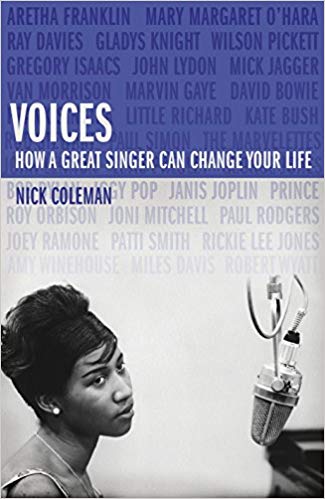

Voices: How a Singer Can Change Your Life by Nick Coleman, Jonathan Cape 2018

Voices: How a Singer Can Change Your Life by Nick Coleman, Jonathan Cape 2018

“Yeah, but he’s a terrible singer.”

And then they always intone a nasally ‘how does it feeeeel?’ just in case I don’t know that song or haven’t recognized that Dylan doesn’t sing like Sarah Vaughan.

If you’re a Dylan fan, you know this scenario. It’s so predictable that it barely registers. I’m never sure what to say, other than the obvious: Compared to whom? Bob is always singled out for something fairly unexceptional in rock and roll. It’s as though everyone in popular music has a great voice except Bob. Sure they do…

I’m listening to Mazzy Star’s first album right now as I write because I was listening to the Cowboy Junkies this morning. I was listening to Townes when I thought of the Cowboy Junkies. Townes, Margo, Hope. None of them are brilliant singers in any technical sense but then, what does that mean? I love their voices and would listen to all of them sing the phone book before I would waste 10 seconds listening to a lot of people who are considered ‘great’ singers. So would you!

The only terrible singer in rock and roll

My son is that age where he is appalled by other people’s bad taste and lack of knowledge about music. Some kid in his class has never heard of Hendrix and prefers some rap star anyway! Another thinks Ariana Grande is better than Janis! My message to him is to respect others’ taste in music. If it brings them joy, it’s okay. I’m stating the obvious but your taste in music is simply that: your taste in music. You might have some authority because you’ve heard a lot of stuff but the fact is that music either moves you or it doesn’t. There isn’t a scale by which we can measure a rock and roll band’s aesthetic value. The Stooges are great but they are not objectively better than The Monkees (I want to qualify that sentence so badly that my teeth are aching. I can’t stand The Monkees).

Musical taste is personal. So what? Well, In Nick Coleman’s Voices: How a Singer Can Change Your Life, he suggests our response to the voice might be the most personal of all our tastes. This intriguing new book is a meditation on singers and singing. His contention is that we can be objective about instrumental music to an extent but voices are too embedded in our consciousness to be anything but a zero sum game. We like them or we don’t. When we were babies we heard voices. We didn’t understand the words but we got very good at hearing what they were expressing. Love, frustration, humor, concern, and anger were all conveyed to us initially through the sound of a voice. Thus our response is primal. If people had only played tenor saxophones to us from birth we might feel the same way about woodwinds. Not a bad idea!

Accent!

The book is built around a series of categories that form the chapters. One or two singers might be the main exemplars of something like ‘Accent’ (Mick Jagger and John Lennon) but Coleman uses a broad range of examples to illustrate his point. At the end of each chapter, there is a section called ‘Grace Notes’ where he looks at specific songs that have this quality (Waterloo Sunset for ‘Accent’) Some of the other categories are ‘Identification’, ‘Soul’, and ‘Croon’. Ronnie Spector, Wilson Pickett, and, interestingly, Gregory Isaacs respectively get a lot of attention in those chapters.

Because singing and our response to singers is demonstrably close to our hearts, the book is personal. Coleman makes it clear that he is speaking from a particular context (East Anglia) and as someone of a certain age. At 58, he is part of that little group that slips between the boomers and GenX. He came of age listening to prog and had his mind blown by punk. His story about hearing Anarchy in the UK for the first time is funny. His story about a friend having a panic attack listening to Joy Division’s Closer (Anguish) is harrowing. The 80s did little for him although he adores Hounds of Love (Croon). Coleman is a thoughtful listener with a vast knowledge of popular music. I always judge a music book by how many times I stopped reading to listen to something. It took me a long time to get through this one.

