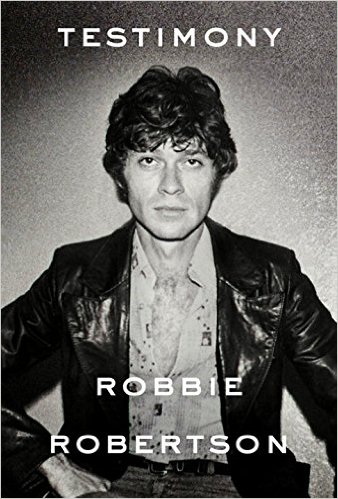

Testimony by Robbie Robertson, Deckle Edge 2016

Testimony by Robbie Robertson, Deckle Edge 2016

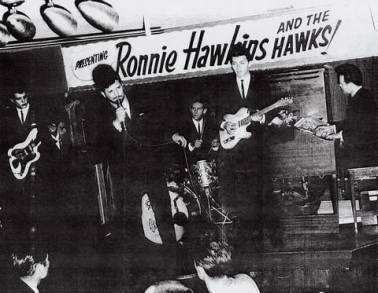

Robertson is particularly good on his early days with Ronnie Hawkins and the evolution of The Hawks. His growing friendship with Levon is at the heart of these sections but he also brings Hawkins, the sort of Dumbledore figure in The Band’s story, to life in all his manic glory. Slowly, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, and the arch eccentric, Garth Hudson of London Ontario, make their way into the Hawks. The band conquers Yonge St and all its young women. They play dives at Wasaga Beach, they play dives on the Mississippi. Robertson was 16 when he joined up. When The Band’s first album appeared in 1968, they had been on the road since the late 50s. The Beatles’ Hamburg period is, at least according to Malcolm Gladwell, an important factor in everything that followed. There is a special ingredient in The Band’s music that is sometimes hard to identify. Robbie’s wonderful evocation of the band’s early years provides an important clue, I believe. The threads of rockabilly, rhythm and blues, pop, blues, and a country ballad or two are all part of the fabric of The Band’s sound.

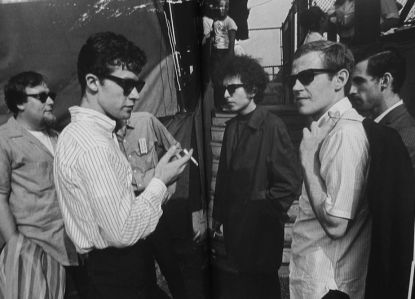

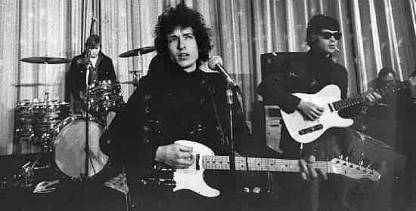

Robertson is particularly good on his early days with Ronnie Hawkins and the evolution of The Hawks. His growing friendship with Levon is at the heart of these sections but he also brings Hawkins, the sort of Dumbledore figure in The Band’s story, to life in all his manic glory. Slowly, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, and the arch eccentric, Garth Hudson of London Ontario, make their way into the Hawks. The band conquers Yonge St and all its young women. They play dives at Wasaga Beach, they play dives on the Mississippi. Robertson was 16 when he joined up. When The Band’s first album appeared in 1968, they had been on the road since the late 50s. The Beatles’ Hamburg period is, at least according to Malcolm Gladwell, an important factor in everything that followed. There is a special ingredient in The Band’s music that is sometimes hard to identify. Robbie’s wonderful evocation of the band’s early years provides an important clue, I believe. The threads of rockabilly, rhythm and blues, pop, blues, and a country ballad or two are all part of the fabric of The Band’s sound. Speaking of the Nobel Laureate, Robbie is very good on the 1966 tour. There has been so much written about it that I wondered if he would bother spending too much time there. He does and manages to provide a unique perspective. Dylan is one of a long series of ‘father figures’ in Robertson’s life. He never actually says this but Ronnie Hawkins gives way to Levon who gives way to Dylan who gives way to Albert Grossman who gives way to David Geffen who gives way to Martin Scorcese. Dylan’s intelligence and absolute cool headedness in every situation impresses the young guitarist as he ducks flying objects night after night on the ‘Judas’ tour.

Speaking of the Nobel Laureate, Robbie is very good on the 1966 tour. There has been so much written about it that I wondered if he would bother spending too much time there. He does and manages to provide a unique perspective. Dylan is one of a long series of ‘father figures’ in Robertson’s life. He never actually says this but Ronnie Hawkins gives way to Levon who gives way to Dylan who gives way to Albert Grossman who gives way to David Geffen who gives way to Martin Scorcese. Dylan’s intelligence and absolute cool headedness in every situation impresses the young guitarist as he ducks flying objects night after night on the ‘Judas’ tour. Following the section on the first album, the tone of Testimony shifts in a subtle way. Rick Danko manages to break his neck in a car accident before their first tour and Richard Manuel’s drinking starts to make an impact. Then Levon Helm discovers heroin. Robbie Robertson is a gentleman. He doesn’t scold or preach but the sense of a lost opportunity is discernible in the folds of his prose. I doubt that anyone will ever top this band’s first two albums but I think Robbie feels as though the records that followed could have been a lot better. He doesn’t think much of Cahoots, for instance. While it isn’t perhaps on par with its three predecessors, an album with Life is a Carnival, When I Paint My Masterpiece, and The River Hymn still must rank as one of the ten best albums of the 1970s.

Following the section on the first album, the tone of Testimony shifts in a subtle way. Rick Danko manages to break his neck in a car accident before their first tour and Richard Manuel’s drinking starts to make an impact. Then Levon Helm discovers heroin. Robbie Robertson is a gentleman. He doesn’t scold or preach but the sense of a lost opportunity is discernible in the folds of his prose. I doubt that anyone will ever top this band’s first two albums but I think Robbie feels as though the records that followed could have been a lot better. He doesn’t think much of Cahoots, for instance. While it isn’t perhaps on par with its three predecessors, an album with Life is a Carnival, When I Paint My Masterpiece, and The River Hymn still must rank as one of the ten best albums of the 1970s. This is something different, an unusual rock and roll memoir where the paucity of information functions as a kind of subtext. Robbie hasn’t come to terms with The Band and has perhaps been stung by his ‘Yoko-isation’ by fans and critics. I enjoyed Testimony enormously but this is perhaps a more melancholy book than the author intended.

This is something different, an unusual rock and roll memoir where the paucity of information functions as a kind of subtext. Robbie hasn’t come to terms with The Band and has perhaps been stung by his ‘Yoko-isation’ by fans and critics. I enjoyed Testimony enormously but this is perhaps a more melancholy book than the author intended. Small Town Talk by Barney Hoskyns, Da Capo Press 2016

Small Town Talk by Barney Hoskyns, Da Capo Press 2016

He thought that she was something truly special. And he was right! Anyone else noticed that Janis seems to be out of fashion at the moment? What’s that about?

He thought that she was something truly special. And he was right! Anyone else noticed that Janis seems to be out of fashion at the moment? What’s that about?