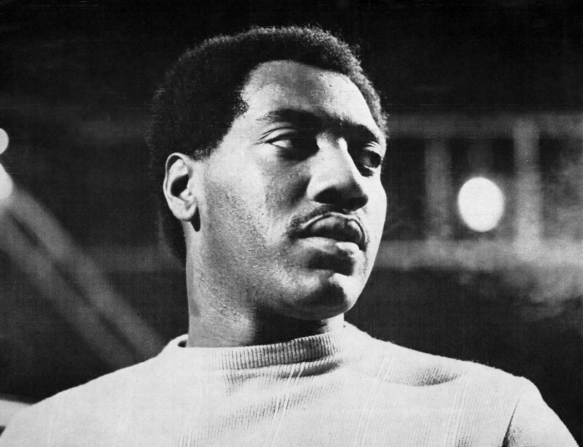

Otis Redding: An Unfinished Life by Jonathan Gould, Crown 2017

Otis Redding: An Unfinished Life by Jonathan Gould, Crown 2017

Is it possible that Otis Redding’s performance at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival is one of the great moments in the history of western culture? Fifty years ago, in the wee hours of a Sunday morning, long after Hugh Masekela’s endless set put everything behind schedule, a 25 year old from Macon, Georgia came onstage and blew everyone who had played before, and just about everyone who was yet to play, off the stage. Jimi Hendrix felt it necessary to light his guitar on fire. Bob Weir reckoned he’d seen God. Such was the Otis effect.

Bob Weir isn’t far from wrong. Otis’s performance, fortunately captured on film, is transcendent. It’s the best Springsteen show you’ve ever seen mixed up with a sort of soul review version of King Lear. It’s what every band tries to do onstage. It’s emotional but seamless. It’s ragged but never sloppy. Otis makes a personal connection with the audience, row by row, seat by seat. There is a clip of him singing ‘I’ve Been Loving You Too Long’ at the end of the review. Make sure you are sitting down.

“I liked that guitar, Otis!”

California was good to Otis. A few months later he wrote Dock of the Bay on a houseboat in Sausalito. He should have stayed. Instead, he went back to his punishing touring schedule and died in a plane crash on December 10th of that same year. All that energy, all that extraordinary talent that was on show at Monterey, disappeared in an instant.

Jonathan Gould’s new biography, Otis Redding: An Unfinished Life begins with his appearance at the festival, backtracks to his early life, and finishes with the slow demise of Stax Records in the 1970s. It’s an appropriate ending. Many, including guitarist Steve Cropper, have stated that Stax was never the same after Otis died. This is by no means the first book to link the Memphis record label’s decline back to his death. Otis was instrumental to its rise and embodied its spirit. Gould acknowledges this but suggests that Otis’ story is much more far reaching than the rise and fall of a record label.

Consider this: Otis Redding was born in 1941, making him an almost exact contemporary of John Lennon and Paul McCartney. But if The Beatles sprang from a Victorian industrial port city, Otis was born into another 19th century altogether. Georgia, in 1941, remained segregated at all levels of society. Many of the most severe Jim Crow laws were still in effect. Those that weren’t, were still there in spirit. The civil rights movement wasn’t even on the horizon. Just over 25 years later, at the end of his short life, Otis was living in a very different America. His life spanned a period of significant change. In fact, by 1967, the era-defining civil rights movement was giving way to Black Power and more militant figures were replacing the soon to be assassinated Dr King. There is a moment late in the book where Otis is being interviewed by Life Magazine and is interrupted by Rap Brown, a figure that would have been unimaginable ten years earlier, let alone at the time of Otis’ birth. That said, when Otis decided to buy a farm outside of Macon in the mid sixties, he still had to make sure that the mainly white residents of the community would be comfortable with his presence. He told his manager that he didn’t want a cross burning on his lawn.

Gould weaves Redding’s story into the broader narrative of African American life in the mid 20th century. His generation of singers, including his occasional rival James Brown, followed the examples of Ray Charles and Sam Cooke who had both worked hard to maintain control over their careers. The young Otis had to prove himself several times in new neighborhoods when the family moved for work in the 1950s. The man that emerges in this book is no pushover and this is not the story of how a black entertainer was ripped off by unscrupulous white men. From the beginning, Otis chose the people around him carefully and, for the most part, avoided the usual pitfalls musicians encounter when their music begins to make money.