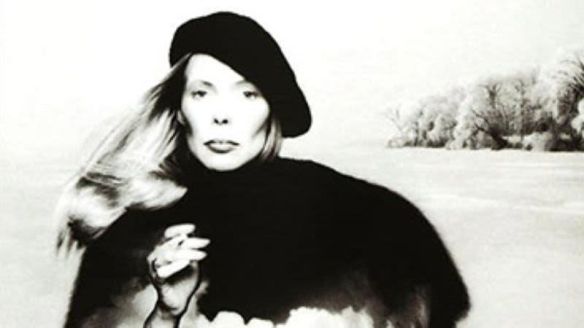

Sophisticated and Restless

The real power of Voices, however, is in Coleman’s enviable ability to describe the sonic quality of the voice in music. He digs deep into the implications of the performance and finds hidden elements in a wide range of songs, both familiar and obscure. In the ‘Sophistication’ section he draws out something akin to restlessness in Joni Mitchell’s Song for Sharon. I have to say that the discussion of Joni’s work here struck me as far more insightful than anything in the most recent biography. Marvin Gaye’s voice is explored under the banner of ‘Vulnerability’ with his singular Here My Dear album as an example. Coleman compares this strange record to Rogier Van der Weyden’s 15th century masterpiece, The Descent from the Cross. The painting (see below) uses a frame to call attention to its own limitations: the cosmic dimensions of the event defeats its human and artistic capacity. Coleman sees Here My Dear in a similar light. Gaye’s voice suggests that there is simply too much to express. That is, according to Coleman, the very definition of vulnerability.

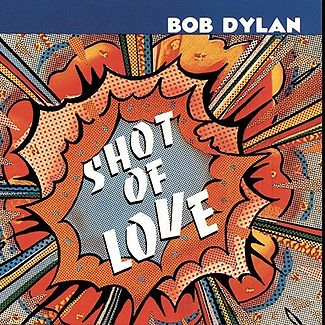

Things get very interesting indeed in the final chapter on Rapture and Psalms. Van Morrison’s career is compared to Bede’s reluctant singer, Caedmon, the singer who nonetheless finds his voice and his song. Coleman hears something of this rapture on the Moondance album, in particular. A discussion of the Psalms is followed by a consideration of ‘voices in the wilderness’ and the rather surprising example of John Lydon and PIL’s Metal Box. Burning Spear’s Marcus Garvey album is also covered here. Bob Dylan makes an appearance in the Grace Notes section of Rapture and Psalms. Coleman doesn’t bother too much with Dylan (or Neil Young, intriguingly) in this book but it makes sense that the laureate would turn up in this section. I thought something from Slow Train Coming might be covered but Coleman talks about No More Auction Block and Blind Willie McTell, two songs that are probably not familiar to the sort of person who does lame imitations of Bob but are well worth hearing!

Steve Marriott

Clearly, I enjoyed Voices but I have one serious bone to pick with it. Here it is: Steve Marriott is a better singer than Paul Rodgers, Long John Baldry, Tom Jones, Phil May, Roger Daltrey and all the other British singers mentioned in this section. Marriott is a locomotive among Mini Coopers here. No one in rock and roll even comes close. Coleman, however, reduces him to someone who was okay in the sixties but really sucked in Humble Pie. Meanwhile, I’m supposed to believe that Rod Stewart was some kind of soul god. Dude, please.

You see! It always gets personal with voices. If you think Coltrane is overrated, we can talk. If you think Billie Holiday is overrated, I’m outta here. This is a fascinating book that will force you into entrenched positions like mine on Marriott but also demand that you think a bit about them. It is also a book that tries to understand what it is about music and humans. Yes, he drifts into a brief discussion of brain chemistry; the new black for books about anything at all, but fortunately concludes that it doesn’t really answer any questions about music.

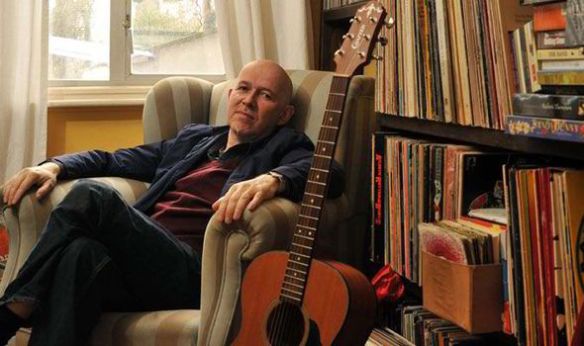

The epilogue to this book is terribly sad. If you’ve read his previous book, The Train in the Night, you know that he has essentially gone deaf, a cruel fate for a music critic and someone with Coleman’s obvious passion. There is some good news, mixed with some setbacks here. I was particularly moved by the section where he recovers some of his hearing and devours as much music as he can in case it doesn’t last. A reminder for all of us perhaps that there are a lot of songs to get through in this life. Music, as Coleman rightly points out, is a complicated pleasure and it’s one that we should never take for granted.

