Diary of a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star by Ian Hunter, Omnibus 2019

Diary of a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star by Ian Hunter, Omnibus 2019

There is a problem with rock memoirs and it isn’t that most of them are windy ghostwritten doorstops put out for fast cash at Christmas time. No, the real issue is that they are all severely teleological. Readers of Keith Richards’ Life will have noticed that he doesn’t spend a lot of time on Their Satanic Majesties Request, beyond pronouncing it ‘a load of crap’. Exile on Main St gets pages and pages. Sticky Fingers seems to take up half the book. What’s the difference? Well, in retrospect, Exile and Sticky Fingers are two of the greatest records in popular music and high points for western civilization. Their Satanic Majesties Request, if not quite a load of crap, is a rare misstep in Keith’s long and glorious career. The narrative thus moves backwards. Keith Richards might tell the story chronologically but the emphasis is on what is considered valuable now.

“Load of crap,” says guitarist, NOW!

So what’s the alternative? If Mike Love had written at length about the MIU Album in his book – wait, he did, bad example! Okay, what if Robbie Robertson had given as much time to Islands as he did to Music From The Big Pink? That might have been interesting but would have seemed odd to all but the most devoted Band fans. The whole point of these memoirs is to explore those moments when the magic happened, not the ones in between.

So imagine a real time book by a major rock star written before rock and roll history had been Rolling Stoned, Mojo’d and Pitchforked into a series of ‘greatest of all time’ lists and canonical albums. Yes, imagine that, for a moment.

What if I told you that this book existed?

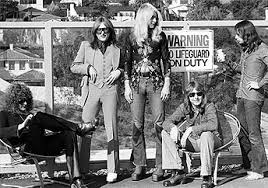

Ian Hunter’s Diary of a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star, first published in 1974, was written on a series of A4 note pages as his band, Mott The Hoople, toured the US at the end of 1972. Earlier that year, the hit single, All The Young Dudes, had revived a band on the verge of breaking up. Now they were hoping they could build an audience in the US. They might even get as big as Brownsville Station!

It is the painstaking detail of this book that builds the tension, and that tension is its power. It is filled with the minutiae of day-to-day tour life – taxi rides, flights, hotel rooms, soundchecks, shows, repeat. It doesn’t glamourize life on the road but it doesn’t go all gonzo either. Ian Hunter comes across as such a normal guy that more than a few times I had to remind myself that I was reading something written by a man I consider something of a genius. He is neither unusually virtuous nor deeply flawed. He loses his temper and makes plenty of dubious observations about women. But he also shows genuine concern for his band mates and the fans that approach him in every city. This is not a comic book version of rock and roll. There aren’t any epic nights of drug fueled bacchanalia or legendary scenes with multiple groupies. Instead, Hunter worries that he is gaining weight and wishes he didn’t always have to share a room with Verden Allen. He phones his wife, Trudy, every night and occasionally has too many beers.

It is the painstaking detail of this book that builds the tension, and that tension is its power. It is filled with the minutiae of day-to-day tour life – taxi rides, flights, hotel rooms, soundchecks, shows, repeat. It doesn’t glamourize life on the road but it doesn’t go all gonzo either. Ian Hunter comes across as such a normal guy that more than a few times I had to remind myself that I was reading something written by a man I consider something of a genius. He is neither unusually virtuous nor deeply flawed. He loses his temper and makes plenty of dubious observations about women. But he also shows genuine concern for his band mates and the fans that approach him in every city. This is not a comic book version of rock and roll. There aren’t any epic nights of drug fueled bacchanalia or legendary scenes with multiple groupies. Instead, Hunter worries that he is gaining weight and wishes he didn’t always have to share a room with Verden Allen. He phones his wife, Trudy, every night and occasionally has too many beers.

The gigs were chaotic. Mott The Hoople rarely seemed to be on top of the bill. Instead they shared shows with bands like It’s a Beautiful Day, Flash Cadillac, and New Riders of the Purple Sage. At one point, they have a dispute with Bloodrock about who will go on first and then end up not going on at all. In retrospect, it’s hard to imagine Ian Hunter considering them competition but that’s part of the charm of his account. Bloodrock were on the way up. It is 1972 as it was, rather than how we see it now. The ‘Mott’ album and his solo career were all still to come. Bands were coming and going all the time. All The Young Dudes is a rock solid classic song now but in 1972 it was just another single that was doing rather well. Nothing was guaranteed and, in this book, the reader gets an authentic glimpse of a rock and roll band working their tails off to hold their place at the table.