Gould weaves Redding’s story into the broader narrative of African American life in the mid 20th century. His generation of singers, including his occasional rival James Brown, followed the examples of Ray Charles and Sam Cooke who had both worked hard to maintain control over their careers. The young Otis had to prove himself several times in new neighborhoods when the family moved for work in the 1950s. The man that emerges in this book is no pushover and this is not the story of how a black entertainer was ripped off by unscrupulous white men. From the beginning, Otis chose the people around him carefully and, for the most part, avoided the usual pitfalls musicians encounter when their music begins to make money.

But this was still America in the sixties and Otis was consigned to the R&B market and long tours on the ‘Chitlin Circuit’. In his lifetime, he was far more popular in Europe than in America. The Rolling Stones were early fans and John Lennon named him as his favourite singer in a mid sixties interview. His first number one single in America was ‘(Sittin’ on the) Dock of the Bay’ which reached that position on March 16 1968, almost 4 months after he died.

Gould is very good on the nuts and bolts of Otis’s various business relationships. Almost in the manner of Franco Moretti’s exacting work on the history of the novel, Gould uses detailed examples from contracts and booking arrangements to illuminate the precise nature of these relationships. This in turn puts some meat on the bones of the social context of the story. Redding’s association with his white manager, Phil Walden, is examined closely and functions as something of a metaphor for the changes that were taking place in the wider society. It is well known that Jimi Hendrix came under increasing pressure from African American activists to avoid using white backing musicians and managers. It’s an open question as to whether Otis would have been subjected to similar pressure. He had already shown a distinct lack of interest in politics – but then so did Hendrix.

Steve Cropper, Genius

From my perspective, Gould is better on social history than music. When I read a music biography, I want to finish with a deeper sense of the subject’s body of work. This, I’m afraid, did not happen. His background material on minstrel groups, the blackface phenomenon, and southern gospel is concisely delivered and appropriate to his narrative but it’s all familiar material. I was surprised initially at his dismissal of an early recording by Redding called ‘Shout Bamalama’. Yes, it’s a blatant Little Richard rip off but it is still a glorious piece of music. Gould treats it like embarrassing juvenalia. I wonder if he realizes that it has been covered by Eddie Hinton, Jim Dickinson, and The Detroit Cobras. They liked it!

Astonishingly, he seems unhappy with Otis’s body of work at Stax Records. His underlying point appears to be that Stax was essentially an amateur operation run by a hayseed – Jim Stewart. Over and over, Gould points to instances where he believes Redding’s career was mishandled. Most surprising is his unstated but obvious contention that Otis would have been better off with Jerry Wexler at Atlantic like Wilson Pickett. Pickett recorded at various studios including Fame in Muscle Shoals but his sound was created at Stax. The Fame recordings are magic, of course, but they were an attempt to recreate the Stax sound. I can see the point he is making from a management perspective but I seriously dispute that the vast amount of Otis Redding’s output would have sounded better with the Swampers at Fame or Chips Moman’s crew at American Studios. Different perhaps, but better? Better than ‘Cigarettes and Coffee’ from The Soul Album? Listen to the beginning with Packy Axton’s sax and Wayne Jackson’s trumpet on top of Al Jackson’s drums. Then there is a perfectly timed restrained guitar lick from Steve Cropper just before Otis starts to sing. In 12 seconds, the 3am atmosphere of the song is established. Could Jerry Wexler do better? I doubt he would have thought so. There is a clip below. Listen to it. That is the Stax sound and it’s right up there with Chartres Cathedral and Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos as far as I’m concerned.

Gould does acknowledge in the afterword that his perspective on Stax Records might be quite different to that of Rob Bowman, Robert Gordon, and Peter Gurlanick, who have all written books on the subject. The difference is that they like the music. He lost me when he dismissed Eddie Floyd as a ‘journeyman’. A few years ago, I saw Floyd, who is no longer a young man, take the roof off a St Kilda venue and send it frisbee-like into Port Phillip Bay. He may not be Gould’s cup of tea but he is no journeyman. I also dispute that Steve Cropper’s guitar work is ‘limpid’ on Redding’s version of ‘A Change is Going To Come’ or any other song. Ever.