Nick Coleman

With that in mind, who are your favourite singers and why? For the Coleman challenge, pick a particular song and try to describe the sound of the voice itself. Not easy!

Teasers: The best defense of Mick Jagger’s voice you will ever read. John Lennon’s loathing of his own voice – plus the truly primal scream of his Twist and Shout. Also, Frankie Miller, a truly underrated voice.

Also discussed in the book, of course! Roy Orbison:

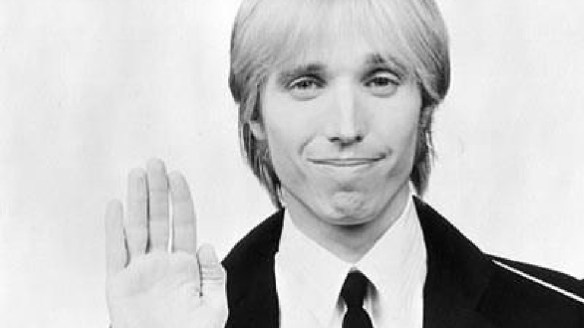

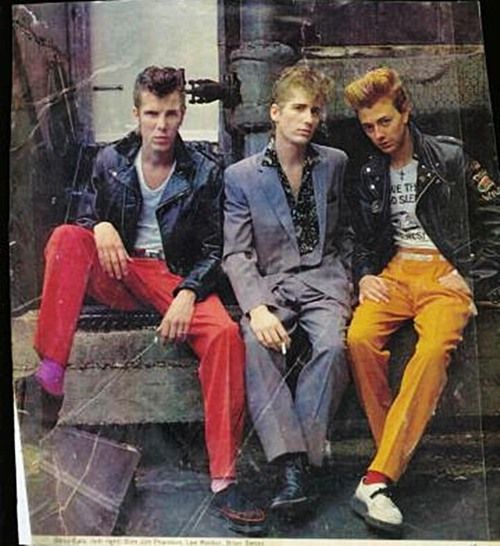

Tom who? Rod who? Steve Marriott in The Small Faces:

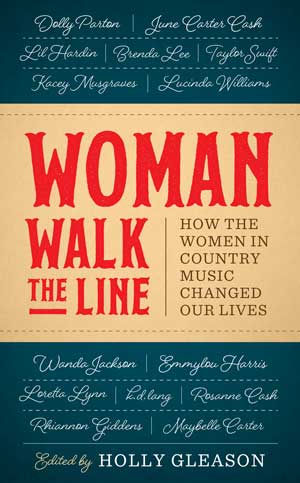

Woman* Walk The Line: How the Women in Country Music Changed Our Lives by Holly Gleason (editor), University of Texas Press 2017

Woman* Walk The Line: How the Women in Country Music Changed Our Lives by Holly Gleason (editor), University of Texas Press 2017

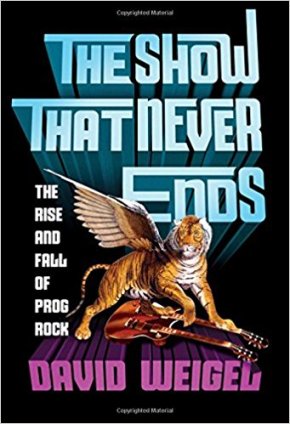

The Show That Never Ends: The Rise and Fall of Prog Rock by David Weigel, WW Norton & Co, 2016

The Show That Never Ends: The Rise and Fall of Prog Rock by David Weigel, WW Norton & Co, 2016 Weigel manages to produce a serious history of Prog without turning it into Das Kapital. He is a big fan but he also understands that there is something innately funny about the genre. Pomposity was one of its hallmarks in the manner that nihilistic aggression was part of punk. That is to say, it was pompous but unapologetically so. Naturally, Prog became something of a punchline. This was, after all a genre where one band (Magma) made up its own language (Kobaian). Rock critics hated it. They took the first few albums on their own merits – Lester Bangs liked Yes’s first album, for example – but shot each subsequent release down like wooden ducks on the midway. Remember that these writers, for the most part, found Led Zeppelin pretentious. Imagine what they thought when Rick Wakeman’s The Six Wives of Henry VIII turned up for review. When Emerson Lake and Palmer released Trilogy in 1972, Robert Christgau wrote: “The pomposities of Tarkus and the monstrosities of the Mussorgsky homage clinch it–these guys are as stupid as their most pretentious fans. Really, anybody who buys a record that divides a composition called “The Endless Enigma” into two discrete parts deserves it.” Still, for a little while, Prog went over like horses with the record buying and concert attending public. The most popular band of today wouldn’t dare to dream of selling a tenth of what a lesser Kansas record would have in the 70s.

