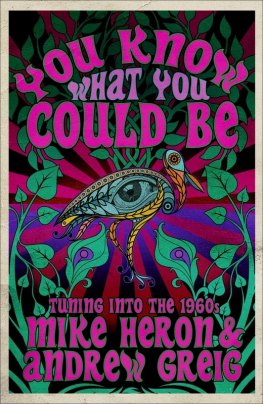

You Know What You Could Be: Tuning Into the 60s by Mike Heron and Andrew Greig, riverrun 2017

You Know What You Could Be: Tuning Into the 60s by Mike Heron and Andrew Greig, riverrun 2017

Mike Heron and Andrew Greig’s book, You Know What You Could Be: Tuning Into the 60s might appear from the cover to be a ghostwritten or co-written memoir of the former’s career. It isn’t, though it does include a lengthy section at the beginning by Mike Heron that recounts the early years of the band. The core of the book, however, is Andrew Greig’s own memoir of growing up in the late sixties with The Incredible String Band providing the soundtrack and a spiritual path.

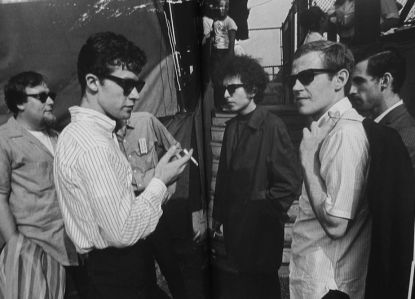

I was a bit perplexed by this format as I began the book. Mike Heron’s section is fascinating. His memories of the Scottish folk scene of the early sixties are vivid. Readers of Colin Harper’s Dazzling Stranger will already be aware that this period represents one of the great gatherings of talent and unique characters in popular music. Locals such as Bert Jansch, Alex Campbell (one of the drunken revelers in Dylan’s hotel room in Don’t Look Back -not the dude who threw the glass though), and Hamish Imlach mix with mythic figures like Anne Briggs in the legendary folk pubs of Edinburgh. At the semi rural home of Mary Stewart, the folk community mixes with the mountain climbing set. Rose Simpson, in fact, met Robin and Mike in the house after an unsuccessful attempt on Ben Nevis. Mary’s children appear on the cover of The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter, considered by many to be their finest album.

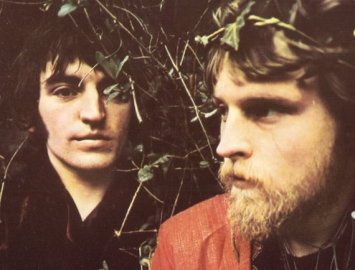

The first incarnation of ISB included Clive Palmer, another great British folk eccentric. He left after the first album and headed for Afghanistan before returning to the music world as a sort of cult musicians’ cult musician. If you’ve never heard Sunshine Possibilities by his Famous Jug Band or any of the early Clive’s Original Band (COB) records, the time has come! Mike Heron was an early fan who ended up playing with him in the trio that became The Incredible String Band. The story of their trip to London to record a demo for Elektra is wonderful and partially explains Clive’s plastic coat on the front of at least one version of the LP.

Clive Palmer (note jacket), Robin Williamson, Mike Heron

Just when I was getting ready to hear about the recording of my beloved The 5000 Spirits or the Layers of the Onion album and the time that Paul McCartney declared The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter the most important record of the year, the narrative came to an abrupt end.

Suddenly we’re back in Scotland in the mid sixties. It’s raining and Andrew Greig is at school. He discovers the Incredible String Band, has his mind blown, forms his own freak folk outfit, and becomes a poet. I enjoyed the stories but I kept waiting for Mike Heron to come back. Then the penny dropped.

Andrew Greig is not a rock journalist. He has written many books of poetry, a few novels, several books on mountain climbing, as well as a memoir about his friendship with the Scottish poet, Norman McCaig. He is a literary writer and thus his memories, musical and otherwise, of the 1960s are assuredly delivered. There is also a discernible subtext here and it relates to what is perhaps the most enduring legacy of The Incredible String Band. Andrew Greig heard the whisper of freedom in these endearingly loose records. The 1960s in Scotland was not, he observes, all that different from the 1940s. Men went to work, women stayed home and ironed sheets. Even Mike Heron’s father, the head of English at George Heriot’s School in Edinburgh, finds it hard to come to terms with Mike’s decision not to become a chartered accountant.