If you’ve already read the standard Stax Records books (see my list below), most of which cover Otis at great length, there are still many good reasons to read A Life Unfinished. The research is impeccable and perhaps it is time for a serious biography that goes beyond the music and addresses the wider implications of Otis Redding’s time on earth. Gould works hard to penetrate the somewhat mysterious inner life of the man. This is by no means some kind of iconoclastic Albert Goldman style biography but we are certainly left with a sense that there was a lot more to Otis than the genial image projected by his music.

If you’ve already read the standard Stax Records books (see my list below), most of which cover Otis at great length, there are still many good reasons to read A Life Unfinished. The research is impeccable and perhaps it is time for a serious biography that goes beyond the music and addresses the wider implications of Otis Redding’s time on earth. Gould works hard to penetrate the somewhat mysterious inner life of the man. This is by no means some kind of iconoclastic Albert Goldman style biography but we are certainly left with a sense that there was a lot more to Otis than the genial image projected by his music.

I like a music biography that sends me charging to my stereo or laptop to hear a particular version of a song or an album that I’ve henceforth ignored. This didn’t happen but perhaps Gould felt that book had already been written – and he’s right. If you’re after an account of Otis Redding’s life that skips the myth and aims to deliver the man himself along with the period he lived in, this might be the one.

Teasers: Otis and James Brown; Otis and Aretha; Otis’ serious brush with the law just as his career was taking off.

The Greatest Moment in Western Culture:

The evidence:

Further Reading on Stax Records, Otis, Southern Soul, etc:

It Came From Memphis by Robert Gordon (2001)

Sweet Soul Music by Peter Guralnick (1999)

Soulsville USA by Rob Bowman (2003)

Respect Yourself by Robert Gordon (2015)

Nowhere To Run by Gerri Hirshey (1994)

Say It One Time For The Broken Hearted By Barney Hoskyns (1998)

Dreams To Remember by Mark Ribowsky (2016)

Homeward Bound: The Life of Paul Simon by Peter Ames Carlin, Henry Holt, 2016

Homeward Bound: The Life of Paul Simon by Peter Ames Carlin, Henry Holt, 2016

It didn’t last long. Around 1970, Art’s involvement in the Catch 22 film proved too much for Simon’s fragile ego. He went solo, sank into depression when his first album only sold 2 million copies, and finally phoned up Artie to appear with him on the second ever episode of Saturday Night Live. “So, you came crawling back?” he said. The reunion lasted for one glorious song, My Little Town.

It didn’t last long. Around 1970, Art’s involvement in the Catch 22 film proved too much for Simon’s fragile ego. He went solo, sank into depression when his first album only sold 2 million copies, and finally phoned up Artie to appear with him on the second ever episode of Saturday Night Live. “So, you came crawling back?” he said. The reunion lasted for one glorious song, My Little Town.

And that brings us to Graceland. This is where the book really takes flight. What a story! Graceland was an album that I loathed with an almost exquisite fervour when it appeared in 1986. It sounded like BMW coke music, the kind of thing Gordon Gecko would have in his car. Man, the 80s were awful. Don’t let anyone tell you differently, kids. Simon predictably ran into trouble when he went to South Africa and recorded with a group of mbaqanga musicians that he first heard on a cassette that he forgot to give back to Heidi Berg. Before he even got around to his usual shenanigans with writing credits, he was in trouble with the ANC and found himself on a UN blacklist of musicians who had broken the embargo against working in South Africa.

And that brings us to Graceland. This is where the book really takes flight. What a story! Graceland was an album that I loathed with an almost exquisite fervour when it appeared in 1986. It sounded like BMW coke music, the kind of thing Gordon Gecko would have in his car. Man, the 80s were awful. Don’t let anyone tell you differently, kids. Simon predictably ran into trouble when he went to South Africa and recorded with a group of mbaqanga musicians that he first heard on a cassette that he forgot to give back to Heidi Berg. Before he even got around to his usual shenanigans with writing credits, he was in trouble with the ANC and found himself on a UN blacklist of musicians who had broken the embargo against working in South Africa.