Weigel manages to produce a serious history of Prog without turning it into Das Kapital. He is a big fan but he also understands that there is something innately funny about the genre. Pomposity was one of its hallmarks in the manner that nihilistic aggression was part of punk. That is to say, it was pompous but unapologetically so. Naturally, Prog became something of a punchline. This was, after all a genre where one band (Magma) made up its own language (Kobaian). Rock critics hated it. They took the first few albums on their own merits – Lester Bangs liked Yes’s first album, for example – but shot each subsequent release down like wooden ducks on the midway. Remember that these writers, for the most part, found Led Zeppelin pretentious. Imagine what they thought when Rick Wakeman’s The Six Wives of Henry VIII turned up for review. When Emerson Lake and Palmer released Trilogy in 1972, Robert Christgau wrote: “The pomposities of Tarkus and the monstrosities of the Mussorgsky homage clinch it–these guys are as stupid as their most pretentious fans. Really, anybody who buys a record that divides a composition called “The Endless Enigma” into two discrete parts deserves it.” Still, for a little while, Prog went over like horses with the record buying and concert attending public. The most popular band of today wouldn’t dare to dream of selling a tenth of what a lesser Kansas record would have in the 70s.

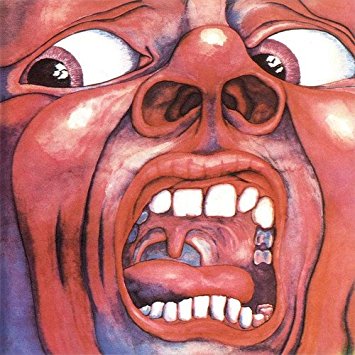

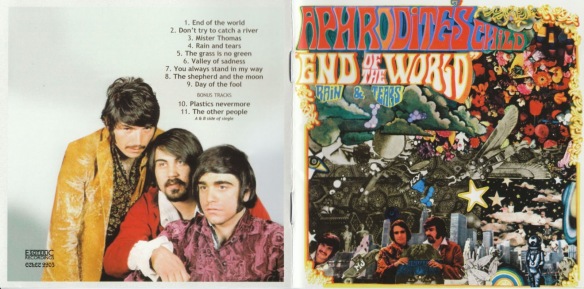

The next big challenge is finding a starting point. Weigel begins with The Moody Blues, Procol Harum, The Nice, and Pink Floyd. He mentions The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper which I think may have given permission for some of the high concept psychedelia that followed. The Who’s Tommy, The Small Faces’ Odgen’s Nut Gone Flake, and The Zombies’ Odessey and Oracle come to mind. I was surprised that The Pretty Things’ SF Sorrow didn’t rate a mention. Weigel more or less settles on The Moody Blues’ Days of Future Passed and King Crimson’s In the Court of the Crimson King as the point of lift off. Naturally, some of the other bands had false starts. The first Genesis album is a lot closer to Cucumber Castle than most Prog fans would care to admit. Just over two years later, they recorded Supper’s Ready, a 23 minute masterpiece or nightmare, depending on your perspective. Either way, it is Prog’s answer to The Wasteland. How’s that for a big call?

The next big challenge is finding a starting point. Weigel begins with The Moody Blues, Procol Harum, The Nice, and Pink Floyd. He mentions The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper which I think may have given permission for some of the high concept psychedelia that followed. The Who’s Tommy, The Small Faces’ Odgen’s Nut Gone Flake, and The Zombies’ Odessey and Oracle come to mind. I was surprised that The Pretty Things’ SF Sorrow didn’t rate a mention. Weigel more or less settles on The Moody Blues’ Days of Future Passed and King Crimson’s In the Court of the Crimson King as the point of lift off. Naturally, some of the other bands had false starts. The first Genesis album is a lot closer to Cucumber Castle than most Prog fans would care to admit. Just over two years later, they recorded Supper’s Ready, a 23 minute masterpiece or nightmare, depending on your perspective. Either way, it is Prog’s answer to The Wasteland. How’s that for a big call?

I must admit that, Pink Floyd and Jethro Tull aside, I have never been a great fan of this stuff. While reading the book, however, I discovered some wonderful King Crimson albums I’d never heard and finally picked up Robert Wyatt’s Rock Bottom. I even spun Emerson Lake and Palmer’s first record one night. Lucky Man brought back good memories of summer camp in the 1970s. I was struck by a sense that this music was more a part of my childhood than I thought. However, Gabriel-era Genesis remains too freaky for me. I have a complicated and slightly scary story about why I don’t listen to them but I’ll save that for when Peter Gabriel writes a memoir.