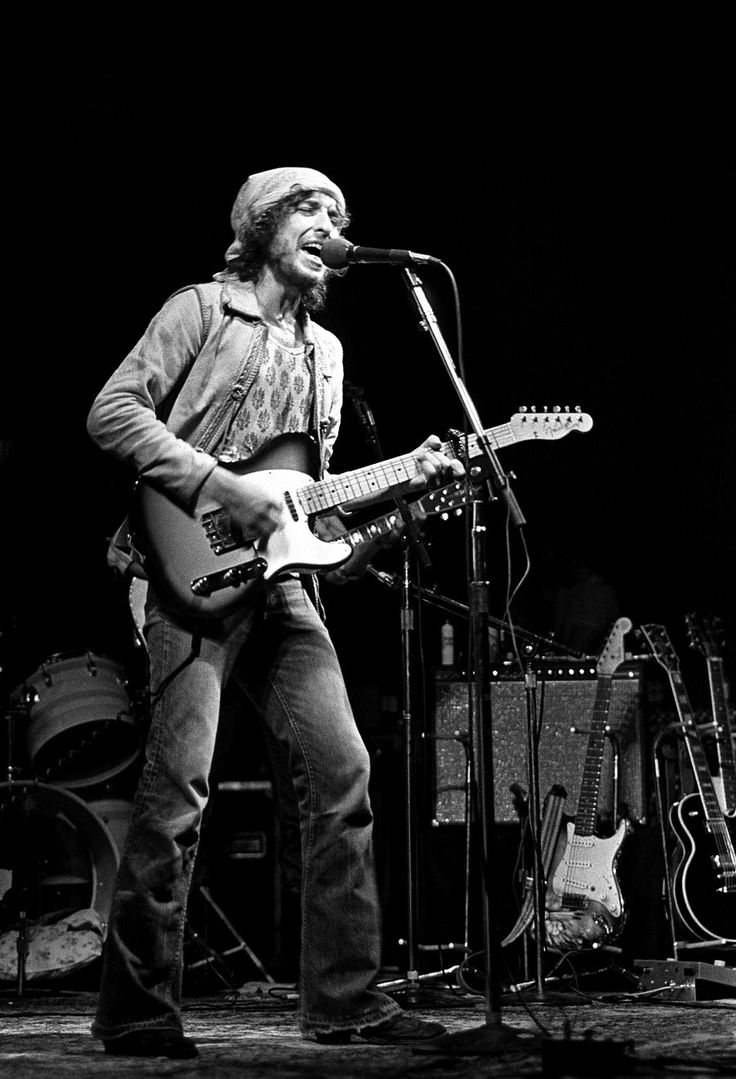

The most endearing passages are about what the band called ‘Shawn Pops’, their rhyming slang for pawn shops. In every city, they sought out these establishments to procure vintage American made guitars. Hunter makes the rather prophetic observation that these guitars are going to become extremely valuable as less expensive Japanese made instruments become more common. Little did he know that Nixon was in China around that time negotiating for even cheaper guitars! The pawn places were often in the dodgier parts of town and sometimes they had trouble convincing taxi drivers to take them. Once in the shops, they bargained with the grumpy owners and ended up with old Teles, 20 dollar Mosrites, and a slew of dirt cheap Gibson Juniors. The idea was to sell them at a profit back in England but you get the feeling that they kept most of them. I think you’ll read this book, if you haven’t already, so I won’t spoil the story of Hunter’s famous Maltese Cross guitar.

The most endearing passages are about what the band called ‘Shawn Pops’, their rhyming slang for pawn shops. In every city, they sought out these establishments to procure vintage American made guitars. Hunter makes the rather prophetic observation that these guitars are going to become extremely valuable as less expensive Japanese made instruments become more common. Little did he know that Nixon was in China around that time negotiating for even cheaper guitars! The pawn places were often in the dodgier parts of town and sometimes they had trouble convincing taxi drivers to take them. Once in the shops, they bargained with the grumpy owners and ended up with old Teles, 20 dollar Mosrites, and a slew of dirt cheap Gibson Juniors. The idea was to sell them at a profit back in England but you get the feeling that they kept most of them. I think you’ll read this book, if you haven’t already, so I won’t spoil the story of Hunter’s famous Maltese Cross guitar.

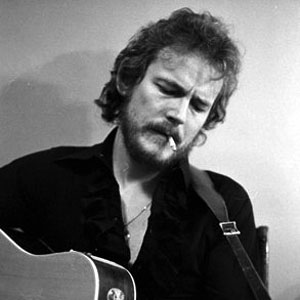

Mick Ralphs

Bowie makes a few cameo appearances as does Keith Moon but this is by no means a litany of ‘then I met…’ stories. The main characters in the book are the members of Mott, their manager Stan, and the people they meet in motels and backstage along the way. I was interested in the glimpses of Mick Ralphs, a loner according to Hunter, who was terrified of flying and seemed to suffer greatly throughout the tour. Ralphs soon left to form Bad Company but Hunter doesn’t dwell on whatever tensions were present in the classic line up of Mott. Again, there is nothing teleological here because obviously he had no idea what was going to happen next.

The reason I’m reviewing a book that appeared 45 years ago is that it has been reprinted, though not for the first time, and now includes some additional material to contextualize the original release and to give Johnny Depp an opportunity to pour love on Ian Hunter in the introduction. It is commonly considered one of the best books ever written about rock and roll but is not always easy to find in between printings. Grab it while you can and settle into your time machine. It’s a bumpy ride but like all great journeys, it ends with a party and a long flight back to England.

Teasers: Ian Hunter as critic. What does he think of Jethro Tull? What does he think of John McLaughlin? What about Zappa’s experimental tapes? And his favourite band of all time? Buy the book!