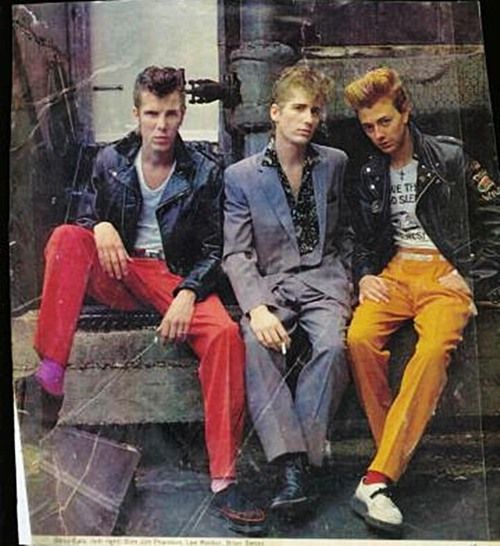

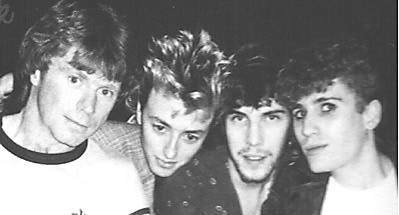

A Stray Cat Struts: My Life as a Rockabilly Rebel by Slim Jim Phantom, Thomas Dunne, 2016

A Stray Cat Struts: My Life as a Rockabilly Rebel by Slim Jim Phantom, Thomas Dunne, 2016

Which brings me to The Stray Cats, a band featuring vocalist and twangmaster Brian Setzer and ably rhythm sectioned by his Long Island high school chums Lee Rocker and our author, Slim Jim Phantom.

Which brings me to The Stray Cats, a band featuring vocalist and twangmaster Brian Setzer and ably rhythm sectioned by his Long Island high school chums Lee Rocker and our author, Slim Jim Phantom.

What does one say about a memoir like this one? It’s a bit of mess in terms of chronology and anyone looking for a detailed account of The Stray Cats’ career will want to look elsewhere. In fact, there’s not much about The Stray Cats at all. I would have been very curious to hear about the recording of those early albums and what it was like to work with Dave Edmunds. Perhaps Brian Setzer will cover that if he ever writes a book. There is a bit about their sound but never enough to really satisfy. Just when you think he is about to double down on the band that made him famous, he’s back in a club with Michael J Fox or someone.

What does one say about a memoir like this one? It’s a bit of mess in terms of chronology and anyone looking for a detailed account of The Stray Cats’ career will want to look elsewhere. In fact, there’s not much about The Stray Cats at all. I would have been very curious to hear about the recording of those early albums and what it was like to work with Dave Edmunds. Perhaps Brian Setzer will cover that if he ever writes a book. There is a bit about their sound but never enough to really satisfy. Just when you think he is about to double down on the band that made him famous, he’s back in a club with Michael J Fox or someone. Teasers: Slim Jim’s Rules of Rock and Roll are a highlight. Number Four is: “Always wear something around your waist that has nothing to do with holding your pants up.” Noted!

Teasers: Slim Jim’s Rules of Rock and Roll are a highlight. Number Four is: “Always wear something around your waist that has nothing to do with holding your pants up.” Noted! These Are The Days: Stories and Songs by Mick Thomas, Melbourne Books, 2017

These Are The Days: Stories and Songs by Mick Thomas, Melbourne Books, 2017

I was particularly struck by the chapter on Sisters of Mercy. This song from Weddings Parties Anything’s Roaring Days album was written in response to a nurses’ strike in the 1980s. In 2012 he was invited to play it for a large group of nurses at a strike meeting in the Melbourne Convention Centre. This chapter might have been a straightforward story about the song and how things never change. But it wasn’t. Instead, Thomas talks about a critique he’d copped in another setting for overdoing the emotional dimension of a song about asbestos poisoning. He was accused of emphasising the victimhood of the sufferers instead of celebrating their fighting spirit. The charge seemed terribly unfair and few singers would have the courage to revisit such a hardline dressing down. Mick then finds himself playing Sisters of Mercy for the striking nurses and choking back tears so as to avoid a repeat of the asbestos song episode. He manages it but only just. My own eyes grew a bit misty reading this chapter. The idea of a singer at a strike meeting in these cynical times is itself moving!