I must admit that, Pink Floyd and Jethro Tull aside, I have never been a great fan of this stuff. While reading the book, however, I discovered some wonderful King Crimson albums I’d never heard and finally picked up Robert Wyatt’s Rock Bottom. I even spun Emerson Lake and Palmer’s first record one night. Lucky Man brought back good memories of summer camp in the 1970s. I was struck by a sense that this music was more a part of my childhood than I thought. However, Gabriel-era Genesis remains too freaky for me. I have a complicated and slightly scary story about why I don’t listen to them but I’ll save that for when Peter Gabriel writes a memoir.

Trouble In Mind: Bob Dylan’s Gospel Period – What Really Happened by Clinton Heylin, 2017

Trouble In Mind: Bob Dylan’s Gospel Period – What Really Happened by Clinton Heylin, 2017

The first, Slow Train Coming, is surely one of Bob Dylan’s finest moments. After a dry spell in the early 70s, Bob began to write from a more personal place. His ability with imagery remained but he left behind the Beat babble for lyrics that seemed to come from a deeper source. The older I get, the more difficult I find it to listen to the raw pain on 1975’s Blood on the Tracks. Street Legal (1978) is, for me, on par with Neil Young’s Time Fades Away. It sounds like a ragged cry of bewilderment. Slow Train thus sounds like an answer, of sorts. The songs are beautifully constructed and feature little of the obfuscation that Dylan was so well known for at the time.

The first, Slow Train Coming, is surely one of Bob Dylan’s finest moments. After a dry spell in the early 70s, Bob began to write from a more personal place. His ability with imagery remained but he left behind the Beat babble for lyrics that seemed to come from a deeper source. The older I get, the more difficult I find it to listen to the raw pain on 1975’s Blood on the Tracks. Street Legal (1978) is, for me, on par with Neil Young’s Time Fades Away. It sounds like a ragged cry of bewilderment. Slow Train thus sounds like an answer, of sorts. The songs are beautifully constructed and feature little of the obfuscation that Dylan was so well known for at the time. It took me years to finally sit down and listen to the second album in the series, Saved. The original cover art was confronting and the stridency of the Christian messages stung critics who felt as though they’d allowed him a free pass on one religious record already. The negative reviews in retrospect seem to be all about discomfort with the lyrics and the context of the album, rather than the music. I wonder how many people, like me, went running home to listen to it after hearing John Doe’s version of Pressing On in Todd Haynes’ film, I’m Not There. I suspect many found a far better album than they expected. I sure did!

It took me years to finally sit down and listen to the second album in the series, Saved. The original cover art was confronting and the stridency of the Christian messages stung critics who felt as though they’d allowed him a free pass on one religious record already. The negative reviews in retrospect seem to be all about discomfort with the lyrics and the context of the album, rather than the music. I wonder how many people, like me, went running home to listen to it after hearing John Doe’s version of Pressing On in Todd Haynes’ film, I’m Not There. I suspect many found a far better album than they expected. I sure did!

The Traveling Wilburys: The Biography by Nick Thomas, Guardian Express Media (E-Book) 2017

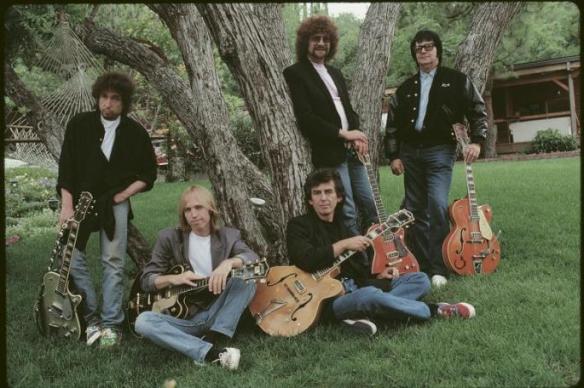

The Traveling Wilburys: The Biography by Nick Thomas, Guardian Express Media (E-Book) 2017 About 8 months later, a 13 year old boy called Tom Petty in Gainesville Florida was watching The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show, completely unaware that he would one day form a band with the shy fellow playing a Gretsch Country Gentleman. Four or five months after that, in the summer of 1964, George and his band mates were supposedly introduced to marijuana (Rock and Roll myth #540: They didn’t come across weed in Hamburg? Yeah right!) by a chatty fellow from Minnesota named Bob Dylan. As they puffed away in the Delmonico Hotel, Bob probably didn’t foresee the day when he would accept an invitation to join George Harrison’s band.