Metaphysical Graffiti: Rock’s Most Mind Bending Questions by Seth Kaufman, OR Books, 2019

Metaphysical Graffiti: Rock’s Most Mind Bending Questions by Seth Kaufman, OR Books, 2019

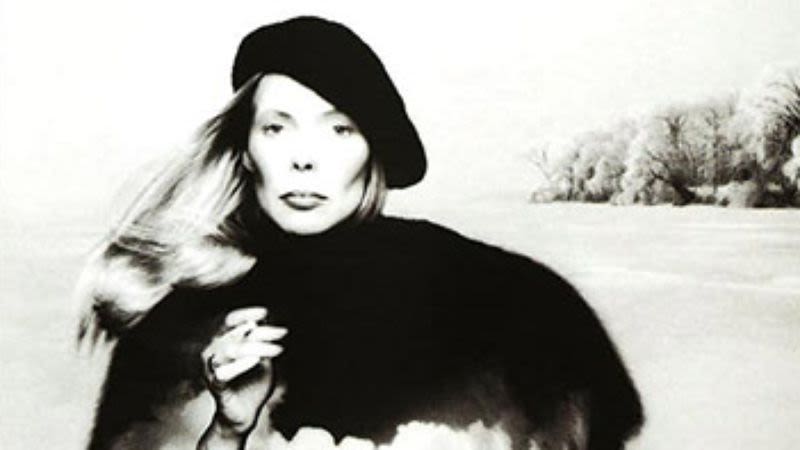

Kaufman thus goes old school by establishing some parameters for these discussions. The Billy Joel chapter is surprisingly interesting. He argues that ‘authenticity’ is a key part of the rock and roll story and that it might even represent an empirical notion (I’m ducking for cover now). He then tests songs like Only The Good Die Young against it. He’s as fair as anyone could be about this song but he determines that there is something fundamentally inauthentic about it. His son challenges him by bringing up The Carpenters as an analogous pop act. ‘Listen to Superstar’, Kaufman says. ‘It’s not her song but she absolutely fills it with her own pain.’ Billy’s pain in Only The Good Die Young, he points out, is more elusive. His writing seems to be missing a sense of what Heidegger called ‘Dasein’, a German word that translates as ‘being there’ or ‘presence’. There’s nobody home in his songs and that is a serious matter for a singer songwriter.

Kaufman thus goes old school by establishing some parameters for these discussions. The Billy Joel chapter is surprisingly interesting. He argues that ‘authenticity’ is a key part of the rock and roll story and that it might even represent an empirical notion (I’m ducking for cover now). He then tests songs like Only The Good Die Young against it. He’s as fair as anyone could be about this song but he determines that there is something fundamentally inauthentic about it. His son challenges him by bringing up The Carpenters as an analogous pop act. ‘Listen to Superstar’, Kaufman says. ‘It’s not her song but she absolutely fills it with her own pain.’ Billy’s pain in Only The Good Die Young, he points out, is more elusive. His writing seems to be missing a sense of what Heidegger called ‘Dasein’, a German word that translates as ‘being there’ or ‘presence’. There’s nobody home in his songs and that is a serious matter for a singer songwriter. Kaufman avoids sounding like Simon Frith by keeping the tone of the discussions humorous and often self-deprecating. His experience as a ‘recovering’ Deadhead will resonate with anyone who has flirted with this band over the years. Ann Coulter’s identity as a deadhead and her contention that the band has a considerable alt right following has presented the faithful with some difficult questions. Kaufman rightly points out that Coulter is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to Grateful Dead paradoxes. “Would it still be a Dead concert if the Deadheads didn’t turn up?” he asks. If I ever teach philosophy again, that is going to be on the exam!

Kaufman avoids sounding like Simon Frith by keeping the tone of the discussions humorous and often self-deprecating. His experience as a ‘recovering’ Deadhead will resonate with anyone who has flirted with this band over the years. Ann Coulter’s identity as a deadhead and her contention that the band has a considerable alt right following has presented the faithful with some difficult questions. Kaufman rightly points out that Coulter is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to Grateful Dead paradoxes. “Would it still be a Dead concert if the Deadheads didn’t turn up?” he asks. If I ever teach philosophy again, that is going to be on the exam!