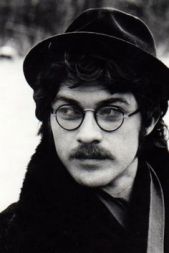

Fate & ferret (Andrew Greig, front right)

The Incredible String Band bring colour and light to the young Andrew’s dour existence in Fife. He and his friend George form a band called Fate & ferret. They write their own songs and go as far as meeting with Joe Boyd in London. Boyd is, of course, the John Hammond of English folk rock. His good taste brought, in addition to ISB, Sandy Denny, Nick Drake, John Martyn, Fairport Convention, and many others to the recording studio. In Greig’s memoir, he is friendly with them but not particularly interested in their music. Their initial meeting with him does lead to a gig opening for John Martyn at Les Cousins. Not bad for a high school band!

There are a number of books on The Incredible String Band that will provide a chronological account of their musical journey. Rob Young’s take on their career in Electric Eden is particularly good. But You Know What You Could Be is something different. Surely a band’s story must include their audience to some extent. Without going all ‘trees falling in the forest’ here, the effect of the music is often as significant as the music itself. Most rock and roll biographies will trace the influence of their subject on subsequent acts but what about the ordinary fans whose lives are changed, sometimes dramatically, by the music? Clearly, no one wants to read a whole book of Led Zeppelin fans cooing about Knebworth or, worse, a Deadhead memoir (there are many, if you do!) but I like what Greig has done in this book.

There are a number of books on The Incredible String Band that will provide a chronological account of their musical journey. Rob Young’s take on their career in Electric Eden is particularly good. But You Know What You Could Be is something different. Surely a band’s story must include their audience to some extent. Without going all ‘trees falling in the forest’ here, the effect of the music is often as significant as the music itself. Most rock and roll biographies will trace the influence of their subject on subsequent acts but what about the ordinary fans whose lives are changed, sometimes dramatically, by the music? Clearly, no one wants to read a whole book of Led Zeppelin fans cooing about Knebworth or, worse, a Deadhead memoir (there are many, if you do!) but I like what Greig has done in this book.

He has explained the real power of The Incredible String Band in a manner that wouldn’t be feasible in a straight biography. For most of us, our favourite bands exist in a dreamscape with a great soundtrack. We may see the band live or even meet the members but, as Yeats says, it is the dream itself that enchants us. You Know What You Could Be is a book about music, imagination, and the freedom to do exactly as you please. Who could ask for more?

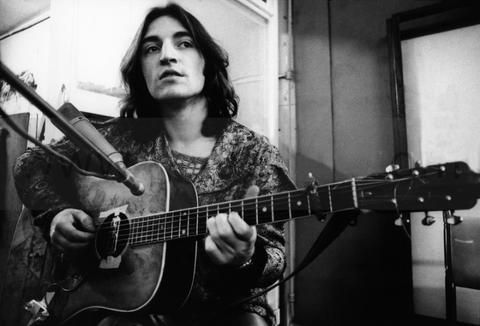

Mike Heron

(*The Band’s performance at Woodstock didn’t go over that well either. The Dead were booed apparently. No shame in struggling to identify the elusive zeitgeist of half a million wet hippies!)

Teasers: Wish you’d seen The Incredible String Band live in 1968? I sure do! Andrew Greig did and he has the writing chops to put you in the front row. I find many of the concerts I see these days far too formulaic. These chaotic evenings sound glorious!

Best song ever about insomnia!