About 8 months later, a 13 year old boy called Tom Petty in Gainesville Florida was watching The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show, completely unaware that he would one day form a band with the shy fellow playing a Gretsch Country Gentleman. Four or five months after that, in the summer of 1964, George and his band mates were supposedly introduced to marijuana (Rock and Roll myth #540: They didn’t come across weed in Hamburg? Yeah right!) by a chatty fellow from Minnesota named Bob Dylan. As they puffed away in the Delmonico Hotel, Bob probably didn’t foresee the day when he would accept an invitation to join George Harrison’s band.

Thomas’s book makes no special claims for the songs on the album. They were written quickly by a group of very experienced songwriters throwing out lines to each other. Lyrically speaking, nothing on either record is a patch on any of the members’ own work, your feelings about ELO notwithstanding. But this record is all about atmosphere and sound. George Harrison’s lovely guitar work; Roy’s otherworldly voice; Dylan’s strangeness; and Petty’s punk rock sneer all combine here for something very special. Jeff Lynne adds his acoustic wall of sound and old school rockabilly sensibility for the icing on an estimable cake.

Thomas’s book makes no special claims for the songs on the album. They were written quickly by a group of very experienced songwriters throwing out lines to each other. Lyrically speaking, nothing on either record is a patch on any of the members’ own work, your feelings about ELO notwithstanding. But this record is all about atmosphere and sound. George Harrison’s lovely guitar work; Roy’s otherworldly voice; Dylan’s strangeness; and Petty’s punk rock sneer all combine here for something very special. Jeff Lynne adds his acoustic wall of sound and old school rockabilly sensibility for the icing on an estimable cake. For Tom Petty, October 20, 1950 – October 2, 2017

For Tom Petty, October 20, 1950 – October 2, 2017

Pickers and Poets: The Ruthlessly Poetic Singer-Songwriters of Texas by

Pickers and Poets: The Ruthlessly Poetic Singer-Songwriters of Texas by  I was sold when Willis Alan Ramsay turned up in one of the first essays. In the chapters that follow, it becomes clear that many songwriters continue to hold him in very high esteem. He recorded exactly one album in 1972. It sold poorly and disappeared almost immediately. But what a record! You’ll recognise one song on it. Yes, Willis Alan Ramsay wrote Muskrat Love and, what’s more, it’s a great song. His version, that is. He also wrote Angel Eyes, a song that you will either play or wish you had played at your wedding.

I was sold when Willis Alan Ramsay turned up in one of the first essays. In the chapters that follow, it becomes clear that many songwriters continue to hold him in very high esteem. He recorded exactly one album in 1972. It sold poorly and disappeared almost immediately. But what a record! You’ll recognise one song on it. Yes, Willis Alan Ramsay wrote Muskrat Love and, what’s more, it’s a great song. His version, that is. He also wrote Angel Eyes, a song that you will either play or wish you had played at your wedding.

The introduction includes a cringe-worthy explanation of why so few women are included but the chapter devoted exclusively to them is perhaps the best in the book. There are also chapters on newish singer songwriters like Kacey Musgraves and Terri Hendrix in the last section of the book. The whole thing, at times, seems edited by committee so perhaps they forgot. The chapter on Don Henley (yes, from Texas, shame about his anaemic music) was mercifully brief but still too long for this reader. The sections on figures like Steve Earle and Lucinda Williams contained far too much general information that is already widely available. The chapter on Rodney Crowell, on the other hand, was fascinating. Guy Clark seemed underplayed throughout the book though the essay by Tamara Saviano bodes well for her recent biography of the man. But these are just quibbles about an engaging and informative book. Any book on music that I have to put down so that I can listen to an artist or album that I don’t know gets high marks from me. It took me weeks to get through this one! Discovering David Rodriguez alone was worth the cover price.

The introduction includes a cringe-worthy explanation of why so few women are included but the chapter devoted exclusively to them is perhaps the best in the book. There are also chapters on newish singer songwriters like Kacey Musgraves and Terri Hendrix in the last section of the book. The whole thing, at times, seems edited by committee so perhaps they forgot. The chapter on Don Henley (yes, from Texas, shame about his anaemic music) was mercifully brief but still too long for this reader. The sections on figures like Steve Earle and Lucinda Williams contained far too much general information that is already widely available. The chapter on Rodney Crowell, on the other hand, was fascinating. Guy Clark seemed underplayed throughout the book though the essay by Tamara Saviano bodes well for her recent biography of the man. But these are just quibbles about an engaging and informative book. Any book on music that I have to put down so that I can listen to an artist or album that I don’t know gets high marks from me. It took me weeks to get through this one! Discovering David Rodriguez alone was worth the cover price.