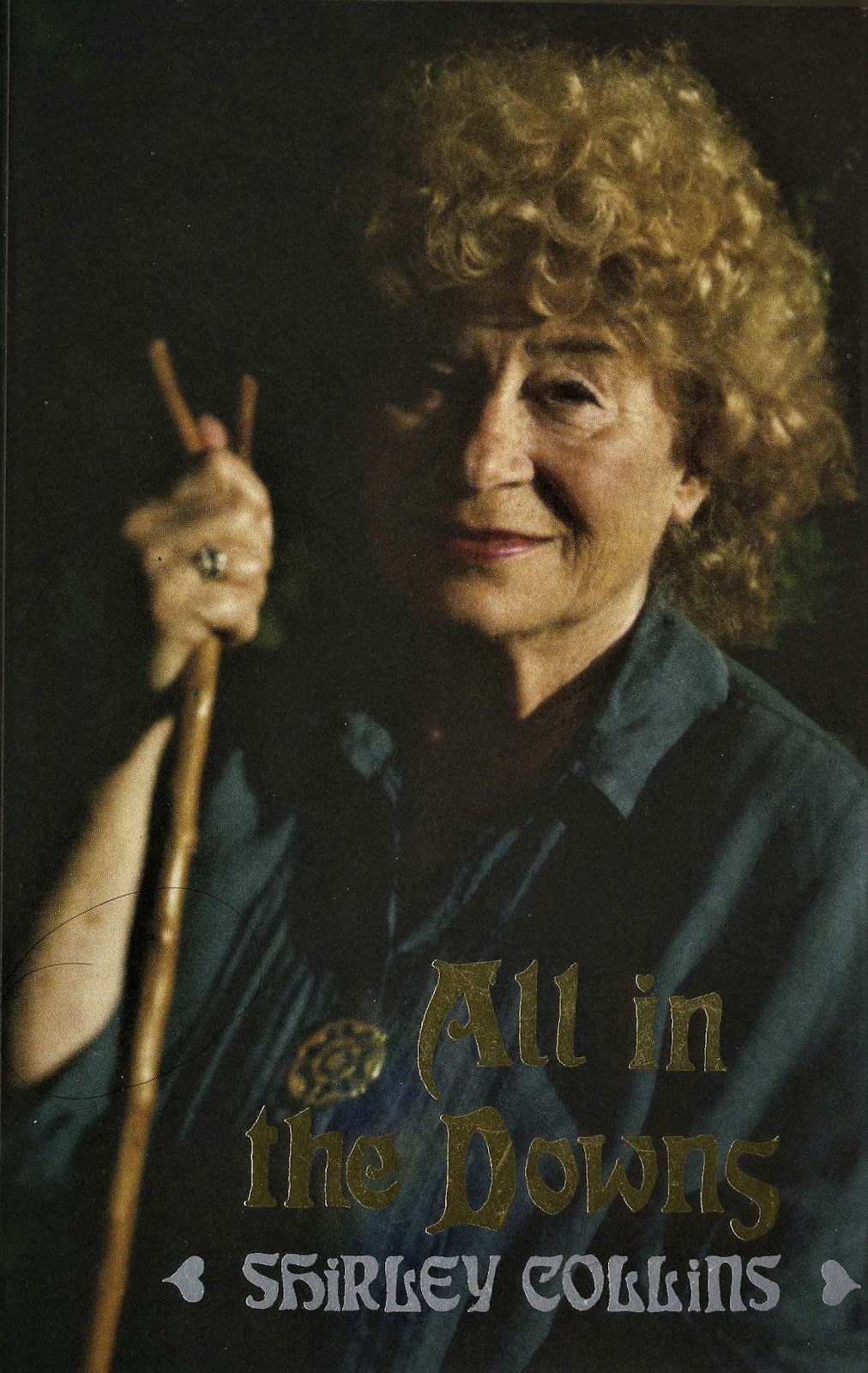

All in the Downs by Shirley Collins, Strange Attractor Press, 2018

All in the Downs by Shirley Collins, Strange Attractor Press, 2018

But let’s talk about ‘No Roses’, the greatest album Fairport Convention never made. Except that they sort of did. Most of the ‘Liege and Lief’ era members (only Sandy and Swarbs don’t appear) turn up somewhere on this 1971 album. I’m not going to suggest that it is the equal of that record but if you love ‘Liege and Lief’ and are frustrated by all of the Fairport albums that followed, I might be your new best pal for suggesting this one, if you’ve never heard it. Richard Thompson, Simon Nicol, Ashley Hutchings (it was his group, the Albion Country Band backing her), and Dave Mattacks all appear on the record, along with members of the Young Tradition, Maddy Pryor, sister Dolly, Lal and Mike Waterson, and the awesome Nic Jones. I found out about this record reading Electric Eden and it has become a great favourite.

But let’s talk about ‘No Roses’, the greatest album Fairport Convention never made. Except that they sort of did. Most of the ‘Liege and Lief’ era members (only Sandy and Swarbs don’t appear) turn up somewhere on this 1971 album. I’m not going to suggest that it is the equal of that record but if you love ‘Liege and Lief’ and are frustrated by all of the Fairport albums that followed, I might be your new best pal for suggesting this one, if you’ve never heard it. Richard Thompson, Simon Nicol, Ashley Hutchings (it was his group, the Albion Country Band backing her), and Dave Mattacks all appear on the record, along with members of the Young Tradition, Maddy Pryor, sister Dolly, Lal and Mike Waterson, and the awesome Nic Jones. I found out about this record reading Electric Eden and it has become a great favourite.