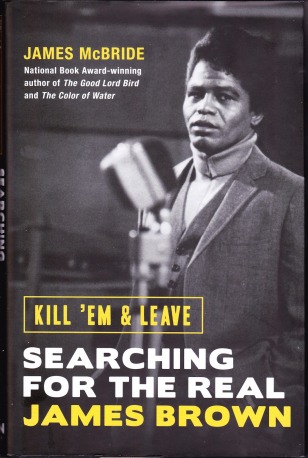

Kill ’Em And Leave: Searching for James Brown and the American Soul by James McBride, Spiegel & Grau 2016

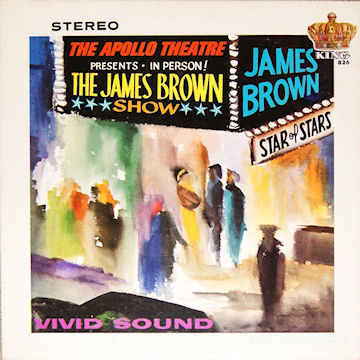

Kill ’Em And Leave: Searching for James Brown and the American Soul by James McBride, Spiegel & Grau 2016 I have only ever been a casual fan of James Brown. Like everyone else, I have owned Live at the Apollo in at least four formats, along with a greatest hits collection purchased during a brief teenage Mod phase. I saw him once too. In the mid 80s he played the Ontario Place Forum in Toronto with its revolving stage. It was a strange show. He did about five songs. Two of them were It’s A Man’s World. Then he came out with the cape, etc, for an encore. You guessed it, It’s A Man’s World one more time. I walked out of there like Robert Bly with a six-pack.

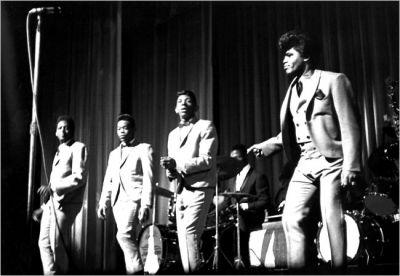

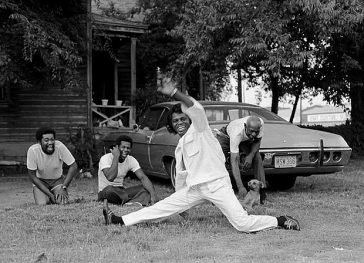

I have only ever been a casual fan of James Brown. Like everyone else, I have owned Live at the Apollo in at least four formats, along with a greatest hits collection purchased during a brief teenage Mod phase. I saw him once too. In the mid 80s he played the Ontario Place Forum in Toronto with its revolving stage. It was a strange show. He did about five songs. Two of them were It’s A Man’s World. Then he came out with the cape, etc, for an encore. You guessed it, It’s A Man’s World one more time. I walked out of there like Robert Bly with a six-pack. James McBride’s provocative account of Brown’s career makes one thing clear. The self styled Godfather of Soul does not fit easily into the received story of rock and roll. Motown makes sense. The Beatles drew from Motown. Chess makes sense. The Rolling Stones found something there. But James Brown’s legacy, in rock and roll at least, is less obvious. The story of his upstaging of the Stones is famous. Keith Richards has said that trying to follow him was the dumbest thing the band ever did. Brown, by some accounts, begat funk which begat disco. Okay, but we’re still talking about tributaries that exist outside of the rock and roll critical river. James McBride’s point here is never stated explicitly but his meaning is clear. James Brown is central to the African American experience of popular music. The standard Elvis – Beatles – Bowie – Punk – and so on story is arguably a very white one that, while not excluding black music, does sideline it. Elijah Wald explored this theme in his book How The Beatles Destroyed Rock and Roll a few years ago. James Brown’s story is certainly illustrative of it. If you’re shaking your head, think about this: The Beatles have appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone more than 30 times. James Brown, one of the key innovators in popular music, has appeared twice. The first time, in 1989, was well after his heyday and the second time, 2006, was after his death.

James McBride’s provocative account of Brown’s career makes one thing clear. The self styled Godfather of Soul does not fit easily into the received story of rock and roll. Motown makes sense. The Beatles drew from Motown. Chess makes sense. The Rolling Stones found something there. But James Brown’s legacy, in rock and roll at least, is less obvious. The story of his upstaging of the Stones is famous. Keith Richards has said that trying to follow him was the dumbest thing the band ever did. Brown, by some accounts, begat funk which begat disco. Okay, but we’re still talking about tributaries that exist outside of the rock and roll critical river. James McBride’s point here is never stated explicitly but his meaning is clear. James Brown is central to the African American experience of popular music. The standard Elvis – Beatles – Bowie – Punk – and so on story is arguably a very white one that, while not excluding black music, does sideline it. Elijah Wald explored this theme in his book How The Beatles Destroyed Rock and Roll a few years ago. James Brown’s story is certainly illustrative of it. If you’re shaking your head, think about this: The Beatles have appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone more than 30 times. James Brown, one of the key innovators in popular music, has appeared twice. The first time, in 1989, was well after his heyday and the second time, 2006, was after his death. McBride himself tasted literary stardom a few years ago with his memoir, The Color of Water. He is a formidable prose writer who has also worked as a professional musician. It’s not surprising that this book made so many ‘best of’ lists for 2016. As one era in the White House ends and we await the full implications of the one that will follow, McBride’s story of a man who scored his first hit in 1956 couldn’t be more relevant. The search for the soul of America is ongoing.