I was particularly struck by the chapter on Sisters of Mercy. This song from Weddings Parties Anything’s Roaring Days album was written in response to a nurses’ strike in the 1980s. In 2012 he was invited to play it for a large group of nurses at a strike meeting in the Melbourne Convention Centre. This chapter might have been a straightforward story about the song and how things never change. But it wasn’t. Instead, Thomas talks about a critique he’d copped in another setting for overdoing the emotional dimension of a song about asbestos poisoning. He was accused of emphasising the victimhood of the sufferers instead of celebrating their fighting spirit. The charge seemed terribly unfair and few singers would have the courage to revisit such a hardline dressing down. Mick then finds himself playing Sisters of Mercy for the striking nurses and choking back tears so as to avoid a repeat of the asbestos song episode. He manages it but only just. My own eyes grew a bit misty reading this chapter. The idea of a singer at a strike meeting in these cynical times is itself moving!

All is Given: A Memoir in Songs by Linda Neil, University of Queensland Press, 2016

All is Given: A Memoir in Songs by Linda Neil, University of Queensland Press, 2016

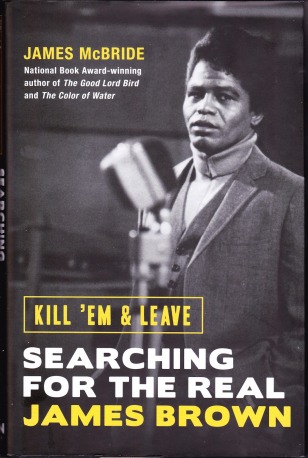

Kill ’Em And Leave: Searching for James Brown and the American Soul by James McBride, Spiegel & Grau 2016

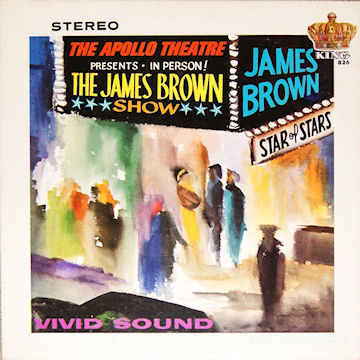

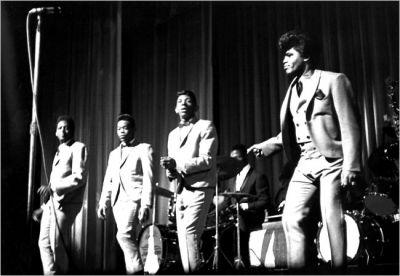

Kill ’Em And Leave: Searching for James Brown and the American Soul by James McBride, Spiegel & Grau 2016 I have only ever been a casual fan of James Brown. Like everyone else, I have owned Live at the Apollo in at least four formats, along with a greatest hits collection purchased during a brief teenage Mod phase. I saw him once too. In the mid 80s he played the Ontario Place Forum in Toronto with its revolving stage. It was a strange show. He did about five songs. Two of them were It’s A Man’s World. Then he came out with the cape, etc, for an encore. You guessed it, It’s A Man’s World one more time. I walked out of there like Robert Bly with a six-pack.