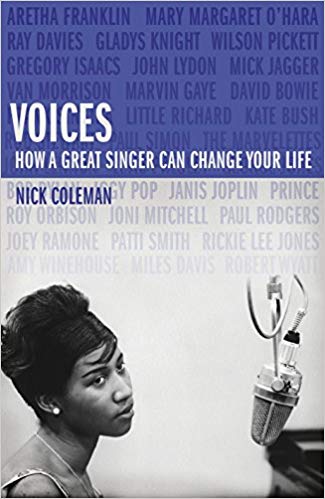

Voices: How a Singer Can Change Your Life by Nick Coleman, Jonathan Cape 2018

Voices: How a Singer Can Change Your Life by Nick Coleman, Jonathan Cape 2018

Woman* Walk The Line: How the Women in Country Music Changed Our Lives by Holly Gleason (editor), University of Texas Press 2017

Woman* Walk The Line: How the Women in Country Music Changed Our Lives by Holly Gleason (editor), University of Texas Press 2017

Memphis ’68: The Tragedy of Southern Soul by Stuart Cosgrove, Polygon, 2017

Memphis ’68: The Tragedy of Southern Soul by Stuart Cosgrove, Polygon, 2017

Memphis Rent Party: The Blues, Rock & Soul in Music’s Hometown by Robert Gordon

Memphis Rent Party: The Blues, Rock & Soul in Music’s Hometown by Robert Gordon But most of the pieces here deal with Memphis musicians. James Carr, a soul great that has never had anywhere near the recognition he deserves, is profiled. His story is another sad one. He recorded the original, and by far the best, version of Dan Penn’s Dark End of the Street on Goldwax Records in 1967. It should have set him up for a lifetime’s career in music. Instead, he battled terrible mental health problems and substance abuse issues until his death in 2001. Gordon’s interview presents him with the almost Lear-like pathos of a delicate soul unraveling. This is something of a pattern in these essays. The brilliant Jazz pianist Phineas Newborn Jr suffered numerous nervous breakdowns after his initial success in the late 50s and even had his fingers broken in a bar one night. Gordon interviews his mother here and profiles his brother Calvin. Jerry McGill, a Sun Records recording artist and the subject of one of Gordon’s films, is another hard luck story albeit one with a mildly happy ending.

But most of the pieces here deal with Memphis musicians. James Carr, a soul great that has never had anywhere near the recognition he deserves, is profiled. His story is another sad one. He recorded the original, and by far the best, version of Dan Penn’s Dark End of the Street on Goldwax Records in 1967. It should have set him up for a lifetime’s career in music. Instead, he battled terrible mental health problems and substance abuse issues until his death in 2001. Gordon’s interview presents him with the almost Lear-like pathos of a delicate soul unraveling. This is something of a pattern in these essays. The brilliant Jazz pianist Phineas Newborn Jr suffered numerous nervous breakdowns after his initial success in the late 50s and even had his fingers broken in a bar one night. Gordon interviews his mother here and profiles his brother Calvin. Jerry McGill, a Sun Records recording artist and the subject of one of Gordon’s films, is another hard luck story albeit one with a mildly happy ending.

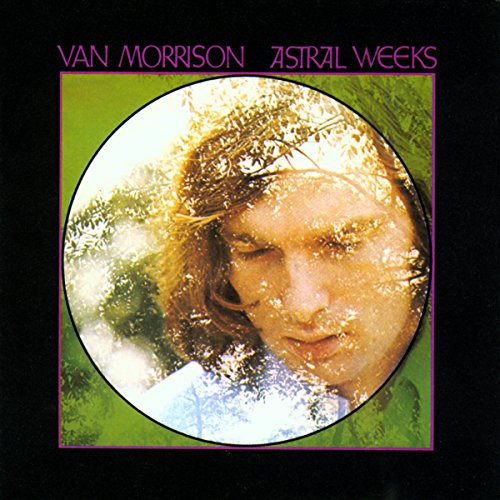

Astral Weeks: A Secret History of 1968 by Ryan Walsh, Penguin 2018

Astral Weeks: A Secret History of 1968 by Ryan Walsh, Penguin 2018

Walsh points out that Boston already had some form in the occult game. The city had been a hotbed of spooky fun during the great age of American spiritualism in the late 19th Century. The Fox Sisters opened a branch of their New York operation there in the 1870s. According to Walsh, one of their first customers was former first lady, Mary Todd Lincoln. She had already visited pioneering ‘spirit photographer’, William Mumler over on Washington Street for a photo of her with Abe’s ghost. The Boston Planchette, a prototype of the Ouija board, appeared in the 1860s. Walsh makes an interesting, if somewhat tenuous, connection between the spiritualist Edgar Cayce and the rise of the progressive ‘free form’ FM format on the legendary WCBN. Radios appear throughout Van’s lyrics and they often have a slightly mystical resonance. Watch the clip of Caravan from The Last Waltz where he begins to riff on the idea of The Band as a radio. Walsh doesn’t suggest there is a direct link – there is a significant and much earlier radio in 1967’s TB Sheets – but late night FM was an important part of Van’s life in Boston and radio seems to have been imbued with a certain spiritualist quality in that city.

Walsh points out that Boston already had some form in the occult game. The city had been a hotbed of spooky fun during the great age of American spiritualism in the late 19th Century. The Fox Sisters opened a branch of their New York operation there in the 1870s. According to Walsh, one of their first customers was former first lady, Mary Todd Lincoln. She had already visited pioneering ‘spirit photographer’, William Mumler over on Washington Street for a photo of her with Abe’s ghost. The Boston Planchette, a prototype of the Ouija board, appeared in the 1860s. Walsh makes an interesting, if somewhat tenuous, connection between the spiritualist Edgar Cayce and the rise of the progressive ‘free form’ FM format on the legendary WCBN. Radios appear throughout Van’s lyrics and they often have a slightly mystical resonance. Watch the clip of Caravan from The Last Waltz where he begins to riff on the idea of The Band as a radio. Walsh doesn’t suggest there is a direct link – there is a significant and much earlier radio in 1967’s TB Sheets – but late night FM was an important part of Van’s life in Boston and radio seems to have been imbued with a certain spiritualist quality in that city.