Homeward Bound: The Life of Paul Simon by Peter Ames Carlin, Henry Holt, 2016

Homeward Bound: The Life of Paul Simon by Peter Ames Carlin, Henry Holt, 2016

It didn’t last long. Around 1970, Art’s involvement in the Catch 22 film proved too much for Simon’s fragile ego. He went solo, sank into depression when his first album only sold 2 million copies, and finally phoned up Artie to appear with him on the second ever episode of Saturday Night Live. “So, you came crawling back?” he said. The reunion lasted for one glorious song, My Little Town.

It didn’t last long. Around 1970, Art’s involvement in the Catch 22 film proved too much for Simon’s fragile ego. He went solo, sank into depression when his first album only sold 2 million copies, and finally phoned up Artie to appear with him on the second ever episode of Saturday Night Live. “So, you came crawling back?” he said. The reunion lasted for one glorious song, My Little Town.

And that brings us to Graceland. This is where the book really takes flight. What a story! Graceland was an album that I loathed with an almost exquisite fervour when it appeared in 1986. It sounded like BMW coke music, the kind of thing Gordon Gecko would have in his car. Man, the 80s were awful. Don’t let anyone tell you differently, kids. Simon predictably ran into trouble when he went to South Africa and recorded with a group of mbaqanga musicians that he first heard on a cassette that he forgot to give back to Heidi Berg. Before he even got around to his usual shenanigans with writing credits, he was in trouble with the ANC and found himself on a UN blacklist of musicians who had broken the embargo against working in South Africa.

And that brings us to Graceland. This is where the book really takes flight. What a story! Graceland was an album that I loathed with an almost exquisite fervour when it appeared in 1986. It sounded like BMW coke music, the kind of thing Gordon Gecko would have in his car. Man, the 80s were awful. Don’t let anyone tell you differently, kids. Simon predictably ran into trouble when he went to South Africa and recorded with a group of mbaqanga musicians that he first heard on a cassette that he forgot to give back to Heidi Berg. Before he even got around to his usual shenanigans with writing credits, he was in trouble with the ANC and found himself on a UN blacklist of musicians who had broken the embargo against working in South Africa.

A Stray Cat Struts: My Life as a Rockabilly Rebel by Slim Jim Phantom, Thomas Dunne, 2016

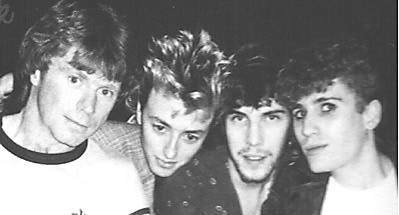

A Stray Cat Struts: My Life as a Rockabilly Rebel by Slim Jim Phantom, Thomas Dunne, 2016

Which brings me to The Stray Cats, a band featuring vocalist and twangmaster Brian Setzer and ably rhythm sectioned by his Long Island high school chums Lee Rocker and our author, Slim Jim Phantom.

Which brings me to The Stray Cats, a band featuring vocalist and twangmaster Brian Setzer and ably rhythm sectioned by his Long Island high school chums Lee Rocker and our author, Slim Jim Phantom.

What does one say about a memoir like this one? It’s a bit of mess in terms of chronology and anyone looking for a detailed account of The Stray Cats’ career will want to look elsewhere. In fact, there’s not much about The Stray Cats at all. I would have been very curious to hear about the recording of those early albums and what it was like to work with Dave Edmunds. Perhaps Brian Setzer will cover that if he ever writes a book. There is a bit about their sound but never enough to really satisfy. Just when you think he is about to double down on the band that made him famous, he’s back in a club with Michael J Fox or someone.

What does one say about a memoir like this one? It’s a bit of mess in terms of chronology and anyone looking for a detailed account of The Stray Cats’ career will want to look elsewhere. In fact, there’s not much about The Stray Cats at all. I would have been very curious to hear about the recording of those early albums and what it was like to work with Dave Edmunds. Perhaps Brian Setzer will cover that if he ever writes a book. There is a bit about their sound but never enough to really satisfy. Just when you think he is about to double down on the band that made him famous, he’s back in a club with Michael J Fox or someone. Teasers: Slim Jim’s Rules of Rock and Roll are a highlight. Number Four is: “Always wear something around your waist that has nothing to do with holding your pants up.” Noted!