McBride himself tasted literary stardom a few years ago with his memoir, The Color of Water. He is a formidable prose writer who has also worked as a professional musician. It’s not surprising that this book made so many ‘best of’ lists for 2016. As one era in the White House ends and we await the full implications of the one that will follow, McBride’s story of a man who scored his first hit in 1956 couldn’t be more relevant. The search for the soul of America is ongoing. Testimony by Robbie Robertson, Deckle Edge 2016

Testimony by Robbie Robertson, Deckle Edge 2016

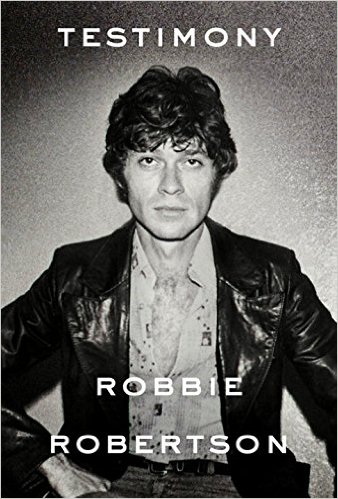

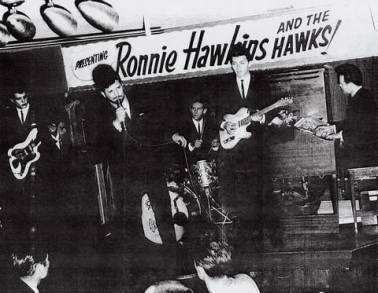

Robertson is particularly good on his early days with Ronnie Hawkins and the evolution of The Hawks. His growing friendship with Levon is at the heart of these sections but he also brings Hawkins, the sort of Dumbledore figure in The Band’s story, to life in all his manic glory. Slowly, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, and the arch eccentric, Garth Hudson of London Ontario, make their way into the Hawks. The band conquers Yonge St and all its young women. They play dives at Wasaga Beach, they play dives on the Mississippi. Robertson was 16 when he joined up. When The Band’s first album appeared in 1968, they had been on the road since the late 50s. The Beatles’ Hamburg period is, at least according to Malcolm Gladwell, an important factor in everything that followed. There is a special ingredient in The Band’s music that is sometimes hard to identify. Robbie’s wonderful evocation of the band’s early years provides an important clue, I believe. The threads of rockabilly, rhythm and blues, pop, blues, and a country ballad or two are all part of the fabric of The Band’s sound.

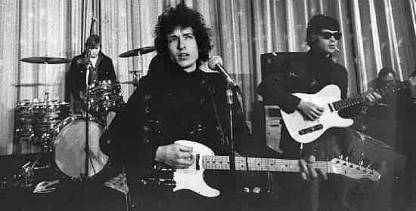

Robertson is particularly good on his early days with Ronnie Hawkins and the evolution of The Hawks. His growing friendship with Levon is at the heart of these sections but he also brings Hawkins, the sort of Dumbledore figure in The Band’s story, to life in all his manic glory. Slowly, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, and the arch eccentric, Garth Hudson of London Ontario, make their way into the Hawks. The band conquers Yonge St and all its young women. They play dives at Wasaga Beach, they play dives on the Mississippi. Robertson was 16 when he joined up. When The Band’s first album appeared in 1968, they had been on the road since the late 50s. The Beatles’ Hamburg period is, at least according to Malcolm Gladwell, an important factor in everything that followed. There is a special ingredient in The Band’s music that is sometimes hard to identify. Robbie’s wonderful evocation of the band’s early years provides an important clue, I believe. The threads of rockabilly, rhythm and blues, pop, blues, and a country ballad or two are all part of the fabric of The Band’s sound. Speaking of the Nobel Laureate, Robbie is very good on the 1966 tour. There has been so much written about it that I wondered if he would bother spending too much time there. He does and manages to provide a unique perspective. Dylan is one of a long series of ‘father figures’ in Robertson’s life. He never actually says this but Ronnie Hawkins gives way to Levon who gives way to Dylan who gives way to Albert Grossman who gives way to David Geffen who gives way to Martin Scorcese. Dylan’s intelligence and absolute cool headedness in every situation impresses the young guitarist as he ducks flying objects night after night on the ‘Judas’ tour.