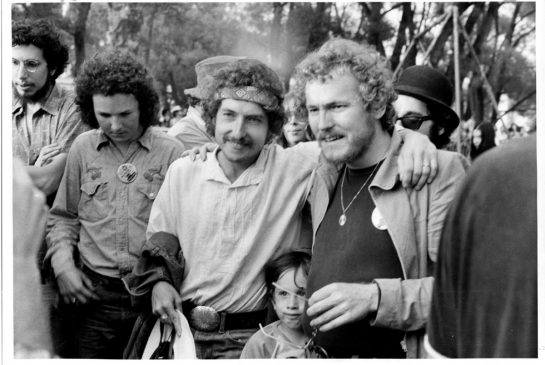

Walsh builds his book around a search. He’d heard that Peter Wolf (of the J. Geils Band) had a reel-to-reel tape of a performance by Van Morrison from the summer of 1968. The show was at a venue called The Catacombs and it featured Van on acoustic guitar backed by his bass player, Tom Keilbania, and John Payne who later played flute on Astral Weeks. The rumour is that the tape contained early performances of the songs on that album along with things like Moondance and Domino. The story has always been that Berliner and Davies were more or less improvising in the recording sessions for Astral Weeks. Keilbania has maintained that the ideas on the record were developed during the summer of 68 in the gigs they played in Boston. Critics are always banging on about rosetta stones in rock and roll but this would be the real deal. So what happens? Does Walsh find the recording? You’ll have to read for yourself. No spoilers here but don’t bother hitting up your favourite source of bootlegs. It aint there. Yet…

Walsh builds his book around a search. He’d heard that Peter Wolf (of the J. Geils Band) had a reel-to-reel tape of a performance by Van Morrison from the summer of 1968. The show was at a venue called The Catacombs and it featured Van on acoustic guitar backed by his bass player, Tom Keilbania, and John Payne who later played flute on Astral Weeks. The rumour is that the tape contained early performances of the songs on that album along with things like Moondance and Domino. The story has always been that Berliner and Davies were more or less improvising in the recording sessions for Astral Weeks. Keilbania has maintained that the ideas on the record were developed during the summer of 68 in the gigs they played in Boston. Critics are always banging on about rosetta stones in rock and roll but this would be the real deal. So what happens? Does Walsh find the recording? You’ll have to read for yourself. No spoilers here but don’t bother hitting up your favourite source of bootlegs. It aint there. Yet…

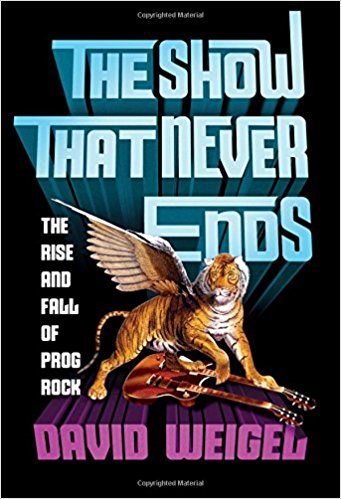

The Show That Never Ends: The Rise and Fall of Prog Rock by David Weigel, WW Norton & Co, 2016

The Show That Never Ends: The Rise and Fall of Prog Rock by David Weigel, WW Norton & Co, 2016 Weigel manages to produce a serious history of Prog without turning it into Das Kapital. He is a big fan but he also understands that there is something innately funny about the genre. Pomposity was one of its hallmarks in the manner that nihilistic aggression was part of punk. That is to say, it was pompous but unapologetically so. Naturally, Prog became something of a punchline. This was, after all a genre where one band (Magma) made up its own language (Kobaian). Rock critics hated it. They took the first few albums on their own merits – Lester Bangs liked Yes’s first album, for example – but shot each subsequent release down like wooden ducks on the midway. Remember that these writers, for the most part, found Led Zeppelin pretentious. Imagine what they thought when Rick Wakeman’s The Six Wives of Henry VIII turned up for review. When Emerson Lake and Palmer released Trilogy in 1972, Robert Christgau wrote: “The pomposities of Tarkus and the monstrosities of the Mussorgsky homage clinch it–these guys are as stupid as their most pretentious fans. Really, anybody who buys a record that divides a composition called “The Endless Enigma” into two discrete parts deserves it.” Still, for a little while, Prog went over like horses with the record buying and concert attending public. The most popular band of today wouldn’t dare to dream of selling a tenth of what a lesser Kansas record would have in the 70s.