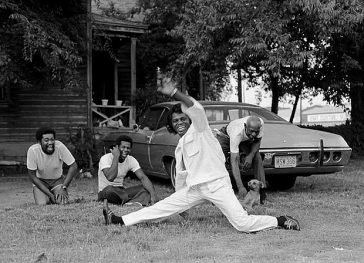

I have only ever been a casual fan of James Brown. Like everyone else, I have owned Live at the Apollo in at least four formats, along with a greatest hits collection purchased during a brief teenage Mod phase. I saw him once too. In the mid 80s he played the Ontario Place Forum in Toronto with its revolving stage. It was a strange show. He did about five songs. Two of them were It’s A Man’s World. Then he came out with the cape, etc, for an encore. You guessed it, It’s A Man’s World one more time. I walked out of there like Robert Bly with a six-pack. James McBride’s provocative account of Brown’s career makes one thing clear. The self styled Godfather of Soul does not fit easily into the received story of rock and roll. Motown makes sense. The Beatles drew from Motown. Chess makes sense. The Rolling Stones found something there. But James Brown’s legacy, in rock and roll at least, is less obvious. The story of his upstaging of the Stones is famous. Keith Richards has said that trying to follow him was the dumbest thing the band ever did. Brown, by some accounts, begat funk which begat disco. Okay, but we’re still talking about tributaries that exist outside of the rock and roll critical river. James McBride’s point here is never stated explicitly but his meaning is clear. James Brown is central to the African American experience of popular music. The standard Elvis – Beatles – Bowie – Punk – and so on story is arguably a very white one that, while not excluding black music, does sideline it. Elijah Wald explored this theme in his book How The Beatles Destroyed Rock and Roll a few years ago. James Brown’s story is certainly illustrative of it. If you’re shaking your head, think about this: The Beatles have appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone more than 30 times. James Brown, one of the key innovators in popular music, has appeared twice. The first time, in 1989, was well after his heyday and the second time, 2006, was after his death.

James McBride’s provocative account of Brown’s career makes one thing clear. The self styled Godfather of Soul does not fit easily into the received story of rock and roll. Motown makes sense. The Beatles drew from Motown. Chess makes sense. The Rolling Stones found something there. But James Brown’s legacy, in rock and roll at least, is less obvious. The story of his upstaging of the Stones is famous. Keith Richards has said that trying to follow him was the dumbest thing the band ever did. Brown, by some accounts, begat funk which begat disco. Okay, but we’re still talking about tributaries that exist outside of the rock and roll critical river. James McBride’s point here is never stated explicitly but his meaning is clear. James Brown is central to the African American experience of popular music. The standard Elvis – Beatles – Bowie – Punk – and so on story is arguably a very white one that, while not excluding black music, does sideline it. Elijah Wald explored this theme in his book How The Beatles Destroyed Rock and Roll a few years ago. James Brown’s story is certainly illustrative of it. If you’re shaking your head, think about this: The Beatles have appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone more than 30 times. James Brown, one of the key innovators in popular music, has appeared twice. The first time, in 1989, was well after his heyday and the second time, 2006, was after his death. McBride himself tasted literary stardom a few years ago with his memoir, The Color of Water. He is a formidable prose writer who has also worked as a professional musician. It’s not surprising that this book made so many ‘best of’ lists for 2016. As one era in the White House ends and we await the full implications of the one that will follow, McBride’s story of a man who scored his first hit in 1956 couldn’t be more relevant. The search for the soul of America is ongoing.

McBride himself tasted literary stardom a few years ago with his memoir, The Color of Water. He is a formidable prose writer who has also worked as a professional musician. It’s not surprising that this book made so many ‘best of’ lists for 2016. As one era in the White House ends and we await the full implications of the one that will follow, McBride’s story of a man who scored his first hit in 1956 couldn’t be more relevant. The search for the soul of America is ongoing. Born To Run by Bruce Springsteen, Simon & Schuster 2016

Born To Run by Bruce Springsteen, Simon & Schuster 2016 But this is Bruce himself. He is articulate in interviews and his gift with language has never been in doubt. Many of his songs involve narratives, sometimes personal, but what would a book length Springsteen ‘song’ look like? As it turns out, pretty good. This man can write. At times, particularly in the early sections, it occurred to me that he had a distinctly ‘American’ style of the old school. Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward Angel came to mind. So did James T Farrell’s Studs Lonigan trilogy. The scenes with his father place him a very long tradition in American letters.