Speaking of the Nobel Laureate, Robbie is very good on the 1966 tour. There has been so much written about it that I wondered if he would bother spending too much time there. He does and manages to provide a unique perspective. Dylan is one of a long series of ‘father figures’ in Robertson’s life. He never actually says this but Ronnie Hawkins gives way to Levon who gives way to Dylan who gives way to Albert Grossman who gives way to David Geffen who gives way to Martin Scorcese. Dylan’s intelligence and absolute cool headedness in every situation impresses the young guitarist as he ducks flying objects night after night on the ‘Judas’ tour. Following the section on the first album, the tone of Testimony shifts in a subtle way. Rick Danko manages to break his neck in a car accident before their first tour and Richard Manuel’s drinking starts to make an impact. Then Levon Helm discovers heroin. Robbie Robertson is a gentleman. He doesn’t scold or preach but the sense of a lost opportunity is discernible in the folds of his prose. I doubt that anyone will ever top this band’s first two albums but I think Robbie feels as though the records that followed could have been a lot better. He doesn’t think much of Cahoots, for instance. While it isn’t perhaps on par with its three predecessors, an album with Life is a Carnival, When I Paint My Masterpiece, and The River Hymn still must rank as one of the ten best albums of the 1970s.

Following the section on the first album, the tone of Testimony shifts in a subtle way. Rick Danko manages to break his neck in a car accident before their first tour and Richard Manuel’s drinking starts to make an impact. Then Levon Helm discovers heroin. Robbie Robertson is a gentleman. He doesn’t scold or preach but the sense of a lost opportunity is discernible in the folds of his prose. I doubt that anyone will ever top this band’s first two albums but I think Robbie feels as though the records that followed could have been a lot better. He doesn’t think much of Cahoots, for instance. While it isn’t perhaps on par with its three predecessors, an album with Life is a Carnival, When I Paint My Masterpiece, and The River Hymn still must rank as one of the ten best albums of the 1970s. This is something different, an unusual rock and roll memoir where the paucity of information functions as a kind of subtext. Robbie hasn’t come to terms with The Band and has perhaps been stung by his ‘Yoko-isation’ by fans and critics. I enjoyed Testimony enormously but this is perhaps a more melancholy book than the author intended.

This is something different, an unusual rock and roll memoir where the paucity of information functions as a kind of subtext. Robbie hasn’t come to terms with The Band and has perhaps been stung by his ‘Yoko-isation’ by fans and critics. I enjoyed Testimony enormously but this is perhaps a more melancholy book than the author intended. The Sun and The Moon and the Rolling Stones by Rich Cohen, Spiegel and Grau, 2016

The Sun and The Moon and the Rolling Stones by Rich Cohen, Spiegel and Grau, 2016 A book about The Rolling Stones presents something of a quandary to both writer and reader. What does one say about this band that isn’t already part of one of the great Rock and Roll myth cycles. The Stones were badass compared to The Beatles? The Sixties ended at Altamont during Under My Thumb? Exile on Main St was badly reviewed at the time (it really wasn’t – check for yourself) but is the greatest record ever made? There are almost as many books about the Stones as there are on The Beatles. This formidable library now includes Keith’s bestselling autobiography Life. Mick Jagger tells Cohen that Richards didn’t write it and probably hasn’t read it either. I wasn’t crazy about Life, to be honest, and this made me laugh out loud, as the kids say.