Weigel manages to produce a serious history of Prog without turning it into Das Kapital. He is a big fan but he also understands that there is something innately funny about the genre. Pomposity was one of its hallmarks in the manner that nihilistic aggression was part of punk. That is to say, it was pompous but unapologetically so. Naturally, Prog became something of a punchline. This was, after all a genre where one band (Magma) made up its own language (Kobaian). Rock critics hated it. They took the first few albums on their own merits – Lester Bangs liked Yes’s first album, for example – but shot each subsequent release down like wooden ducks on the midway. Remember that these writers, for the most part, found Led Zeppelin pretentious. Imagine what they thought when Rick Wakeman’s The Six Wives of Henry VIII turned up for review. When Emerson Lake and Palmer released Trilogy in 1972, Robert Christgau wrote: “The pomposities of Tarkus and the monstrosities of the Mussorgsky homage clinch it–these guys are as stupid as their most pretentious fans. Really, anybody who buys a record that divides a composition called “The Endless Enigma” into two discrete parts deserves it.” Still, for a little while, Prog went over like horses with the record buying and concert attending public. The most popular band of today wouldn’t dare to dream of selling a tenth of what a lesser Kansas record would have in the 70s.

The next big challenge is finding a starting point. Weigel begins with The Moody Blues, Procol Harum, The Nice, and Pink Floyd. He mentions The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper which I think may have given permission for some of the high concept psychedelia that followed. The Who’s Tommy, The Small Faces’ Odgen’s Nut Gone Flake, and The Zombies’ Odessey and Oracle come to mind. I was surprised that The Pretty Things’ SF Sorrow didn’t rate a mention. Weigel more or less settles on The Moody Blues’ Days of Future Passed and King Crimson’s In the Court of the Crimson King as the point of lift off. Naturally, some of the other bands had false starts. The first Genesis album is a lot closer to Cucumber Castle than most Prog fans would care to admit. Just over two years later, they recorded Supper’s Ready, a 23 minute masterpiece or nightmare, depending on your perspective. Either way, it is Prog’s answer to The Wasteland. How’s that for a big call?

The next big challenge is finding a starting point. Weigel begins with The Moody Blues, Procol Harum, The Nice, and Pink Floyd. He mentions The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper which I think may have given permission for some of the high concept psychedelia that followed. The Who’s Tommy, The Small Faces’ Odgen’s Nut Gone Flake, and The Zombies’ Odessey and Oracle come to mind. I was surprised that The Pretty Things’ SF Sorrow didn’t rate a mention. Weigel more or less settles on The Moody Blues’ Days of Future Passed and King Crimson’s In the Court of the Crimson King as the point of lift off. Naturally, some of the other bands had false starts. The first Genesis album is a lot closer to Cucumber Castle than most Prog fans would care to admit. Just over two years later, they recorded Supper’s Ready, a 23 minute masterpiece or nightmare, depending on your perspective. Either way, it is Prog’s answer to The Wasteland. How’s that for a big call?

I must admit that, Pink Floyd and Jethro Tull aside, I have never been a great fan of this stuff. While reading the book, however, I discovered some wonderful King Crimson albums I’d never heard and finally picked up Robert Wyatt’s Rock Bottom. I even spun Emerson Lake and Palmer’s first record one night. Lucky Man brought back good memories of summer camp in the 1970s. I was struck by a sense that this music was more a part of my childhood than I thought. However, Gabriel-era Genesis remains too freaky for me. I have a complicated and slightly scary story about why I don’t listen to them but I’ll save that for when Peter Gabriel writes a memoir.

I must admit that, Pink Floyd and Jethro Tull aside, I have never been a great fan of this stuff. While reading the book, however, I discovered some wonderful King Crimson albums I’d never heard and finally picked up Robert Wyatt’s Rock Bottom. I even spun Emerson Lake and Palmer’s first record one night. Lucky Man brought back good memories of summer camp in the 1970s. I was struck by a sense that this music was more a part of my childhood than I thought. However, Gabriel-era Genesis remains too freaky for me. I have a complicated and slightly scary story about why I don’t listen to them but I’ll save that for when Peter Gabriel writes a memoir.