Teasers: Slim Jim’s Rules of Rock and Roll are a highlight. Number Four is: “Always wear something around your waist that has nothing to do with holding your pants up.” Noted! These Are The Days: Stories and Songs by Mick Thomas, Melbourne Books, 2017

These Are The Days: Stories and Songs by Mick Thomas, Melbourne Books, 2017

I was particularly struck by the chapter on Sisters of Mercy. This song from Weddings Parties Anything’s Roaring Days album was written in response to a nurses’ strike in the 1980s. In 2012 he was invited to play it for a large group of nurses at a strike meeting in the Melbourne Convention Centre. This chapter might have been a straightforward story about the song and how things never change. But it wasn’t. Instead, Thomas talks about a critique he’d copped in another setting for overdoing the emotional dimension of a song about asbestos poisoning. He was accused of emphasising the victimhood of the sufferers instead of celebrating their fighting spirit. The charge seemed terribly unfair and few singers would have the courage to revisit such a hardline dressing down. Mick then finds himself playing Sisters of Mercy for the striking nurses and choking back tears so as to avoid a repeat of the asbestos song episode. He manages it but only just. My own eyes grew a bit misty reading this chapter. The idea of a singer at a strike meeting in these cynical times is itself moving!

I was particularly struck by the chapter on Sisters of Mercy. This song from Weddings Parties Anything’s Roaring Days album was written in response to a nurses’ strike in the 1980s. In 2012 he was invited to play it for a large group of nurses at a strike meeting in the Melbourne Convention Centre. This chapter might have been a straightforward story about the song and how things never change. But it wasn’t. Instead, Thomas talks about a critique he’d copped in another setting for overdoing the emotional dimension of a song about asbestos poisoning. He was accused of emphasising the victimhood of the sufferers instead of celebrating their fighting spirit. The charge seemed terribly unfair and few singers would have the courage to revisit such a hardline dressing down. Mick then finds himself playing Sisters of Mercy for the striking nurses and choking back tears so as to avoid a repeat of the asbestos song episode. He manages it but only just. My own eyes grew a bit misty reading this chapter. The idea of a singer at a strike meeting in these cynical times is itself moving!

So let’s throw another log on the equation. Those two albums appeared within six months of each other in the mid 1960s. Hoodoo Man Blues by Junior Wells was released at about the same time. Surely this knocks it out of Wrigley Field. Bloomfield and Clapton are great blues players but compared to Buddy Guy? Butterfield is one of the great harp players but, senator, he’s no Junior Wells. Case closed then. Well, maybe. Hoodoo Man Blues departs, quite dramatically at points, from the electric ‘country’ style associated with Muddy Waters, Wolf, and others. Listen to the first track, Snatch It Back and Hold It. It sounds a lot more like Papa’s got a Brand New Bag than Two Trains Running. Look over the track list. There’s a Kenny Burrell song on there! It’s a sophisticated and beautiful record but is it the blues? The ‘real’ blues?

So let’s throw another log on the equation. Those two albums appeared within six months of each other in the mid 1960s. Hoodoo Man Blues by Junior Wells was released at about the same time. Surely this knocks it out of Wrigley Field. Bloomfield and Clapton are great blues players but compared to Buddy Guy? Butterfield is one of the great harp players but, senator, he’s no Junior Wells. Case closed then. Well, maybe. Hoodoo Man Blues departs, quite dramatically at points, from the electric ‘country’ style associated with Muddy Waters, Wolf, and others. Listen to the first track, Snatch It Back and Hold It. It sounds a lot more like Papa’s got a Brand New Bag than Two Trains Running. Look over the track list. There’s a Kenny Burrell song on there! It’s a sophisticated and beautiful record but is it the blues? The ‘real’ blues?

There is a suggestion, raised a couple of times in the book, that the southern, Jim Crow Mississippi sources of the early Chicago sound are simply a different listening experience for black audiences. Possibly this is why the black audiences that have stuck with blues apparently favour the smoother, more urban sounds that white devotees of the genre, like me for instance, find dull and overproduced. So where does that leave us? What’s authentic now? The rough hewn sound of Muddy’s earlier sides or the slick lines of ZZ Hill, an artist credited with bringing blues back to its original audiences in the early 80s? Harper admits that he had never heard of ZZ Hill in 1982.

There is a suggestion, raised a couple of times in the book, that the southern, Jim Crow Mississippi sources of the early Chicago sound are simply a different listening experience for black audiences. Possibly this is why the black audiences that have stuck with blues apparently favour the smoother, more urban sounds that white devotees of the genre, like me for instance, find dull and overproduced. So where does that leave us? What’s authentic now? The rough hewn sound of Muddy’s earlier sides or the slick lines of ZZ Hill, an artist credited with bringing blues back to its original audiences in the early 80s? Harper admits that he had never heard of ZZ Hill in 1982.