A book about The Rolling Stones presents something of a quandary to both writer and reader. What does one say about this band that isn’t already part of one of the great Rock and Roll myth cycles. The Stones were badass compared to The Beatles? The Sixties ended at Altamont during Under My Thumb? Exile on Main St was badly reviewed at the time (it really wasn’t – check for yourself) but is the greatest record ever made? There are almost as many books about the Stones as there are on The Beatles. This formidable library now includes Keith’s bestselling autobiography Life. Mick Jagger tells Cohen that Richards didn’t write it and probably hasn’t read it either. I wasn’t crazy about Life, to be honest, and this made me laugh out loud, as the kids say.

Heads: A Biography of Psychedelic America by Jesse Jarnow, Da Capo, 2016

Heads: A Biography of Psychedelic America by Jesse Jarnow, Da Capo, 2016 Narcotics were popular long before 1965. Nineteenth century Romanticism was fueled by opium, twentieth century Modernism ran on coke. Jean Paul Sartre took so much mescaline that he was having flashbacks involving talking lobsters for years. But in 1943, Albert Hoffman, a Swiss chemist, came up with something he called LSD. He took some, got on his bicycle, and rode, hopefully not in traffic, into history.

Narcotics were popular long before 1965. Nineteenth century Romanticism was fueled by opium, twentieth century Modernism ran on coke. Jean Paul Sartre took so much mescaline that he was having flashbacks involving talking lobsters for years. But in 1943, Albert Hoffman, a Swiss chemist, came up with something he called LSD. He took some, got on his bicycle, and rode, hopefully not in traffic, into history.

1966: The Year the Decade Exploded, Jon Savage, Faber and Faber 2015

1966: The Year the Decade Exploded, Jon Savage, Faber and Faber 2015 At the moment on my coffee table, there are books called 1607 (James Shapiro’s follow up to 1599), 1966, Detroit 67, and a novel by Garth Risk Hallberg called City on Fire which appears to be set entirely in 1977 although it’s 900 pages long and I’m only halfway through it. It might be 1979 when I finish. Or 2017. On my kobo, there is a book by David Browne called Fire and Rain that is all about 1970 and one from a few years ago called 1968 by Mark Kurlansky. They are all of interest but when ‘1996’ appears, don’t expect a review. I didn’t like anything about that whole decade.

At the moment on my coffee table, there are books called 1607 (James Shapiro’s follow up to 1599), 1966, Detroit 67, and a novel by Garth Risk Hallberg called City on Fire which appears to be set entirely in 1977 although it’s 900 pages long and I’m only halfway through it. It might be 1979 when I finish. Or 2017. On my kobo, there is a book by David Browne called Fire and Rain that is all about 1970 and one from a few years ago called 1968 by Mark Kurlansky. They are all of interest but when ‘1996’ appears, don’t expect a review. I didn’t like anything about that whole decade.

Some of these chapters are more convincing than others. His evocation of homosexuality in 1966 is particularly well done. The Tornados ‘Do you come here often?’, is widely thought of as the first ‘gay’ pop song – for those who missed the subtext of Tutti Frutti and countless other 1950s singles. Joe Meek, the legendary producer of this song, had begun his long slide into the madness that would end in his death in 1967. Like Brian Epstein, he led a secret life and had been subjected to arrest and blackmail attempts over the years. The laws were changing but it was still a difficult time to be gay in England. The chapter also picks up the story of San Francisco in that year. The Gay rights movement, in most people’s minds, begins with Stonewall in 1969 but Savage shows that it was already crystalising in 1966.

Some of these chapters are more convincing than others. His evocation of homosexuality in 1966 is particularly well done. The Tornados ‘Do you come here often?’, is widely thought of as the first ‘gay’ pop song – for those who missed the subtext of Tutti Frutti and countless other 1950s singles. Joe Meek, the legendary producer of this song, had begun his long slide into the madness that would end in his death in 1967. Like Brian Epstein, he led a secret life and had been subjected to arrest and blackmail attempts over the years. The laws were changing but it was still a difficult time to be gay in England. The chapter also picks up the story of San Francisco in that year. The Gay rights movement, in most people’s minds, begins with Stonewall in 1969 but Savage shows that it was already crystalising in 1966. ‘global village’ by 1966 and most of the events in the UK and US were mirrored in other places. Others may be able to point to music related events in Africa or even the Middle East. Please point!