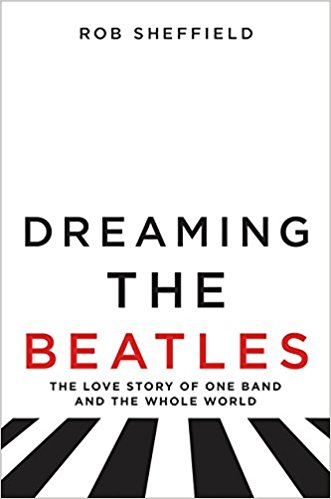

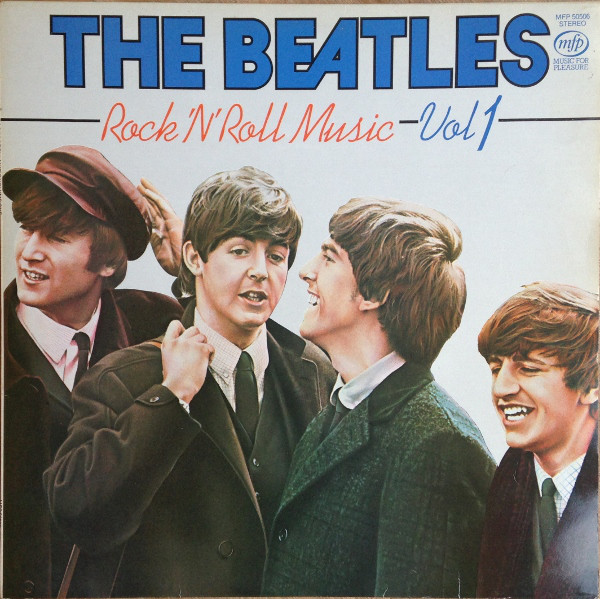

Dreaming The Beatles by Rob Sheffield, Harper Collins, 2017

Dreaming The Beatles by Rob Sheffield, Harper Collins, 2017

One of the threads holding the book together is a series of reflections on the relationship between John and Paul. The chapter with the best title, Paul Is A Concept By Which We Measure Our Pain, is a heartfelt essay on the John/Paul dynamic and its wider implications. “Every drama queen John needs a Paul to sweep up after him. It’s tough for two Johns to be friends, which is why Johns find themselves entangled with Pauls who disappoint them.” Wow. The Beatles as a model for Transactional Analysis. Sheffield says, movingly: “For John, Paul was the boy who came to stay; for Paul, John was the sad song he couldn’t make better.” They couldn’t escape each other. In 1975, John said, “If I took up ballet dancing, my ballet dancing would be compared with Paul’s bowling.” The obvious Fred Flintstone reference aside, he was spot on and Paul’s bowling is still being compared to John’s dancing.

One of the threads holding the book together is a series of reflections on the relationship between John and Paul. The chapter with the best title, Paul Is A Concept By Which We Measure Our Pain, is a heartfelt essay on the John/Paul dynamic and its wider implications. “Every drama queen John needs a Paul to sweep up after him. It’s tough for two Johns to be friends, which is why Johns find themselves entangled with Pauls who disappoint them.” Wow. The Beatles as a model for Transactional Analysis. Sheffield says, movingly: “For John, Paul was the boy who came to stay; for Paul, John was the sad song he couldn’t make better.” They couldn’t escape each other. In 1975, John said, “If I took up ballet dancing, my ballet dancing would be compared with Paul’s bowling.” The obvious Fred Flintstone reference aside, he was spot on and Paul’s bowling is still being compared to John’s dancing.

When I was 17, my dad introduced me to his new girlfriend, a woman called Anne. She was in her 40s and was in the habit of punctuating everything she said with one of those smoker’s laughs that sound like a cough. When my dad went into another room to take a phone call, she asked if it was true that I liked music. I said it was. She told me that ‘Gordy’ Lightfoot had written a song about her. Really, I said, which one? Sundown, she told me. Isn’t that about a prostitute? I asked. When my dad returned, Anne said, ‘I think your son just called me a hooker.’ It was awkward.

When I was 17, my dad introduced me to his new girlfriend, a woman called Anne. She was in her 40s and was in the habit of punctuating everything she said with one of those smoker’s laughs that sound like a cough. When my dad went into another room to take a phone call, she asked if it was true that I liked music. I said it was. She told me that ‘Gordy’ Lightfoot had written a song about her. Really, I said, which one? Sundown, she told me. Isn’t that about a prostitute? I asked. When my dad returned, Anne said, ‘I think your son just called me a hooker.’ It was awkward. Where I come from, Gordon Lightfoot is bigger than…well, just about anyone. Put it this way, a lot of Canadians who wouldn’t know a Neil Young song if one backed over them could probably easily name 10 Lightfoot songs. I remember my grandfather throwing Gord’s Gold into the 8 track player and letting it play over and over all day. I can also remember the Canadian bands I loved in the 1980s name checking him in interviews and playing his songs in encores. He played Massey Hall every year to audiences that included Bay Street lawyers, Scarborough tow truck drivers, hippies, punks, Social Studies teachers, and glad handing politicians. He could have run for Parliament, he could have been crowned king.

Where I come from, Gordon Lightfoot is bigger than…well, just about anyone. Put it this way, a lot of Canadians who wouldn’t know a Neil Young song if one backed over them could probably easily name 10 Lightfoot songs. I remember my grandfather throwing Gord’s Gold into the 8 track player and letting it play over and over all day. I can also remember the Canadian bands I loved in the 1980s name checking him in interviews and playing his songs in encores. He played Massey Hall every year to audiences that included Bay Street lawyers, Scarborough tow truck drivers, hippies, punks, Social Studies teachers, and glad handing politicians. He could have run for Parliament, he could have been crowned king.

Jennings explores Lightfoot’s relationship with Bob Dylan in some detail. Dylan is a fan, no question. There is a small group of songwriters that Dylan admires. He is generous but fickle on this topic in interviews. Sometimes he mentions John Prine, sometimes it’s Jimmy Buffett (no, really, he said that once) but the name that consistently comes up is Gordon Lightfoot.

Jennings explores Lightfoot’s relationship with Bob Dylan in some detail. Dylan is a fan, no question. There is a small group of songwriters that Dylan admires. He is generous but fickle on this topic in interviews. Sometimes he mentions John Prine, sometimes it’s Jimmy Buffett (no, really, he said that once) but the name that consistently comes up is Gordon Lightfoot.