But this is Bruce himself. He is articulate in interviews and his gift with language has never been in doubt. Many of his songs involve narratives, sometimes personal, but what would a book length Springsteen ‘song’ look like? As it turns out, pretty good. This man can write. At times, particularly in the early sections, it occurred to me that he had a distinctly ‘American’ style of the old school. Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward Angel came to mind. So did James T Farrell’s Studs Lonigan trilogy. The scenes with his father place him a very long tradition in American letters. Born To Run is also miles away from Keith Richards’ engaging if slightly tiresome Life. There are no ‘then the groupies brought more coke’ moments or anything even approaching that kind of rock and roll story. At some point in the late 70s, Jimmy Iovine invited Bruce to the Playboy Mansion. No one, surely, would have begrudged a young rock and roll star an evening with Hugh and his pals but Bruce declined. No thanks, Jimmy, it’s just not me.

Born To Run is also miles away from Keith Richards’ engaging if slightly tiresome Life. There are no ‘then the groupies brought more coke’ moments or anything even approaching that kind of rock and roll story. At some point in the late 70s, Jimmy Iovine invited Bruce to the Playboy Mansion. No one, surely, would have begrudged a young rock and roll star an evening with Hugh and his pals but Bruce declined. No thanks, Jimmy, it’s just not me. So what else do we learn? A few interesting items are revealed but here’s one that struck me: Bruce, it would appear, has a lot of affection for The River LP. He spends a lot of time on this album in the book. He rejected the original Bob Clearmountain mixed single LP because he wanted something a bit more ragged and more representative of the true E Street Band sound. There are personal clouds over most of his other classic albums but The River appears to be a record where he feels he got it right.

So what else do we learn? A few interesting items are revealed but here’s one that struck me: Bruce, it would appear, has a lot of affection for The River LP. He spends a lot of time on this album in the book. He rejected the original Bob Clearmountain mixed single LP because he wanted something a bit more ragged and more representative of the true E Street Band sound. There are personal clouds over most of his other classic albums but The River appears to be a record where he feels he got it right. Teasers: Frank Sinatra’s birthday party with Bob Dylan in attendance; Less about Clarence and Miami Steve than you might expect, but a lot about Danny Federici and Vinny Lopez, original E Streeters with their own stories. Also, Bruce’s take on his ’80s image – “I looked…gay!”

Teasers: Frank Sinatra’s birthday party with Bob Dylan in attendance; Less about Clarence and Miami Steve than you might expect, but a lot about Danny Federici and Vinny Lopez, original E Streeters with their own stories. Also, Bruce’s take on his ’80s image – “I looked…gay!”

As if to make this plain, the first section deals with the ‘myth’ and, specifically, the autobiography Holiday produced in 1957. Lady Sings the Blues was much read at the time but is a book that has always been considered fictitious. He points out that she was forced to suppress the sections that dealt with many of her friendships and romantic relationships. Orson Welles, Charles Laughton, Tallulah Bankhead, Elizabeth Bishop, and several other notables threatened legal action if they were mentioned. Billie’s problems with heroin and her troubles with the law were both well known by the 1950s. No one wanted to be publicly associated with her. The book then became a hodgepodge of stories that emphasized her troubled life. Szwed suggests that the book isn’t fictitious, just incomplete. Like all biographical writing, it reflects the values of the period in which it was written. There is a glut of rock and roll memoirs on the shelves in bookstores at the moment. The selling point is, of course, the opportunity to hear the ‘true’ story from the horse’s mouth. Billie’s autobiography is a reminder that the ‘truth’ is no simple matter.

As if to make this plain, the first section deals with the ‘myth’ and, specifically, the autobiography Holiday produced in 1957. Lady Sings the Blues was much read at the time but is a book that has always been considered fictitious. He points out that she was forced to suppress the sections that dealt with many of her friendships and romantic relationships. Orson Welles, Charles Laughton, Tallulah Bankhead, Elizabeth Bishop, and several other notables threatened legal action if they were mentioned. Billie’s problems with heroin and her troubles with the law were both well known by the 1950s. No one wanted to be publicly associated with her. The book then became a hodgepodge of stories that emphasized her troubled life. Szwed suggests that the book isn’t fictitious, just incomplete. Like all biographical writing, it reflects the values of the period in which it was written. There is a glut of rock and roll memoirs on the shelves in bookstores at the moment. The selling point is, of course, the opportunity to hear the ‘true’ story from the horse’s mouth. Billie’s autobiography is a reminder that the ‘truth’ is no simple matter.