‘global village’ by 1966 and most of the events in the UK and US were mirrored in other places. Others may be able to point to music related events in Africa or even the Middle East. Please point! Lives of the Poets (with Guitars): Thirteen Outsiders Who Changed Modern Music Ray Robertson, Biblioasis 2016

Lives of the Poets (with Guitars): Thirteen Outsiders Who Changed Modern Music Ray Robertson, Biblioasis 2016 Many novelists attempt this trick. Not many get there. Novels about rock and roll bands usually fall in a great big heap when the writer tries to describe the music. I’m happy to be corrected on this one. Please drench me in the names of credible rock and roll novels. I can think of three. The Doubleman is one, Paul Quarrington’s Whale Music is another. The final and greatest of all is Ray Robertson’s 2002 novel, Moody Food.

Many novelists attempt this trick. Not many get there. Novels about rock and roll bands usually fall in a great big heap when the writer tries to describe the music. I’m happy to be corrected on this one. Please drench me in the names of credible rock and roll novels. I can think of three. The Doubleman is one, Paul Quarrington’s Whale Music is another. The final and greatest of all is Ray Robertson’s 2002 novel, Moody Food. The first essay on Gene Clark sets the tone (and the volume, ha ha!). Clark is a notable cult figure. His album No Other can sit comfortably next to a whole bunch of other ambitious and brilliant albums that were completely ignored when they appeared. Clark’s sad tale is a staple of magazines like MOJO and Uncut but Ray tells it in such an affecting manner that it felt as though I was reading it for the first time. This musician’s musical journey was an unusual one that spanned several decades. Ray uses his considerable storytelling abilities to give his music a cohesive frame. This would be insupportable if the music wasn’t described with such clarity and detail. I could hear these albums as I read. That’s impressive.

The first essay on Gene Clark sets the tone (and the volume, ha ha!). Clark is a notable cult figure. His album No Other can sit comfortably next to a whole bunch of other ambitious and brilliant albums that were completely ignored when they appeared. Clark’s sad tale is a staple of magazines like MOJO and Uncut but Ray tells it in such an affecting manner that it felt as though I was reading it for the first time. This musician’s musical journey was an unusual one that spanned several decades. Ray uses his considerable storytelling abilities to give his music a cohesive frame. This would be insupportable if the music wasn’t described with such clarity and detail. I could hear these albums as I read. That’s impressive.

Detroit 67: The Year That Changed Soul Stuart Cosgrove, 2015

Detroit 67: The Year That Changed Soul Stuart Cosgrove, 2015 Detroit 67 begins with a long section outlining the day to day activities and troubled internal relations of The Supremes. The Motown gossip is here – yes, Berry Gordy was involved with Diana Ross – but the focus is on Florence Ballard who will, in Cosgrove’s account come to embody, not only the move by Motown Records towards a more corporate model, but also the decline of Detroit itself. The story then shifts rather abruptly to John Sinclair and the beginnings of the MC5. The connection, at first, seems tenuous. Sinclair hated Motown, though he had once shopped in Gordy’s unsuccessful record store for obscure jazz sides. The MC5 were about as far removed from The Supremes as would be possible in one city.

Detroit 67 begins with a long section outlining the day to day activities and troubled internal relations of The Supremes. The Motown gossip is here – yes, Berry Gordy was involved with Diana Ross – but the focus is on Florence Ballard who will, in Cosgrove’s account come to embody, not only the move by Motown Records towards a more corporate model, but also the decline of Detroit itself. The story then shifts rather abruptly to John Sinclair and the beginnings of the MC5. The connection, at first, seems tenuous. Sinclair hated Motown, though he had once shopped in Gordy’s unsuccessful record store for obscure jazz sides. The MC5 were about as far removed from The Supremes as would be possible in one city.

“It Takes Two” Diana Ross and Rob Tyner

“It Takes Two” Diana Ross and Rob Tyner

Small Town Talk by Barney Hoskyns, Da Capo Press 2016

Small Town Talk by Barney Hoskyns, Da Capo Press 2016

He thought that she was something truly special. And he was right! Anyone else noticed that Janis seems to be out of fashion at the moment? What’s that about?

He thought that she was something truly special. And he was right! Anyone else noticed that Janis seems to be out of fashion at the moment? What’s that about?